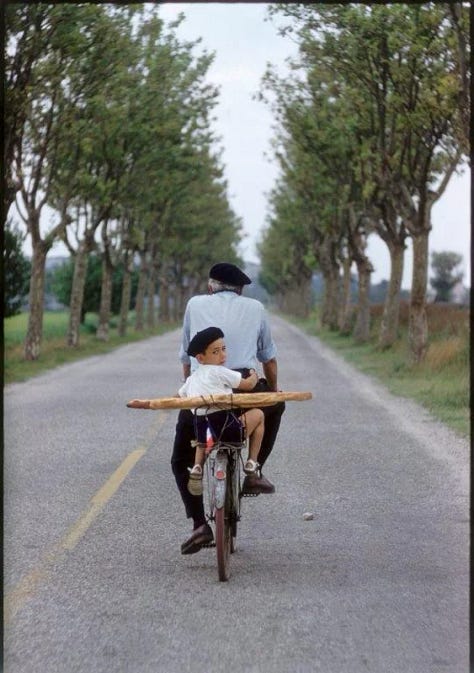

Imagine a man on a bicycle pedaling along a country road at dusk with a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread tucked into his knapsack. He is going between two rural villages surrounded by bucolic grandeur and pristine wild forest, and both villages are many miles from any city. His errand is not a lark or a bit of recreation; he provisions his household with whatever he can carry on his bike — because he does not own a car.

What country could such a man be residing in? Spain? France?

Surely, it could not be the United States. For the American, even an hour in a rural village sans auto is considered a catastrophe — the sort of thing only an extremely unfortunate individual would be made to endure, whether by way of automotive breakdown or grisly, tragic poverty. Even among our wildest eccentrics, the idea of being in a rural village without an automobile is simply considered a bridge too far — it is off the table. Only tourists who've blown a head gasket and Vicodin-addicted illiterates might ever suffer such a bleak fate.

Well, them, of course — and me.

For as of this week I am without an automobile indefinitely, and just this evening I've embraced the Platonic ideal of the Frenchman villager as my own — taking my bicycle on a jaunt to the next village over to procure a bit of fine wine which I am now sipping with all the abandon of a Provençal vineyard worker. My van had been on its last legs in the days leading up to Easter Sunday, and like an old farmer who senses the nearness to death of his favorite elderly sheepdog — I knew that my van's time was soon to come.

The Check Engine Light had been flashing for over five-thousand miles. As I drove down the county roads at nighttime my face flashed with orange, setting me alight as if I were a Jack-O-Lantern. Random cylinders were misfiring no matter how many times I changed the spark plugs and coil packs, and my gasoline engine sounded strangely like a diesel truck. New noises would start up, issuing from both the undercarriage and the machinery under the hood — and I knew that my old Honda's conditions were terminal. Even if they could be fixed, the rust on the frame was so ghastly, I'd have been a fool to spend the money to fix it, as its days were numbered.

When the tire popped on Easter, I was only twelve hours from the expiration of the vehicle's inspection — and it was obvious I could not pass another one without spending thousands of dollars on a lost cause of a vehicle. In what wound up being a fantastic twist of luck — I was only two miles from my hometown when the tire shredded. I kicked the hazard lights on and limped into the village, turning the heads of porch-sitting Easter revellers with the loud arhythmic sounds issuing from my wrecked rear tire. I coasted into my cousin's driveway, parked it, and said aloud that my "odyssey" with this old Honda Odyssey was finished.

As I walked over to my aunt's house to visit with the extended family clan, I proclaimed the news that it was time to lay my car to rest. Immediately, voices began to issue from all throughout the throng — "I think them things have three catalytic converters, I know a guy who's buying 'em for $350 apiece" and "That transmission is probably worth $400 — I'd part it out." It was as if I'd informed a gaggle of buzzards that a cow had died nearby; nearly everyone present immediately began scheming ways to turn a worthless car into more money than the scrapyard would pay me for it. When I further informed them that I'd lost both the title and the registration, the looks of disapproval flashed, until one beer-drinking cousin-in-law muttered — "well... I do know a guy."

In 1988, one of the chief ideologues of the Chinese Communist Party, Wang Huning, traveled to America for a period of six months. His notes from the visit were eventually assembled into a work titled America Against America, a book which a review in The Economist said succeeded in "seeing the weaknesses of the American system, but not exaggerating them." Two weeks ago, a blog called The Scholar's Stage detailed Huning's work alongside Alexis De Toqueville's Democracy in America, where I encountered the following summary of a portion of Huning's America Against America:

Wang describes America as a “regulatory society” and a “regulatory culture.” In America, “every area of social life is defined by certain regulations.” Wang points ... to the influence of high technology. Gadgetry demands compliance. Many devices—weed eaters, cars, anything that plugs into an electric outlet—are hazardous if used incorrectly. The citizen who withdraws money from ATMs, buys stocks, and cashes checks in an advanced economy has to master “a set of rules” that are “more complex” than the citizen of any underdeveloped economy ever deals with. Even photocopiers and office printers, Wang notes, “refuse to work if their users do not obey their rules.” So Americans learn to obey rules. [...] The machines that Americans “depend” on follow a pre-determined plan. They function smoothly only if the individual worker subordinates himself to these plans. When all works as it should “the only commands [Americans must] obey are that of a machine [...] By doing this the individual becomes something like a machine himself.”

