I. Hitchhiker’s Guide to Heartbreak

This essay was originally published one year ago in Issue #3 of the print-only County Highway newspaper. I’ve reprinted it here for this week’s Desert Double Feature. Thanks for reading — enjoy!

There are days when whole cities are harried and unshaven; sleepless nights when the sunrise brings no cleansing promise to man. Apocalyptic neon columns cut the dawn, leering over the desert, where hundreds of thousands of souls linger in disillusionment and fear as the sirens endlessly scream. It was the morning of October 2nd in Las Vegas, 2017. Sleep-deprived nurses from area hospitals dragged themselves through drive-thrus for coffee, listlessly muttering their orders, shocked by the carnage they’d witnessed only the night before.

In line at the Goodwill in Henderson, just south of the city, one of the nurses seemed liable to combust. His eyes hung down, morose and lamblike, somehow ancient in their grief. He moved up in line clutching a t-shirt bearing the word “HOGWARTS” – a gift for his girlfriend, he said. It was only his first week as a clinical nursing student. As the cashier’s gaze met his glassy, reddened eyes – he nearly doubled over in wild, hot sobs, murmuring as if speaking in tongues. But before the scene could get downright Pentecostal, he rose up in a bleak soliloquy and held all present spellbound, offering a testament to the crowd of all he’d seen at the hospital the night prior – the blood, the stitches, the dangling eyeballs, the suicidal parents of mangled teenagers. A hulking New Brunswick lobsterman on vacation held him close, sobbing softly. The wispy old bird at the register offered up a prayer.

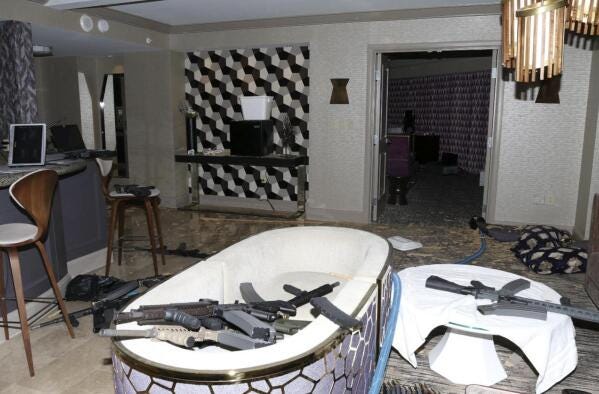

I had a long and weird journey ahead of me. Outside, my recumbent tricycle was locked up, its black, lay-down-style seat being warmed by the indifferent, boyishly potent Nevada sun. It represented an experimental effort; an attempt at traveling by means other than my usual mode, hitchhiking. I’d slept on a Las Vegas bartender’s couch the night before, where I was gruffly informed that I had overstayed my welcome and that I should depart in the morning. As the shots ripped down from Mandalay Bay — over one-thousand rounds in all — I bolted a weedwhacker engine to my tricycle and installed a hackneyed belt-drive system for the rear wheel. Sixty souls perished as I packed, and another 867 were wounded. Now I was headed for Mexico, after purchasing some steel water bottles to fill with gasoline.

Leaving the Goodwill, I was haunted not only by the shots I’d heard and the people they’d killed, but by the wearied, broken eyes of the nursing student whose tears I’d just witnessed. His heartbreak was contagious and had entered into me as well.

By that point, I had traveled the United States for four years, seeking some semblance of a living ember of a vaguely ‘“original America”’ — the romantic, mythological America of corn-husks and altar boys and twinkle-eyed riverboat pilots. What I found instead was a disheveled, schizophrenic country — an America of fentanyl and strip-malls and the endless ‘“suicide gaze”’ of commuters that only a hitchhiker knows. The massacre at the casino felt like a capstone on my disheartening half-decade quest for American romance — the coup de ’grâce of late capitalist psychosis. Hitchhiking even so much as one more mile seemed spiritually impossible to entertain.

Thirty-five-miles per hour was all the speed that my thirty-eight cubic centimeters of engine could give me. As I departed the sprawling Leviathan of Greater Las Vegas, cars careened madly down Highway 95, and police cars moved in wildly varying rhythms of acceleration that plainly showed the fatigued condition of the officers. I was travelling southbound.

