I was raised by a man who thought the American Revolution was a ghastly mistake. It was obvious to my grandfather that the stern traditionalism and stability of the ancien régime of old Europe was an incomparably preferable arrangement to the cowboyish derangement of the American experiment; that it was human nature to need a form of government capable of outlasting the feverish whims of the masses and the pitiably peevish fashions of men. In a purely theoretical discussion about politics, my grandfather would at best concede that the founding of the American nation was a noble experiment — and this was about all he could grant it, though his instinct for realpolitik did not prevent him from voting nonetheless. To him, Canada did not symbolize what it does for many American liberals; he did not threaten to "move to Canada" if someone got elected or a political change was made in the States — the Dominion was not, to him, a utopian antidote to America and her problems. Far from esteeming her as the perfected North American model, my grandfather instead eyed Canada wistfully from below, always cautiously intoning that they might've had the right idea all along.

For the American vision is one of cowboys and tycoonish delirium; her history is one of hasty plunges and decisions of an essentially belligerent and boyish character. Like a 3,100,000 square mile sandbox for the playground's wildest young bucks, America is a haughty, hasty, feverish realm of extreme possibility and risk. If platitudes are mouthed, they are only in service of liberty — humanity and the mechanism by which culture operates are almost always an afterthought. Even human nature is viewed as a modifiable thing in America; whatever one must do to extend their capabilities, to increase their influence, to settle and to build and to light conflagrations of profit or unrest — the Yankee man must do it, exuding dynastic extremism or else finding himself ruined by those who've bested him. My country is an exhausting place.

The Canadian meanwhile strikes me as a paragon of prudence and fraternal warmth; he eyes his world gently with the mind of a poet. His own genesis is vague, washed over by the sands of time like so many drifts of snow. The seasons demand from him enough effort that his primary concern is not dynamism, but the simple freedom to crack mild jokes and sip coffee at the fireside, surveying the modest and sturdy gains which his labors have afforded him. There is an elemental quality to the place and her people, for the land is not forgiving, and the Canadian himself is in some ways more natural, more essential, more earthy than the American. For the Yankee man views his circumstances as temporary; the land around him is like sand in a sandbox, it is to be mastered and moved as his whims dictate. Even those Americans who've adopted a deep and somewhat antiquarian sense of rootedness in their land merely awakened there after their forebears made mad sojourns out into the primeval wastes in search of profit, or souls, or solace. To them, their rootedness is without continuity except in the future, and at that, it is a dislocated thing, for in America any notion that embraces humanity and rootedness over and against entrepreneurial chutzpah is vaguely alien.

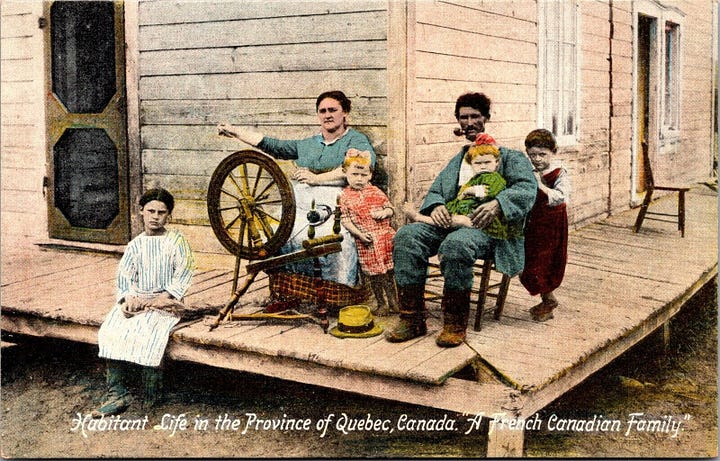

As compared with the American Revolution, the Confederation of the first ten Canadian provinces seems to me to have been a rather sleepy-eyed affair; an agreement struck by a handful of distant men who had decidedly perfunctory visions. It is as if the Fathers of Confederation all declared to one another in mild tones, "perhaps we should tidy things up around here and have a proper country." While the Laurentian elite forged a new government out of the odd bits of colonial North America, it made no difference to a French Canadian voyageur — on July 1st, 1867, he'd be eating bannock and bacon in the bush, just as he'd done the day before. He might not learn about his new citizenship for months or even years. The lives of governments and the lives of their constituent peoples are quite often entirely different animals — they are seldom synonymous.

While I cannot prentend to be any scholar of Canada, and must offer the disclaimer that all of my reflections on the Dominion are subject to critique by actual Canadians, my boyhood fascination with the country has persisted for all my life. As a teenager I dreamed to reside there, out in the outports of Newfoundland or in Nova Scotia, wandering up into northern British Columbia and the Yukon. I sought the essential Canada, the deep expressions of her people and culture — however randomly they'd been sewn together by Confederation. That she is a nation foreign to my own goes without saying; for as I hitchhiked across New Brunswick and wandered around Quebec and Ontario, I gathered that I was very much not in America.

