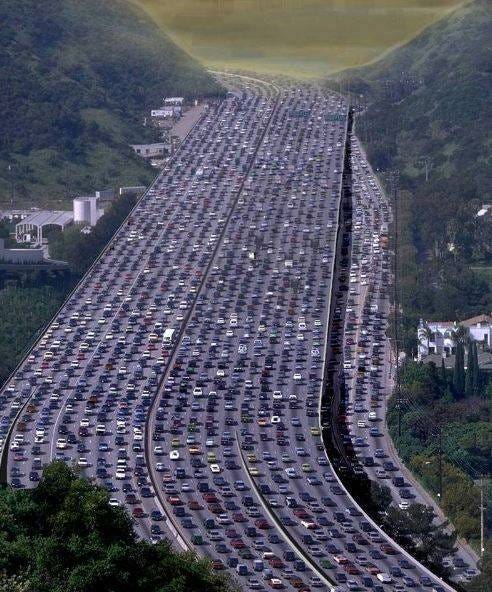

Imagine nuking Burlington once a year. Forty-four thousand human beings — men, women, and children — all immolated in a single blast of death, not merely once, but annually, as a sort of evil ritual. It is a disgusting thought. Yet the same number of Americans perished last year in automotive accidents. This is the definition of an externality in economics.

Anyone who has ever been in a near-fatal car crash knows the terror and cannot forget it. The smell of gunpowder as the airbags deploy, the crunch of metal that has inconceivably penetrated into the livingroom-like atmosphere of an automobile in transit. Cars are not merely machines, but an extension of the home. They carry with them all of the comforts of one’s evening chair or sofa out into an otherwise mind-melting world of dangers, speeding devilishly along across potholes and through violent sleets, having close encounters between speeding 80,000-pound trucks on the interstate. The experience of driving in an automobile has been manufactured to distract all passengers from the bleak realities of the American road — skin vaporizes against pavement, after all, at a mere thirty miles per hour.

Yet these machines are necessary, we are told — critical, in fact. We simply must have them. This smirking half-truth fails to reflect the reality that the world as we know it has been sculpted by the policy decisions of industry handmaidens in the highest corridors of national power. The America we know was designed to functionally require extensive automobile use in all but a handful of major metropolises. To live in rural America sans auto is to corner oneself into obscurity, to fade into senseless irrelevance — the stubborn non-driver in America’s hinterlands is a non-entity, a dropout. Some would even say that he is a loser — a word deployed as a form of stiff social policing by the same people who rhapsodize about the virtues of ‘American freedom’.

And so our yeomen race onto the road. At the age of sixteen, the madness begins. To give a child an automobile is to give him “freedom”, or so I’ve heard it said.

I distinctly remember the moment I decided I wouldn’t get a license. I was fifteen. It was June — nearly the summertime — and we were about to head to the bus on a Friday afternoon. My compatriot was a normal kid who lived in the village down the way from the school. He aired his lamentation; “Boy, I really wish I didn’t have to work this weekend.” I replied, “You are sixteen — why bother working? Might as well enjoy being a kid while you can.”

“Well, I’ve got to work to pay off this truck my dad sold me,” he said. I asked whyever he bothered owning a truck — I’d gotten on just fine with a bicycle and lived in a considerably more rural area than he did. Without a hint of irony, he simply said:

“I’ve got to have a truck if I’m going to get to work.”

And so he was off to the races, paying egregious fees for insurance, anxiously watching the prices at the gas pump rise, hoping to heaven he’d not see that damned check engine light come on again. Speeding down the road like a demon, he’d eye the bushes for the police like a paranoiac, and during the snowfall he’d spin and careen on the ice, hoping for a guardrail whenever he went off the road. In deer season, he’d leer out the windshield, half-mad with fear that a big buck would cost him a thousand bucks or more. If he needed a new car, he’d pay big-time for it, going into debt, flailing about in a great fright about getting it to pass inspection — and groveling before obese bureacurats at the local DMV office to overlook his paperwork mistakes. In heavy traffic, he’d dodge drunk lunatics in big trucks and motorcyclists with a death-wish, and eventually he’d see one of his close friends paralyzed for life in a car accident. If he had the misfortune to drive on the Thruway and forget to pay the toll, the DMV might suspend his license — and if he went to work anyway (to pay for his car and his fines), he might wind up arrested by law officers with pistols drawn.