Now — desert. Ninety-nine degrees, a gallon of water, a gallon of gasoline, and a sleeping bag. As if the delirium of the events of the last twenty-four hours wasn’t enough, the sun was punishing me, melting my brain into a demented hallucinatory state. How imperiously that highway strikes south, a perfect contrast of black pavement against the empty, arid ochre of southern Nevada. The straight line to Bullhead City is flying with demons, and I’d met some the last time I’d been here. Nursing a sunburned thumb north on the road to the Hoover Dam — that obese and frightful concrete testament to American progress — I’d met meth-heads and has-beens and scolding Mormons and homosexual Mexicans and brightly-dressed German tourists. Searchlight, Nevada emerges along the mountainous ridge as a gaunt hideaway for the unknown, what with its dimly-lit casino and nicotine-yellow air.

On the highway, I had become a receptacle for confessions and conspiracy theories from thousands of drivers. The suicidal banker. The loon-eyed pistol-packing rancher who swore that “the Africans” would “get real high and do a big 9/11 attack in Kansas City.” The Mississipian 13-year-old who smoked cigarettes and swore he’d add Oprah Winfrey to his “stable of hoes.” The perverted hippie acupuncturist on his way to divorce court.

Just as I nearly fell unconscious, my insane tricycle contraption rocked and slid into the sand of Cal-Nev-Ari, Nevada — a shimmering hamlet of less than two-hundred sunburned souls. Wordlessly, I sauntered into the town’s only public establishment, a casino-bar — where I spent my last hundred bucks on a motel room and ten cans of Miller High Life. I was nearly on the edge of a heat-stroke.

Sloughing off the fever in my little room, the sagebrush and blowing alkaline dust of the desert faded from memory. Visions of home taunted me with memories of the Erie Canal and of tangled forests and maple syrup snow-cones. Upstate New York, where I grew up, is possessed of an archaic and stiff sort of order and Yankee-ish quiet. No casinos, no sun-poisoning, no bullet casings or grieving cities of neon. My hamlet was a sturdy and frugal paradise of obscurity and peace, where snow came in off the lake and the maples lilted in colonial winds. Murmurings surfaced in my vagabond mind. I had been on the big hard American road for far too long.

I woke to the groan of the air conditioner in my little room. The sound it emitted was in perfect tune with my twin hangovers — from not only beer, but a foolhardy amount of sunlight. Perhaps grief was at work on them both. I struggled to remove myself from the bed. Another blistering day on my tricycle felt unthinkable, but I departed.

As I rode, the land rose stiffly at an eastern turn. My rear axle spun red hot and my kill-switch broke, but I rode on with a fatalistic smile, embracing my own lunacy. The Laughlin Highway was flanked by psychedelic formations of pinnacles and bleak rocks, the haze lingering over the valley below suggesting some dim, primitive recollection of the Khyber Pass. Facing east toward the Colorado River, a descent of some 2,700 feet was ahead of me, covering a mere ten miles. I jammed the throttle down so hard it got stuck, and with my tricycle careening wildly beside flying eighteen-wheelers, I surveyed the river valley below. I thought of death: my own, perhaps, here along this rocky highway or at a stoplight below, and of the sixty-three others who had departed Las Vegas in a far ghastlier and more tragic fashion than I had the night before last.

I coasted into the Safeway parking lot in Bullhead City to rest my rattled nerves. Inside, I shoplifted a melon, tucking it underneath my ribcage in my overalls like a rippling, corn-fed American beer gut. In what felt like a stylistic nod to Aladdin, I began slicing into my pilfered honeydew beneath a sun that might as well have been Arabian, half imagining Las Vegas as Jafar’s secret, evil lair in the desert. And there, not a furlong from me, was some kind of spiritualist bum in a heap against the wall, clenching some beads. His name was Vaughn.

“Man, I’m too ugly to hitchhike,” he declared as we traded life stories. He was wet-lipping a hand-rolled cigarette, salivating as he sucked a pitifully tiny stream of smoke from the soaking paper. His eyes gleamed like a monastic as he told me of “some bad investments before the 2008 crash,” and a “forceful penchant for intravenous methamphetamine” he’d only recently overcome.

His command of the English language was uncanny — I couldn’t think of the last time I’d met a meth-head who might use the word “intravenous.” An encounter with a jailhouse Priest had led him along the path to sobriety and salvation, he told me, and now he was on a quest to “unmoor himself from the immeasurable darkness of his own moral disfigurement,” an effort that included a reconciliation with his old wife. She was holed up in Needles, California, some twenty-two miles to the south — or so he’d heard ten years ago. The juice of the melon mixed with the saliva on his cigarette as he looked away, spitting.

