A Sapling, Plain and Vigorous

A Sunday with the North Country Mennonites

To a pilot the region might seem like a quilt, patched as it is with alluvial fields and stands of Pinus Strobus — the glorious white pine. The gentle grades of Franklin County wander here, taking the motorist down into gulches of winter-dead poke and bramble by steel-grate bridges and then lifting him without fanfare up just far enough to enjoy commanding views of the area's northerly neighbor — Quebec.

Chatting by the horse-stables, I saw the black-clad men all smile when I offered my commentary on the real estate market here. One says:

"It sure is cheap —"

But haltingly the men cease to comment further on the matter lest they might be taken as being boastful of their spoils in this sleeping kingdom of dirt-cheap loam and tilth. And along the pot-holed truck trail leading to the Old Order Mennonite church, there are few trucks — instead, a trail of horse-drawn buggies glide in unison across the iced-over ruts of the sandy road like so many chariots on the road to Damascus.

This is Brushton — a settlement named, ostensibly, for its endless chasms of brush. If one wishes to lay down in an easy place, Brushton would be low on his list; for summer sun-tanning days are counted on two hands in this region, and a good few residents of the area are far too modest to tan more than their wrists and weathered noses whenever the sun does decide to show up. These are the Mennonites — the stolid and quiet adherents of a peaceful and genteel sect of Anabaptists. Beardless and clad in black, they ride buggies that are markedly different from those of their Amish neighbors. While the bearded Amish men push down the road in narrow, tightly angled contraptions that jolt over every pothole (for lack of suspension) the clean-shaven Mennonites glide regally in their big black boxes with windows, padded by springs beneath their seats, their horses dressed in tackle that seems to glisten in the sun — tackle that seems as if it could cause a scandal in any old-school Amish enclave.

Yet scandal seems impossible when interfacing with these men; they are jocular and cheerful, constantly possessed of broad, earnest smiles — hardly strangers to chuckling banter and yet effortlessly able to keep every word uttered completely wholesome. Last Sunday I rode up to their church in my own buggy — a Honda Odyssey — with my beloved, Keturah, who spent some years living with the Amish as a teenager. Old German, Anabaptism, and the politics of which sects can and cannot wear polka dot dresses are nothing strange to her, and so as we approached the big, barnlike church she suggested I speak to the men standing by their horses.

As I sidled up to them I was nervous; insofar as I could ever tell, there was a 'line' between the Anabaptists and 'the English' (as they call us); a line that seemed sociologically impossible for either side to breach except as it relates to business. Nevertheless I approached — on spiritual business. Their church service had just let out. We'd missed it, as we'd been busy attending the services of the church these Mennonites' forefathers had split off from in the 16th century — a mass of the Roman Catholic Church. The drama of this schism was hardly palpable on this sunny Sunday, however, as the men greeted me with the utmost politeness and cheer. One of them was, it turned out, the minister — he greeted me as if I were an old friend.

Thick accents poured out of the wizened faces shaded by broad-brimmed black caps. As if I had stumbled into a psychedelic cornfield dress rehearsal of a bizarre historical re-enactment film, these stern-looking fellows chortled at me in an implaceable foreign patois.

"Yeh kin comme to the service any Sundy, yes, 'an if yeh should come a bit early, we'll preach in the English for yer sake."

Their words were formal, kind, genteel, musical; the phrase "peace to men of good will" seemed to ring with perfect clarity in the company of these antiquarian gentlemen — these were the quintessential men of good will.

And so a week later, Keturah and I would again pass over the rutted, icy road to the Mennonite outpost in Brushton for an experience that felt not a whit different from travel to a foreign country — or perhaps even time travel. Upon being receieved by a Mennonite man and gently told that the women and men sit on different sides of the church, Keturah headed over to her station while I somewhat awkwardly made my slow entrance into the mens' side of the building. As I crossed the threshold into the sanctuary, a gauntlet of jacketed men and boys all stood guard — dozens of them, all crammed into the corridor, each holding his hat against his midsection. Yet my entrance was not that of an Admiral — many of them seemed not to know what to do with an 'English' like me; they shook hands with the Mennonite men who both preceded and followed me in the entrance line, but to me a number of them only gave confused looks. A couple of them seemed to understand what this experience might be like for me and, with a quick look of sympathy, they reached their hands out for a brisk handshake and a word of welcome.