The vista Huning provides here offers a clear window into the mind of 'the automotive man'. To the American motorist, the motorcar occupies a position of extreme mythical importance; it is as central to his identity as the horse is to the Khan's warriors on the Mongolian steppe. Without his car, the American is nothing; without the machinic qualities which the automobile has imbued him with, he is aimless. The moment the engine unexpectedly cuts out and the American motorist finds himself standing bewildered along tracts of brush abuzz with insects and birds, he finds his position to be harrowingly hopeless. Such a man can be saved only by his own mechanical wit — an increasingly dubious prospect in the era of computerized automobiles — and, barring this, he is adrift.

For in the image of his car, 'automotive man' is himself a machine in likewise fashion; the car is a machine for transporting man, and man is a machine for both maintaining his machines and for making the money required to keep them up. Moreover, man's imperative is to navigate the bureaucratic machinery that surrounds the automobile — paying his tickets and tolls, registering, insuring, and inspecting his vehicle. Over dinner, the 'automotive man' may have lengthy discourses about driving laws, brake lines, durable car models, and highway construction projects. In many respects, a man and his automobile are a single entity.

Machine-man is both subject and author of bureaucracy; the cycle he engages in is self-reifying. By consenting to the machinic conception of humanity, he both submits to the supremacy of the machine and spurs the essentially bureaucratic nature of the machine onward into every domain of life. His world becomes a world of maintenance schedules, monthly bills, mechanical inspections, vehicle purchases, and trips to the gas pump. These actions take on a cultic and near-religious gravity that is central to his identity — and yet, they cannot constitute the sum total of his person, and he at least half-consciously knows it. And so it is that when the limits of machine-bureaucracy are discovered and observed, the machine-man may take a trip to Provence and revel in the bicycle-pedalling characters of the walkable streets — or he may say "I know a guy" when an un-titled vehicle must be sold to a scrapyard, in defiance of the bureaucracy that surrounds the automotive machine.

For ultimately, the machinic conception of the human spirit is devoid of metaphysical content. The automobile is at bottom a hunk of metal; it cannot supplant more ancient conceptions of divinity and identity even where it appears to be capable of doing so. The center of its mythos lay in human rationality and will; the machine is a creation that is of man and not of God or any supernatural force whatsoever. And so it is that the adoption of the automobile as a core component of the American mythological identity has been an ersatz development in our religious history; it is a sort of cargo cult whose limitations are finite and therefore not divine in their essence. And yet, this contradiction being clear to any who examine in earnestly — the automobile is nevertheless raised to the status of a deity in the minds of men.

What could rectify the machine's inadequacies as a half-conscious expression of faith? What is the diametric opposite of the human will and its projects? What is the antipode of bureaucracy?

The chief domain in which a human soul disabuses itself of rational, bureaucratized modes of thought may very well be that of romance; not merely of romantic love, nor solely of love in general — although these are of incredible importance in any complete spirituality of man — but of life's romance. The style in which men live, beyond what is rational, sensible, or measurable — the somersault of glistening olive oil dribbling from the carafe onto the sunlit bread; the kiss upon the seawall lashed by the roiling vernal waters — the reckless abandon with which a child engages in his play, his dance, his creative ambition. The inmate of machinic bureaucracy craves a luddic release-valve; he yearns for a moment of release from the shackles of process and schedule. He finds it in the anarchic practices of the junkyard, in the vacation to the spiderweb of hilly streets of ancient cities, and indeed, he finds it in the selfless love of his brother, where schedule is interrupted, process is ignored, and the rational concerns of the day are eclipsed.

These reflections are congruent with the season of Easter. For as it is written, God is love itself; He does not merely exemplify love — it is Him. And God so loved the world that he sent His only begotten Son to suffer and die for the sins of the world; Christ Himself was love incarnate. Even in the final moments of His life, in His incredible agony, He begged His father's forgiveness on his torturers — Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do. Everything about the story of Christ is, to the machinic man — outrageously irrational. His willingness to suffer and die, His prayer of forgiveness to His murderers, His extensive preaching against worry — Jesus Christ was the ultimate in love, and the vision of humanity that He taught and lived is the final and most complete antidote to the distorted life of the 'machine-man'. The Son of Man proved that the machinations of the rational mind provide an insufficient yardstick against which to judge human action, hope, and ambition.

That in the three years of the Lord's preaching, He would teach so extensively against worry is of supreme significance, for insofar as I have ever been able to tell — worry is the essence of bureaucracy, and additionally, bureaucracy is the essential and self-reifying logic of the machine. For every bureaucracy that has existed has been justified by the question of so many "what if's," and often, the most successful mechanics are high-functioning neurotics. The bureaucrat's sleep is nibbled away and disrupted by fever regarding late paperwork and fine print; the mechanic's sanity is eroded by the thumping in the piston that eludes his diagnostic ability. In both cases, there is a vision of a perfect world where all things are knowable about either system — but the all knowing One is not a mere man, and never could be. Even the collective "we" of humanity's technicians cannot supercede the knowledge of the Creator; and so it is that we worry in vain, precluding ourselves from the reckless abandon of love with all the nervous anxiety that is etched into the machinic conception of life.

