Before launching off into this week’s article, I have a small request. I will explain. A writer neither hunts nor gathers nor farms — and yet he eats. As my subscriber count has more than tripled in only three months, I want to ensure that your support for my work is not misplaced: I want to constantly find ways to bring you my finest work as consistently as I can.

There is no manual or guide on how to operate a successful publication here: I am ‘shooting in the dark’. Your feedback can help me take my work here to the next level. If you would, please answer this survey so that I can continue to improve this publication and really earn my keep here.

As I might have mentioned before, I’ve recently begun to net about $800/mo from Substack — which just barely covers all of my most basic living expenses. There are times when I feel I do not deserve such a royal level of support; hopefully, with your responses, I can be certain I am providing you with all that you hope for in your subscription to Hickman’s Hinterlands. Thank you all so much — I continue to be overwhelmed with gratitude for the success you’ve generously given me thus far. Now, without further ado — American Water.

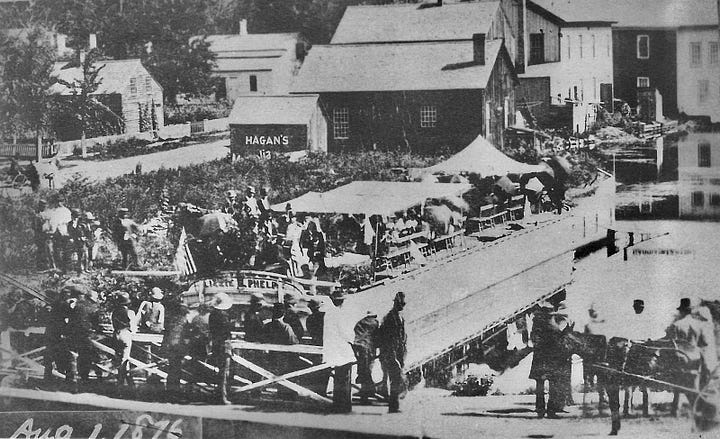

The circulatory system of the Empire State was once a maritime domain that cut through the hills. Shallow, straight, flat, never meandering except as made necessary by topographies of granite or cliffsides or gnarled wetlands and riverine chaos, our channels of murky water cut cleanly across pastures and timberlands and run straight through the centers of once-burgeoning villages and centers of commerce. Floating granaries, cedarwood scows, great barges and vessels gliding stoicly across the surface of hundreds of miles of canalwater all carried the spoils of an era of almost inconceivable commercial vigor. From one canal to the next, they arced downstream to old Gotham and to the wharves of Brooklyn — those cities whose adolescence still smiled wide across the bays and harbors with not a whiff of presumption or certainty for its future. Then, New York City's success was not a foregone conclusion nor a laurel on which it could rest in wrly placid luxury. Any possibility of ascending to world-wide status as a city was then something for which the whole state had to strive. This was the height of New York State's youthful days — the canal era.

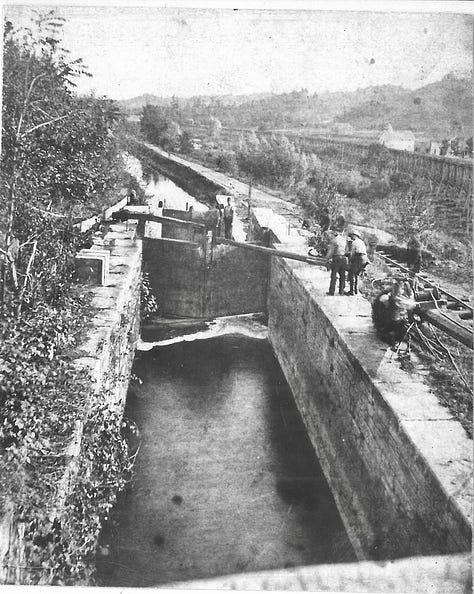

Running on diets of morning oats and noontime tipples, Irish stonemasons chiseled the archways and canal locks by hand, day in and day out. Boys barely old enough to grow a thin moustache felled ancient spruces and maples, wrenching their roots out of the earth with mule-driven machinery. Wizened old yeomen of Hessian extraction leaned over their porch-rails to give looks of shock or disapproval or awe at the endless ditch-digging that was taking place as the canals were being constructed. Meanwhile, mountain-faced titans of statecraft and economy in Albany mulled over the symphonic organization of stump-pulling workmen, immigrant labor pools, structural design considerations, the onset of ice, and interest-bearing loans — all in the name of feverishly building a statewide mesh of flooded ditches which were generally only four feet in depth.