I had no idea where to sit. A man guided me to the hat-rack; luckily I'd chosen to wear my grandfather's old Australian outback hat — a broad-brimmed number of brown felt. It was nearly within the guidelines of the other Mennonite men's hats, and yet it stood out sorely on the rack. Then a man silently pointed to a spot in the pews, close to the pulpit — this was to become my new home for the next three hours.

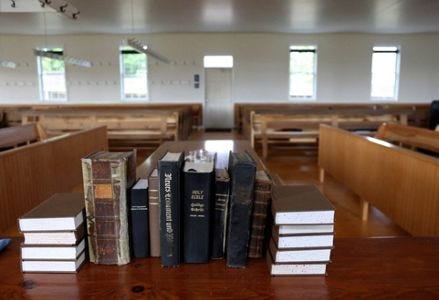

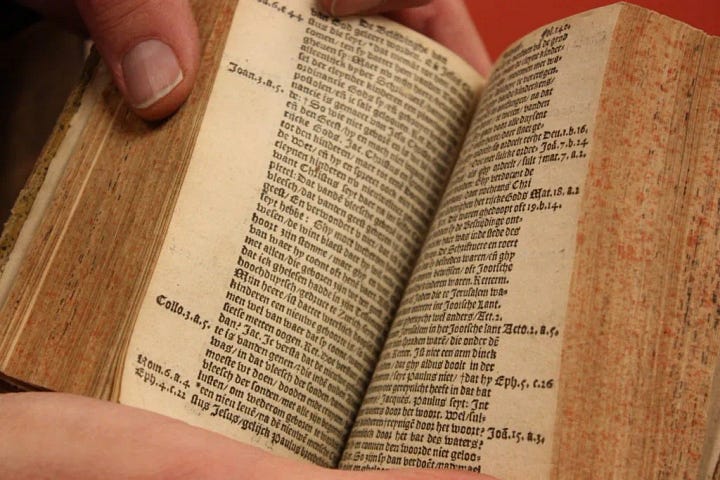

Not a breath after I sat down, virtually everyone pulled books out from little nooks below their seats all at the same time. A man rose to the 'pulpit' — which was really only a simple seat at the table at the church's center — for there was no altar — and began to almost inaudibly mutter in Old German. Then, a chorus rang out; a haunting chain of stanzas in the archaic language, sung melodically by everyone in the room but me. I fumbled for the book below my seat at the pew, leering over the shoulder of the stocky gent next to me to find the page number — 344. But this effort proved a complete farce; the words were all not only in Old German but were in a morbidly indiscernible font.

While I have never done LSD or any psychedelic, I immediately considered that I might be experiencing the nearest analogue to those drugs one might find in a sober mind-state — I had entered an otherworldly realm beyond my control, a province whose laws were not my own and consequently rendered the projects of my will into a shimmering absurdity. To my left, what seemed like hundreds of children in suit-jackets or bonnets were staring directly at me — the outsider. Old married women across the aisle registered that an interloper was present, eyeing me, and the men around me wordlessly glued me to my station as the ethereal chanting seemed to continue forever. Some part of me thought of exit — of the door. But like any psychedelic experience, I simply had to wade directly through it; whatever feeling in me said I was in the wrong place simply had to be 'processed' and accepted without action. Then the song was over and the men sat down.

One of the ministers began.

"Jesus wia to dän Groota Kjennich Herodes siene Tiet, en daut Darp von Betlehem, en de Jäajent von Judäa jebuaren. Un seet junt, een Stoot no Jesus siene Jeburt, dan wieren doa atelje Stiernforschasch ..."

Immediately, one of the very few elderly women on the other side of the ministers' table began to shut her eyes. In what seemed like an incredible feat, the old bird seemed to have achieved a deep sleep before so much as "dän Groota" had been said — all while keeping her neck perfectly erect. The filtered light of Brushton's agrarian plain gleamed into the building, setting the minister alight as he continued to speak in such hushed tones that I doubted anyone could hear him at all. My eyes were floating with impressions from the window's bright light, and though I felt an odd sense of calm as he carried on in an old and disused tongue, I nonetheless felt the magnetism of the exit door. And I, being the consummate nicotine addict, wondered how long it'd be until I could throw a Swedish snus up under my lip — I began to scheme a faux sneeze with a pouch of precious tobacco in my fingers, secretly and quietly bound for my nervous lip.