Nonetheless, as he drove, he certainly might’ve cranked up those old country songs about the “Freedom of the Road” whenever they came on, really believing in them, never once considering the distinct air of irrational tyranny that inheres in contemporary automotive culture. And he, like those before him, would harshly judge any man who, in his own American freedom, chose not to own an automobile.

Meanwhile, I walked. The morning would always begin with lacing up my boots at my bedside, wandering out into the world to hear Creation speak. Cloaked beneath a raincoat and broad-brimmed hat, the sermons of the doves and sparrows recalled Saint Francis of Assisi, and I’d find myself at the river. My hamlet was and remains a rusticated old habitation, squalid at the edges and yet still teeming with all the antiquarian charm of an old canal town. And along the defunct canal, I’d sing to myself in peaceful solitude, making litanies to the rainy arrival of the spring.

It’d be years before I got a license, and I’d do so only under the direct orders of my superiors in the US Military, capitulating solely to fulfill my duty as an enlistedman. It brought me no joy and cost me many thousands of wasted dollars.

For the manner in which one travels builds the architecture of both mind and spirit. The delirious whizzing of the automobile tricks man — who is really a humble creature built for a stroll — into believing he is a god. As he presses the accelerator he blasphemes, and the almost violent belligerance with which he defends his precious machine is really an expression of his status as an idolater — a worshipper of the black, flaming underground lakes of oil. Perhaps they issue from Gehenna. Perhaps the combustion of this “lake of fire” has made for us a deal with the devil, and the twentieth century to now has ushered in an era of demons loosed by our senseless self-worship in the seats of our sedans and trucks.

None can be judged for this but the architects of the era — the ones who ensured our governments would decimate funding for public transit, the ones who waged war for oil, the ones who signed off on so many of the inane and humiliating policies found within the EPA and the DMV. The everyday driver is merely a dupe; an unwitting servant of the demons who rose from the oil-well. He pulls off onto the roadside for a hike, and after a mile or two, says, inwardly — “why do I feel so good when I take a nice hike!?” He visits old-time villages in New England or provincial France and inquires into why they are so much more beautiful than suburban Dallas or Tacoma, vaguely unaware that their beauty issues from the human-ness of places built for a good walk.

And so it is that I continue to be an exponent of walking. So much so that I shall build my life around it, not only as a mechanism by which to save money but as a spiritual practice. To travel slowly and without expense or complicated machinery is to praise God — to know Him, to make every day a pilgrimage. It is to deny the tyrannical control of the will that the authorities shove onto the motorist, and to lessen one’s attachment to the systems made my mere men. I will walk, and walk, and walk, strengthening body and heart, that I may coast into old age with lightness in my heart — and nary a traffic ticket or car insurance policy in my name.

Let's turn all our cars into playhouses for our kids!!!

I, too dependent on cars though I am, think often of this passage from C.S. Lewis's Surprised by Joy: "The deadly power of rushing about wherever I pleased had not been given me. I measured distances by the standard of man, man walking on his two feet, not by the standard of the internal combustion engine. I had not been allowed to deflower the very idea of distance; in returned I possessed 'infinite riches' in what would have been to motorists 'a little room.' The truest and most horrible claim made for modern transport is that it 'annihilates space.' It does. It annihilates one of the most glorious gifts we have been given. It is a vile inflation which lowers the value of distance, so that a modern boy travels a hundred miles with less sense of liberation and pilgrimage and adventures than his grandfather got from travelling ten. Of course if a man hates space and wants it to be annihilated, that is another matter. Why not creep into his coffin at once? There is little enough space there."