Whole generations of mules knew nothing but the pin-straight dirt towpaths — with their course set dead-straight, they slaved over the hawsers of the vessels, pulling them miles each day. One wonders if these animals weren't unaware of the reality that because of the canal's frictionless surface, they were pulling hundreds of times more weight than they ever could dream to pull on dry land. Meanwhile the captains set the rudder straight, un-bothered by the usual gamut of nautical distresses and difficulties they might find on open ocean or even on a great river. No currents to set them off course, no tides, no furious waves — even fog and rain was of little import. So long as the mules remained in motion, the vocation of nearly every man on the canalboat was a romantically idle one such as men seldom find in any era or age.

And the towpaths veered dead-straight, with complete disregard for topography, property lines, city blocks, or seasonal flows. Back then, in a world of wending roads and buggy trails wandering madly about the hills and rambling across vast bogs and prickered wastes and mud-laced pastures, a definitively straight way of any kind was alien. For miles and miles, our canals flowed with eerie straightness, almost exuding an Asiatic elegance — their perfect straightness provided the ultimate contrast to an otherwise rambling world of curvature and topographical variety. This rippling aquatic heart of young America lay in Zenlike and crystalline repose — a shimmering meditation on constancy, peace, and contrast.

There, standing at the bow of a barge laden with the daily bread of ten-thousand men, a deckhand might stand before twenty miles of unchanging waters, flat as a bedsheet and droning infinitely forward -- thinking nothing, doing nothing, totally idle. One thinks, oddly enough, of Lao-Tzu:

Why is the sea king of a hundred streams? Because it lies below them. Therefore it is the king of a hundred streams. (Passage 66, Tao Te Ching)

The Atlantic lay below the Black River Canal; she lay below the Chemung and the Champlain and the Oswego — she lay below the Erie Canal and her wilder sister the Hudson. One could hate the Atlantic, spitting with rage against her quiet hydrological primacy — and find that their spittle lands in a creek which will flow to the Mohawk and down the Hudson until it mixes with the saltwater of the oceans. There, any astute observer of the world of waters and elevated grades will find a potent metaphor for humility: because the ocean has lowered herself before the world of bubbling streams and lively floodwaters, she is the winner.

The one who lowers themselves lowest will win silently and inevitably. New York's incredible canal system merely formalized this fundamental truth, making the waters legible and knowable, elegantly slashing across the countryside in perfect geometry. But these ditches were merely poetry written in so many shovelfuls of earth — a human rendition of a truth that all rivers have told for ages. And so it was that Gotham grew into the sprawling complex of power and relevance that it is today; it is a city that simply allied itself with the inevitability of an ocean. The canals were merely employed as temporarly handmaidens to that inevitable oceanic victory.

I ponder these things as I walk the pin-straight towpath of the Chenango Canal outside of Bouckville. Here, there is no dung of the mule nor is a single hawser-line in sight. The locks have succumbed to ruin and the villages that once prospered along the unassuming ditch are now somber voids where old general stores and taverns have begun to dodder in century-long retirement. Not a vessel has plied these waters since 1871 save for the canoes of young lads. Now the nature of the Chenango's fleet has changed considerably; little pieces of beaver-gnawed flotsam now constitute the flagship vessels of the waterway, and in place of bustling storefronts and docks there are springs where the moss weeps water down to the lilypads and cedars. Haggard brakes of stunted maple crouch over the water like dunk old lechers, and chipmunks ransack punky logs like pirates searching for a store of rancid acorns. Above the granary's rusting arches of steel and frayed cables, pigeons fly in galumphing formation, as if trying to establish themselves as Bouckville’s own Air Force.