After a long droning sermon in Old German, the second minister rose and began to speak. This man, out of a sense of hospitality to the two English-speaking strangers he must've known the church was hosting this morning, preached almost entirely in English. He was markedly more articulate and was the first to speak with any remotely audible volume and projection — this man was a veritable orator. Yet his orational skill was profoundly humble; his manner of speech played no tricks. No, this was not the sun-tanned graduate of an Alabama seminary raising his arms in so many firy paroxysms and admonishments to donate to the ministry — this was a plain-dealing man who dealt gingerly with the Scripture. He had not a single trick up his sleeve, not today or ostensibly ever.

"Eye stand before yeh all not by any authority bet theh authority of theh scriptures," said the man, lowering his eyes in a portrait of spiritual simplicity for which there was no comparison in my memory.

He spoke for perhaps an hour, often stating that the sermon consisted "only of my own thoughts," and he seemed quick to remind us again and again that "as you leave, you'll have your own train of thought." He spoke of the importance of accepting misfortune humbly; of never doubting God's ways, even in cases of death or disaster, and he spoke these messages with an air of mystery that bordered on the mystical. His passion was palpable and yet unlike the vast majority of "preacher-men" in various denominations, he seemed to get no sort of a high or a buzz from his own passion for the Word. When he was finished, he simply sat down without fanfare, cradling his head in the large hands of a man who works and prays. Whatever awkwardness I had felt upon entering this place melted from me as I watched those hands; whatever reservations I'd had, the man had convinced me that I was dealing with the real article — these people were Christians in a profound, quiet, earnest sort of way that I could not help but admire fervently.

The rest of the service passed like a fugue; the word 'earnest' kept floating up into my mind. Without forcing it, virtually everyone I'd seen and interacted with in this place was radically earnest; to them, it seemed, the anxious middle-men of appearances and even technologies interrupted the divine rivers which flow through the metaphysical realities of being human. To anyone wounded by liars or exhausted by frauds, a stint in the Mennonite church might feel like a restorative sabbatical from a world that is so often wracked with the screaming anxieties of men that daily ripple and multiply and tire the world out. If the old woman couldn't help but rest her eyes, she did; if the young man in his black jacket and dull black shoes couldn't help but stare at the foreigner, he did. And if those moved by the Holy Spirit could not help but gaze contemplatively through the glistening gauze of the church's plain windows as they contemplated the infinite fruits of the good Lord — they did.

The majority of those present for the service seemed to be under the age of eighteen. In a county where most of the 'English' are either dying or moving away — this is a fact that may prove to be of profound import in the future of Brushton and towns like it. Brushton's Mennonite community began only in 2008, and only sixteen years later, they've multiplied so feverishly that this summer they'll be building a new church. Meanwhile, there are murmurs of Pennsylvania Mennonites being priced out of traditional Anabaptist strongholds — where land is simply unaffordable to any but the moneyed or well-connected. Young industrious sons of Pennsylvania Amish and Mennonites strike north for a chance at real success, finding the value proposition of North Country land to simply be too fantastic to pass up. When each family seems to be averaging four and five children per household, the demographical ramifications become obvious immediately — the future of northern Franklin and Saint Lawrence counties is going to be largely Anabapist unless current trends drastically change.

And who could complain? Turning fallow fields into rich dairies and derelict barns and homes into bustling homesteads strikes me as a massive boon to these counties. Moreover, the implacable neighborliness of these black-clad buggy pilots seems to have a rejuvenating quality on an otherwise collapsing rural culture. Perhaps there are clear lessons to be derived from the Mennonites as goes keeping a functional culture in working order; their earnest spirituality and loyalty to long-standing tradition, their willingness to strike out into obscure backwaters to find success on the land, their willingness to quietly continue with a lifestyle of inconvenience and 'otherness' for the sake of cultural continuity — all elements of a quiet and robust stripling culture on a forgotten northern plain. If this one-church enclave of Mennonites is indeed a sapling now thriving in the harsh world of the north, then by my predictions, this sapling will soon yield a forest. To my mind, nothing could excite me more. I welcome our plain-dealing neighbors with open arms — I look forward to seeing them again.

"We'll preach in the English for yer sake".....perfect.....wonderfully evocative as always. Thanks!

When you post about upstate real estate and opportunities there are two kinds of responses. Your urban upwardly mobile DINKs who fly into a rage at the thought of being out of walking distance to overpriced coffee. And the people who quietly nod, weary of the rat race and click "like." This post calls out to the latter.