In short, the risk that inheres in the adoption of machines as central elements of human culture and identity is the possibility that their users and technicians will be fooled into imagining that mankind is in control. Once this supposition is accepted over and against the apparent foolishness of un-worried brotherly love and innocent trust of God — the logical conclusion is death. For while mankind can never succeed in his hope to possess all knowledge which is germane to his own technological efforts, his attempts to do so inevitably lead souls to despair, away from love, and away from the romance of human life, which is a mysterious and inconceivable God-given gift. Truly, Christ's vanquishment of death was and remains the ultimate disputation of the idea that man is or could ever be in control of the world and its souls; His rise from the tomb is the permanent triumph of love's implacable meekness, simplicity, and apparent irrationality.

Without this, cultures descend into an inhuman state, dignity erodes, and freedom is only a macabre half-freedom.

Of course, whatever the merit of these reflections — which are only the imprecise ramblings of a car-less villager now halfway into the bottle of wine he brought home on his bicycle — they do not change the reality that the great majority of Americans are essentially comfortable with our collectively machinic state. At least — we are comfortable with in insofar as the rational surface of the intellect is concerned. The bleak reality is that the state of mental health in the United States is deplorable, and that spiritual concerns are now obscure in the mainstream. Deaths of despair, appalling suicide rates (especially among young people), rampant drug overdose deaths, and sky-high rates of anxiety and depression diagnosis all strike me as corollaries of a larger spiritual incongruity between the human soul and the socio-technic order we have constructed.

The ailing of a human soul cannot be adequately addressed by bureaucratic means; AI therapists, robotized crisis hotlines, psychiatric pharmaceuticals, and neurological interventions are merely treatments of symptoms rather than underlying causes of grief and anguish. American society is now only a society in name only; it is in actual fact a sort of anthropomorphized factory or waiting-room. The very technics that seem to have upended human community, religion, and ontological synchrony are viewed to be the solution — a further testament to the self-reifying nature of the machinic mode of human life.

In actual fact, if thousands of years of religious canon are not to be haughtily dismissed as mere superstition, the actual solution to the current of widespread psychic grief that is now so prevalent is likely to be found in actions which completely defy our native rationality and machinic social norms. To "trust fall" on the world, to live romantically, to embrace a conception of life that is a little meek, a little simple, a little foolish, and above all, a conception of life that takes it as a given that the human intellect is not capable of conceiving of the whole picture would probably address our ailments. To let one's machines rattle apart along the highway, to laugh at the shredded tires and blown cylinders, to fail to report for muster as another machine-man, to fall off the maintenance schedule and to forget the paperwork — these are the human things which leave room for God to lead. To sell all we have and give it to the poor, to walk along the roads as pilgrims, to pedal to the next village over for a bottle of wine, to give thanks for our bread among friends in the sunlight of the springtime — who could say no?

Truly, He is risen, and at Easter Mass I prayed to be led. Hours later, my van's inspection expired, my tire blew, and my cousins began to pick my vehicle apart. Now, I have a bicycle, and I have been relieved of my $117/mo insurance bill, ~$250/mo gasoline bill, as well as the threat of an expensive breakdown and subsequent mechanic bills. Now, my expenses are below $1000 each month. Soon, I'll be trimming them down even further, and departing indefinitely yet again. And tomorrow, I'll be raising my thumb along the road, doing what I was born to do — foolishly trust-falling on the public, sleeping where I please, and with any luck, finding my way into some of the best of what America still has to offer.

Happy Easter to all of you — let us have a fantastic spring together.

This is probably your best essay yet, both thematically and mechanically. Throughout your work, there are strong themes of increasing your own autonomy and agency. You acknowledge, however, that "tomorrow, I'll be raising my thumb along the road, doing what I was born to do — foolishly trust-falling on the public,". This is a bit tongue-in-cheek and made me smile, but I also wonder if you ever have difficulty reconciling your desire for agency/autonomy with this semi-reliance on the public. Public lands, hitchhiking, libraries, etc. To the casual observer, it might seem contradictory but I anticipate you have a different and deeper understanding and may not see it as contrary at all. Can you speak to that?

Beautiful. I've been thinking about this post from Mark Kutolowski about Time and Eternity ever since I read it: https://metanoiavt.substack.com/p/time-liturgy-and-eternity

The way he describes how certain machinic activities take us away from eternal time while others seem to better allow for our perception of the non-linear, eternal truth that we are "hid in Christ" has stuck with me. You said it differently and with more humor. I can't wait to read this to my husband and son who are both mechanically talented and are rebuilding and old truck together. Turns out the man who is giving the truck to my son can't find the title AND the dirt road that leads to our new house is impassable due to mud. We are thinking about oxen as an improvement over engines of many kinds.

Clara