A few milk trucks barrel through the town along the dusty US Highway 20, with no stops to make here. I sink into the leaning, half-rotting chairs outside the 100 square foot Chenango Canal museum (closed for winter) and watch them roll through.

Some of the antiquarian charm of the canal era is still present in Bouckville, of course. The architecture belies the hot and wild romanticism of the boom-town days; surviving every red line in every proprietor's ledger are facades of stone and long porchways where men once chewed tobacco in high summer. An odd building of stone stands tall by the canal section of town, looking nearly Bavarian in its shape and personality. Each summer, there is now a massive antique festival here where, no doubt, a lively trade of canal-era artifacts takes place. Piece by piece, the bones of the Chenango's bygone era are divided up in lots and brought to boutiques around the country, sold on Ebay, or traded for greenbacks at impromptu yardsales during the weeklong festival where thousands descend on the little town of Bouckville.

But today there are no thousands. In nearly seven miles of walking the towpath, I saw only one other person — an old man whose wrinkles were kin to those of long-gone boat-men. His face was stern and genteel all at once as he strolled alone along the ruined waterway, as if visiting the quiet grave of an old relative. At perhaps a hundred yards' distance, he was only a black dot in a tunnel of cedars, plodding almost motionlessly on the perfectly straight path of icy grass under the slatelike comforter of shapeless clouds. Down the trail, a rabbit hutch stood above the water, offering its inmates a commanding view of a ruined canal lock, and a half-rotted trestle of logs was employed as a dubious bridge. This, to me — is heaven.

One cannot help but marvel at the incredible effort it must've taken to construct this waterway. Opened in 1834, it ran ninety-six miles in length from Utica to Binghamton and took only three years to construct. Immigrants from Ireland and Scotland can be credited with building the Chenango, which was described as "the best-built canal in NY" by its promoters. Featuring 116 locks, 11 lock houses, 12 dams, 19 aqueducts, 52 culverts, 56 road bridges, 106 farm bridges, 53 feeder bridges, and 21 waste weirs, it was a truly colossal effort for what would ultimately be used for only forty-four years. Costing over seven-hundred million to build and maintain during its life (a sum that, accounting for inflation, would total over twenty-three billion dollars today) the canal only generated about nine cents on every dollar it spent — only to be supplanted entirely by the railroad's arrival in Binghamton in 1848.

To characterize the Chenango Canal as a devilishly disatrous financial loss would be correct in the driest terms — but it is not dollars and cents that build a nation. It is myth that builds nation; it is memory and beauty. These the canal provided in spades, and its gently-hummocked banks of bramble and clover became the metaphysical backbone of an entire generation of Upstate New Yorkers.

Perhaps today this backbone is still visible — its mythos still flourishes to the few who seek it. For the poetical drama of inevitability that one finds in contemplating the waters and their unstoppable ocean-ward flow is visible here in perfect form; one sees the interplay of man and land in this story with complete clarity. A river is wild; a wagon-trail is rough going. The riverboatman is humbled by the rapids and the carriage-driver is exhausted by the jostling of rutted roots and cobbles beneath his buggy's wheels. But the canaller is sleek and smart, he is at the apex of mankind's efforts to smooth the textured geographies of his country over into simple and clean lines across the land. A thousand locks and ten-thousand mules tow ten-thousand scows laden with fruits and lumber and pond ice and liquor; a man sits at the helm with a nip of whiskey and his boy meanwhile sweats on the mule train — the packet-boat captain is a kinglike creature who lives at the height of a landscape mastered by men and their ingenious works.

Yet canal-water is not different from the waters of the Mohawk and Susquehanna and the Chenango and Chemung rivers, all fed by so many tears of heavenly mountain water from the high and un-tamed hills — all of it is water, and it is all bound for New York Harbor and for the currents of an unstoppable ocean. Every bit of the somber tranquility of the beaches of the Atlantic is really no less present along this old canal — for wherever water is, there is inevitability. And indeed, it is the water that has run the lock artifices down, it is ice and flooding that has rendered solid columns of stonework into trembling stony hazards that faint into the brooks and swamped ditches.