I found a friend in Vaughn. We discussed the plausible demonic oppression of Stephen Paddock, the mystical virtues of the Rosary, and the more uncomfortable truths hidden in the Book of Matthew. He laid out the drama at the local soup kitchen, the various police officers he’d gotten reprimanded by the City Council, and his efforts at renovating a storage unit he had rented into a clandestine “winter palace.” His academical and pious earnestness was a tempest to my furious and apocalyptic mind-state on the road out of Vegas; some harshness or disillusionment melted from me as I relaxed alongside this kindred spirit. In a moment of mystical exuberance, I offered him my trike.

“It’ll get you to Needles to see your woman,” I told him. When he said he wouldn’t accept the gift, I shook his hand and walked away, leaving the contraption there. He offered to beg a bus ticket for me at the soup kitchen, an offer I refused — I was going to hitchhike home.

When I had first undertaken the great journey that would lead me to hitchhike over 150,000 miles, I had really set out to find Huckleberry Finn’s America, the America of Johnny Appleseed and Norman Rockwell. I was a hayseed’s hayseed, a loner from a sleepy antiquarian outpost on an abandoned canal-way in Upstate New York, over five hours from New York City. It’s a place where the happenings of Second Avenue are as foreign as those of Shanghai; where embittered yeomen drink nightly at the American Legion and genteel old buzzards pass the spiced rum at Revolutionary War re-enactments. Those roughshod hills in the forlorn reaches of the northern Mohawk Valley imparted on me a strong sense that the lineage of the American mythos was still flourishing.

To set off as a hitchhiker, then, was only fitting — and to return as a hitchhiker was the only sensible epilogue to those years. With a brief embrace, I was again traipsing southward beneath the familiar burden of my rucksack, thumb to the sky.

II. A Desert Rat Comes Home

That I am a man of a thoroughly Eastern persuasion should be apparent to anyone familiar with my work. I am a lover of the gnarled and rambling roots and the sodden marshes that squelch beneath one’s rubber boots — an afficionado of leaden overcast skies and somber glades of sugar maple and hickory. To a man of my disposition, America’s Western deserts might appear only to be a vaguely terrorizing landscape of dessication, exposure, and poverty — and these days, that’s exactly how it looks to me.

And yet in earlier times, I have been drawn to that dry, treeless world, where the violence of the sun exposes every blemish on the soul and every weakness of the body. Like a fast draws the flesh of a penitent taut and sends his mind fluttering into mysticism and prayer, our deserts drain the dross from the human heart, laying bare the skeleton of the soul in a harrowing still-life. That the arid Western interior has a “psychedelic” character has often been remarked on, and I find this idea to be utterly, frighteningly true. To walk out into the desert is to die a little; it is to launch oneself off the precipice of sanity and calm, out into a cosmic trip of dehydration and delirium.

Many such ‘trips’ made me the man I am today, and I cannot deny that my desert days still linger in my mind with equal parts fondness and trepidation. Yet, no more. Something has changed. The piss and vinegar of early manhood has fled from me; the desert only scares me now.

In the winter of 2016, a clean-shaven man from Delaware picked me up along the side of California Route 111 — a lonesome vein of asphalt snaking through California’s low desert. His name was Carl, or Mike, or Tim, or David, or something like that; he looked like a man who could be on the cover of Men’s Health magazine, and he was on a business trip. Having landed the day before at the San Diego airport, “Carl” was taking the scenic route to a conference in Palm Springs. By then, I was a certified ‘desert rat’ — I was on my second winter in Imperial County, living out in the alkaline hardpan with a gang of hippies and dropouts who congregated there each winter for the mild weather, indefinite free camping, and the unlocked potable water spigot behind the Chamber of Commerce building in Niland.

“I feel this place in the pit of my stomach,” he said, looking forlorn and pensive. “It’s my first time out here and frankly, I find it frightening. Even flying over this place in a plane, my gut said — there’s danger here; you’re dangerously alone. Go home to the trees, where it’s safe.”

I had no idea what he meant. Back then, the desert was to me a sort of oasis of realness — a place too harsh for liars, fakers, and the bogus platitudes of the botoxed chumps back east on the I-95 corridor. It was a place where misfits, war veterans, meth-addled bums, eccentric refuseniks, and rustic Mexican campesinos all congregated in dusty concrete-block Cantinas; a place where the oven-like sun melted plastic and turned every trace of civilization’s technicolor facades to a ghastly, nicotine-like shade of burnt yellow. It was a harsh, naked world that even the Indians referred to as “the valley of the dead,” and the far-off horizons let a man see what was coming. Absolutely nothing sneaks up on a man who decamps on a high desert hill — nothing, that is, except himself.