True — if you blur your eyes a bit you could deceive yourself that you are merely in an America where things are only slightly different. But as one interfaces with real Canada and her citizens, they may find after any amount of time in Les Etats Unis that a trip to Canada feels like a vacation from a country that is really a factory. In America everyone is either busy or a failure. They are sprinting madly or they are degenerating. Everything is a vaguely harrowing sort of binary; the State of Arizona is either strip malls or divinely beautiful wilderness — the State of West Virginia is either misty mountains or savagely overturned gashes of strip-mined earth. In Canada, it can feel as if everything is a bit softer; as if one can catch their breath and dwell on every thought a bit longer.

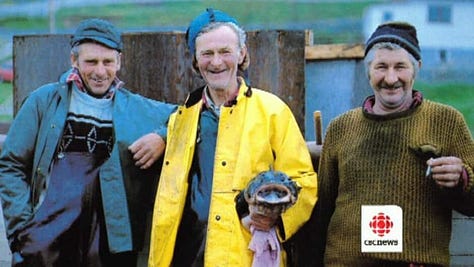

And Canadians themselves have, to my eye, proven themselves to be leagues friendlier than the vast majority of Americans. None could testify to this fact so well as a hitchhiker could. Traveling by thumb through America is, with a few notable exceptions, an exercise in penance. Penniless wanderers in my country open themselves up to unending scorn and abuse; they are quite nearly hunted as fugitives in many regions. While my tenure as a vagabond in Canada has thus far been short, the weeks I traveled there were some of the most heartwarming of all my years as a hitchhiker. Everywhere, I was having friendly conversations; I was invited into the homes of New Brunswick loggers and fishing boat mechanics, offered beers by smiling old veterans, stuffed with homemade cookies by jolly old ladies in Saint John's. In Miramichi a policeman gave me a ride and bought me a cup of coffee, chatting as if we were old friends. And in Montreal, when strangers spoke to me — which seemed oftener than in any major American city — they looked me in the eyes, deeply laughing when they laughed, smiling smiles that seemed not at all feigned. While I have long known that Canada is no utopia in a general sense, as goes friendliness she knows no match on this side of the border.

Upon returning to the States, my heart fluttered as if in crisis — I immediately missed Canada dearly and have missed her ever since. For as I crossed the border and forged southward, the lifelessness of men was palpable, and I again knew what many earnest traveling Americans know — that if you wish to find warmth and humanity, you must look far and wide, traveling between the few small flecks of friendly America that exist. Many American readers will bristle at the notion that we are not a friendly people, citing our quaint towns and hinterlands where "everybody knows everybody". But this friendliness is only known to those who match a certain idea of what a man should be — for in America, we are always sizing each other up on the binary; we are always calculating a man by his words and appearance and speech to discern whether he is a success. Our caste system is scornfully tense to all but those who keep the apperance of Brahminlike prosperity as it is locally understood. If a society is to be judged by how they treat the least and lowest, Canada — or at least New Brunswick and Quebec — has us tragically defeated.

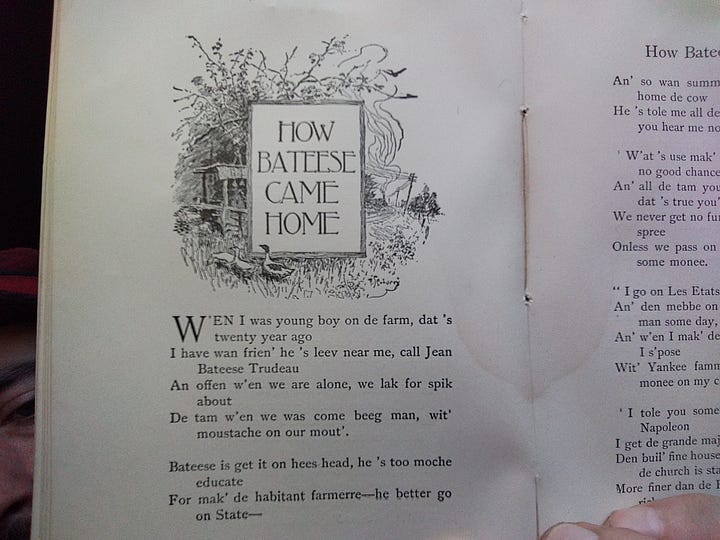

All of this is to preface a poem by William Henry Drummond, a Canadian poet of great renown who passed away in 1907 — when Confederation was only fifty years old. I had the great fortune of purchasing an unblemished 1910 edition of his book Habitant and Other French Canadian Poems from an antique store in Massena, NY for $1. In most of these poems, he's attempted to recreate the patois of French-Canadian English as realistically as possible, intermingling occasional French words and Quebecois pronounciations of English words to craft a beautifully endearing portrait of the French-Canadian habitants — peasant farmers in the hinterlands of the Province's early days. Of particular interest to me here is a poem titled "How Bateese Came Home" — it is the story of how a young habitant farmer boy dreams to go to the United States for a chance at getting rich. Having grown up in the farm country around Rivière-Du-Loup, Quebec, he strikes out for Central Falls, Rhode Island, saying:

W'at's use mak' foolish on de farm ? dere 's no good chances lef' An' all de tam you be poor man --- you know dat 's true you'se'f; We never get no fun at all --- don't never go on spree Onless we pass on 'noder place, an' mak' it some monee I go to Les Etats Unis, I go dere right away An' mebbe on ten-twelve year, I be riche man some day, An' w'en I mak' de large fortune, I come back I s'pose Wit' Yankee famme from off de State, an' monee on my clothes

It should be noted that Drummond emphatically stated that his attempt at rendering the Quebecois patois is done lovingly and without any sneer against them. In reading the volume myself, I find he has protrayed them in a most congenial manner and totally in the spirit of fraternal warmth; some of his poems even seem to yearn for peace between "de French an' de Englishman". But the writing style is at times difficult to read, perhaps most especially for those unfamiliar with the accented manner in which the Quebecois speak English. And so I've read the poem here:

And so it was that the penniless Bateese "come off de State," declaring "Kebeck she's good enough for me — hooraw pour Canadaw". I find this work titillating not only from a literary perspective — the poem is a thrill to read again and again — but as an artifact of a major difference that seems to separate the Canadian people from their southern brothers. The declaration "she's good enough for me" is one of profound humility and simplicity; it is an acknowledgement of the very human sufficiency of the Canadian ideal. Far from being an arena where "get rich or die trying" is the word, the good Bateese absconds homeward to Canada on a freight train, decidedly contented with his lot as a poor habitant farmer — so much so that "he's cry lak beeg bebe, 'Ba j'eux rester ici [I'll stay here]."

Yet unlike Bateese, us Americans are trapped in the thunderdome — any homeward departure from the Coloseum of wealth-seeking would strike as repugnant and dishonorable; the American must either accept his status as a sluggard or continue the harrying ascent to affluence and a narrow, tiring sense of "greatness". Favoring neither in my own life, I find the walk with Bateese refreshing — for I often enough wish I could make the same homeward trip; and yet there is none for me that is so natural as was his.

While I'll not comment on the present political realities of Canada — I'll leave that to my Canadian friend

— I will remark that the romantic world of Bateese may only exist in here-and-there pockets in present-day Canada. Perhaps by now his is merely an ideal memory of bygone days and little more — but I get the sense that the old soft sufficiency and contentment of Canadian life cannot be totally dead, owing to the striking hospitality and good cheer I received in amplitude in my travels there. Moreover, I cannot evade the strong conviction that if it is not dead — it must be preserved. For the Western world is, by all I know, plagued with an inhuman quality; the old congenial friendliness of Western nations around the world seems to be weakening. Perhaps our technological developments have smote us; perhaps the mad rush for innovation, wealth, and novelty has dampened our ability to revel in the simple moments of home and to treat even the poor stranger as a friend. Whatever the exact shape of these shifts in our various cultures — I suspect that some antidote to it does exist among our northern friends, and that we could learn more from them than most Americans realize. I have the hope that all is not lost, not only in Canada but in my own country too — 'Ba j'eux rester ici!

As an American living in Canada for the last three decades, this was an enjoyable read, Andy. To me, Canada was a country that "worked" really well and just made sense—at least up until about seven years ago, when the cracks that had existed widened into fissures. Globalism weighs heavily on us here now as well, and all that was "good and green" seems increasingly at risk.

A snippet from Missives from the Edge, where I (newly) write about some of my experience here on the Canadian Pacific Rim, as well as other "edges":

"There is something unique to having lived here on the edge of the Pacific, in Vancouver, British Columbia for the last three-and-a-half decades. I fit with old Vancouver’s crunchy-con vibe, its green-loving altruism, its innovative and multicultural roots. However, there is a growing unease inside me that Vancouver has passed its halcyon days, and is now entering a new twilight. Its overcrowding, homelessness, expanding inter-ethnic violence and growing reputation as a playland for the rich are just a couple of the symptoms of this new twilight that I see. And I see Vancouver as very much on the forefront of where most of the world is heading."

Still, as someone who shares your love of things northern, your assessment of "the Canada that was" seems spot-on.

Andy, I will return to this and re-read it again, to better articulate my own thoughts on what you got right and what you got wrong here. Romanticism is fun and all, but I doubt very highly in your hitch-hiking missions through Quebec and The Maritimes that you ever were rescued from the penance of an on-ramp by a member of the Laurentide Elite, that same ghoulish caste who raised a bastard son of Cuba to drive us into penury and damnation.

Canada, like America, has its own dynamisms within society and culture, tempered as they are by loyalty to inertia born in Europe. Your notions of the place remind me of my youthful patriotism and joy of coming from such a beautiful place full of awesome people.

The cloud up north also clouds my judgement, yet, more to come later.

Thanks for writing this.