All of it flows downward unstoppably; one finds that the projects of men are morbidly futile in the face of water’s endless wandering to downstream outlets. Every drop of it is drawn down as if by magnetism through stone embankments and across towpaths, bursting through the walls of hearty old aqueducts and across gulches where the Scotman's mournful thistle grows and the Irishman's old shovel-heads lay buried. Walking down the endless towpath, I simply stare, remembering all of this, allowing it all to coalesce at the surface of my mind — thinking of how easily men can be humbled.

But just as surely as water can leave even the greatest magnates and engineers and workmen frustrated and sheepish, water is nonetheless the essential element that cleanses the tired man of his fatigues and nourishes the crops of the radiant fields. Without it, life ends.

Not long after finishing the daylong schlep by the canal, I noticed a man with a jug by a wall of stone as I drove homeward. A green hose sparkled with water — a pipe had been driven into the stone, where perfect rivulets of glistening water formed along the moss and roots. Asking the man his business there as he filled his bottles, he simply said that he'd been drinking from this stream for his whole life — that no matter whether it was a drought or a flood, he'd always drank this water and so had his children. "I don't care what the experts say about drinking from roadside springs, this water's good," the man said. I leaned down to drink, nodding in agreement, mesmerized by the constancy of the spigot's flow. These waters would wend their way along the roadside to some culvert somewhere, no doubt, finding their way to the Chenango Canal and onward to the Erie and Hudson. They too, like the same floodwaters which had in previous eras destroyed embankments and canal locks and homesteads in former days — would find themselves kissing the saline droplets at the feet of Brooklyn's wharves.

"I've been drinking from this stream my whole life," he'd said. I couldn't help but meditate on his words as I continued the drive and sipped from my ice-cold jug. Perhaps we've all been drinking from this stream; perhaps it is our life. The futility of the builders be damned; let them build anyway and be quenched by the same old springs. The wending miasma of estuaries and bogs may claim any human effort without so much as a breath, but let us live it out anyway.

Perhaps, if a man is wise, he takes note of water's power and decides to do nothing — shambling like the sage, little and ancient, humbling himself before them as the ocean before great rivers. Perhaps he shambles along the old towpath, observing an ancient and implacable cycle, as idle as a canalboat sternman before the crackling springs which leak playfully out onto the stoneworks, eddied in the hilarious and Sisyphean dramas of his own species proclivity for effort.

As I've shambled in this fashion, I've always found myself giving thanks for our state's fantastic canals — their poetry is timeless; perhaps they are an American iteration of the Tao Te Ching. For while the eastern thinkers are of the Orient, and are in some sense far from the psychological architecture of the Westerner, the basic principles of Lao Tzu's meditations are nevertheless universal. The interplay of water and earth is primordial, reaching beyond the world of human noise and strenuous effort. Yes, the American man must build or he is nothing — yet as he builds in a world of ancient and undeniable forces, he walks with nature even if he struggles to conquer it. If he is observant of himself and his own history, he can only achieve a "Zen" that is not of Basho and Siddartha but is of Johnny Appleseed and Jefferson. He tastes the futility of his own efforts, laughs as if he has lost his mind completely, sits idle amid the primordial shadows on which his world rests — and begins again, knowingly and with joy.

In surveying our neglected and disused canals, who could not feel himself thrown into this cycle? Who could not taste the water from that old spring — that old spring we've been drinking from all our lives?

When my old man took on his second wife, a homely lady from Greene, NY, they eventually settled a little north of Greene, but south of the town of Oxford, on the east side of route 12.

The dirt road behind my old man's wound it's way to the bottom of the Chenango Valley, and to some ruins of this canal, which I discovered upon visiting my Dad for the first time, three years after my parents divorce and our father son relationship had been estranged.

The ruins stand like a memory never forgotten, but the water flows on, renewed constantly by the hydrological cycle that refreshes as certain as age.

The Lord may have interfered in finding me a wife who grew up less than 50 miles away from that spot on the old Canal, a coincidence like so much of creation appears to those lacking in spirit.

Thanks for this writing of yours, Andy, keep on keepin on.

There was a British lady, Harriet Martineau, who visited and travelled throughout the US for two years in the 1830's, and vividly described her journey on a NY canalboat.....wonderfully evocative essay, and love the photos and pictures.