Two winters before, on my first visit to the low desert, I stood at the truck-stop in Mecca, California, a mile east from Highway 111 on my first jaunt south of I-10. That truck stop might still be my favorite in America — a Mexican-style ‘mini-mall’ with long, dim stone corridors; Cumbia was playing on the speakers, and Guatemalan girls were selling jugo de coco and figurines of the Virgin Mary from little hand-carts. As I walked east, a rusty Econoline van swerved into the sand within minutes, tossing their back door open and beckoning me in. It was 101 degrees; the wind was kicking up torrents of sand and dust through the date palms — the scene felt downright Arabian.

“Get in, man!” was all they said, and I did.

I lay among the tools and beer bottles in the back of that van, gazing out the window at the endless khaki-colored flatlands of the Sonoran Desert. A weak stream of A/C limped toward the back seats; tools rattled over the bumps in the road, and I was covered in sweat. We careened in silence through depressions in the road that flooded only once a year, and my driver informed me that on the rare occasion that it does rain in this valley — everything turns to mud, and everyone is immobilized by flooded roads for at least a few days.

Then the driver and his wife lit a joint and looked back at me through a cloud of smoke. The woman said: “Oh, man, I know where to take him..” And her husband nodded, grinning.

I didn’t care where they took me; I hadn’t even asked where they were going. When it’s 101 degrees outside, you aren’t thinking about much; the mind slinks into a state of total vagrancy — you do not ‘do’ or ‘go’ or ‘think’ so much as you float through the day’s burning hours in a languorous, mindless fugue state.

We took a sharp turn and flew down a rough road that cut through the low-slung octillos and sagebrush, and in the distance, a Mexican train shimmered southward — seeming to levitate off the desert’s moonlike surface in the daytime heat. One turn, then another, we pushed deeper into the dryland boondocks, until the vehicle slowed and I said my “thanks” and stumbled out of the van to get my bearings.

To my right, US Air Force planes were flying over the Chocolate Mountains Bombing Range, dropping cluster munitions that spread like explosive glass across the lifeless brown mountainsides. To my left, an expansive controlled burn was taking place on federally managed “grasslands” — where no grass could survive, and the flaming sagebrush was kicking up ash in giant dark clouds. And in front of me: A naked, silver-haired 75-year-old woman lazed with open legs by a fetid hot spring. She was alone, wearing a gas mask attached to a bong, taking giant rips of cannabis smoke into her lungs and sizzling back, violently coughing smoke into the warm brown water.

“Where the fuck am I?” I mused aloud as the van sped off.

“You’re where you’re supposed to be, brother,” a man answered. He gave me a Bible and told me the end was near.

Perhaps it was.

These are the “little deaths” one dies in the American desert. Liquor and blood and gasoline mix in the dust storms and ovenlike zephyrs; one’s flesh purges the old worms that thrived in them back east. Meth zombies writhe in the irrigation sluices — Mexican peasants cackle at the Carniceria, slugging on midday Micheladas, and gold-toothed mafiosos stare down their enemies in squalid village streets. Life back east becomes only a weird memory; it hangs heavy on the recesses of the mind like old, wet mercury. And vague portraits of life “back there” in the land of rain and grain and black tilth sneak into the brain on glistening hot days — only to slip away as easily as they came.

The man was right — the end was near. But it was not the end of the world nor the resurrection of the Lord; it was the end of my world — the world of my early twenties.

For in the days that followed my arrival at that bizarre hot spring, I would find at least one thing in common with the man from Delaware — I would feel this place in the pit of my stomach, too. But what might come to a middle-aged man like “Carl” as an ominous and gut-wrenching warning is, to the twenty-one-year-old, an exhilarating launch into a high-octane fever dream. For the adrenaline rises in the stomach as a young buck reaches for the titty or leans on the accelerator or shoots tequila doubles; butterflies scream through his body as he ducks off into the bush to shake the cops from his tail, or as he rolls bloody-knuckled in the gravel in a wild scuffle. Where man at middle-age might feel these same sensations and feel only a dreadful sense of urgent danger — the young man runs to it, on a pointless hero’s quest for something real.

The desert was this for me — a departure from the stiff, humid effrontery and the tepidness of the East; a furious sprint into naked truth. And in this way, the desert comforted me, for the desert cannot lie. In its elemental despotism and abject social dysfunction, these bleak and arid quarters enact complete control upon the flesh in an arena of danger; physical limitations and harrowing brushes with his fellow man govern the ‘desert rat’ at his every turn. One cannot will themselves beyond thirst and exhaustion; they cannot conceal the haunting tremors of heatstroke or hangover. The desert man lives one inch from the august limits of body and earth, always at the edge of life itself — in a landscape so vast and empty that no man can hide a thing.

In this respect, it is the most tantalizing of locales in which to sort through the angst and anxiety of the teenage years. The lies, the fallacies, the omissions, the smirking half-truths of the adults about matters as grave as divorce and paternal lineage; the insufficient answers to questions as serious as “where is my father and mother?” — all of them boil to the surface of a young man in his red-eyed traipse through the American desert, pushing him to burn away his innocence as an offering to the insatiable idol of teenage anguish.

But one can only burn so much before the glorious and limpid clarity of desert dawns rises in the young man’s bones. Like the end of a century-long war of attrition, a cautious feeling of victory rises slowly in the heart; the long fast of aridity and desolation has untied a thousand knots. A man begins to walk with certainty and calm; his smile is no longer forced — liquor and lust begin to bore him, and the sunrise becomes the most fascinating part of his day. Solitude comes not as a demon but as a friend; and in some strange way, his sacrificial ejection of his own innocence into the flames has made him even-keeled and capable. The desert has given him a profound gift; a gift that came with it scars and harsh memories, but a gift nonetheless. Like a war, he has emerged, and the old struggles have been blotted out and bleached into oblivion by the harsh Western sun.

As the calmness of this victory rose in me, the desert meant less and less to my heart. Calmer and calmer, stronger and more resolute, a manly contentment penetrated my bones — and an unexpected fondness for the tired old East visited me. First, it came quietly — fond memories of slushy old roads and turkeys in the cornfield, visions of cabins out in the hemlocks and flooded springtime streams. Later, it swelled; I began to obsess about the East with great passion — even to crave it.

For the West is a world of sun-tanned youth and dumb brawn; if such land were a man it would be a strong, sultry, muscular creature of a man — a man who runs wild, bucking and kicking; a man who’s got a chip on his shoulder and something to prove. By contrast, the eastern realm is a tight-fisted, frugal sort of place; the land of the wiry, old penny-pinching buzzard and the sober swamp Yankee — a country that snarls: “I am what I am” beneath the funereal overcast.

Not too many weeks after my ‘escape from Las Vegas’ on my motorized tricycle, I found myself back in that country, staring out at the beavers in the muck and mire. Snow was marching in off Lake Ontario; I nursed a Labatt Blue and weighed all that’d been changed in me by my years out West. With no craving for danger and no further need to turn and burn at all hours of the night, I began sleeping longer and reading more. I’d sink into periods of profound, contented silence; I’d walk for hours alone along the old Mohawk River and smile. And I remembered the man from Delaware and his reaction to the California deserts. I understood it now.

Now, every time I go West, I feel the howling loneliness in my stomach, just as he’d described. There’s a danger there; a grim, solitary poverty I can’t abide anymore. I think of the gunbarrel raised from the Mandalay Bay windows and the sickening metal clang of the shots fired; of the bleak road south to Bullhead and Needles and of sad old Vaughn clutching the Rosary at his storage unit. I think of the desolation along the Coachella Canal and of long, liquored-up nights at Bombay Beach; or of getting arrested in West Texas with the Juggalos. Sad old country songs and the slowed, gangster Cumbias of the Cholos; human bones by the octillos on the border and sandstorms that had me curled up in the fetal position for hours on the desert floor.

I shudder at these visions now — they make me want to slink down under a spruce bough and hear the grouses rustle in the corn; they make me pine for the old Erie Canal and for pancakes and Canadian bacon as the snow flies by the windowpanes. Out in the desert, the end is near; the apocalypse lives and flies like a demon — but out East, it’s morning all the time, and a man’s contended smile on a rainy day is his greatest wealth.

Now, the desert is only a memory to me. God bless it — my next trip there is liable to be my last.

Lovely post—I enjoyed very much reading it from my Thanksgiving-week perch at the Amargosa Opera House in Death Valley Junction.

Beautiful, bursting with imagery, some of the weird desert stuff a bit like Steven King, maybe in his "The Stand"......hope Vaughn has made it........