Years ago, when I was a greenhorn hitchhiker, I slept under the stars. For five years the open air was my bedroom, and often enough I didn’t even bother erecting a tent. I’d lay out in the steppe-like regions of the American west to catch some rest, and most of the time I had no problems whatsoever.

However, there were a handful of nights when I learned the hard way why campsite selection matters. On Arizonan arroyos, the earth seemed to be dry for months at a time — until it began to rain, and I woke to the unpleasant sensation of being surrounded by swiftly-moving water, realizing my rucksack and camping gear were not only soaking wet but actually floating away. On my first night on the beaches Oregon, my ignorance as a lifelong inlander was made painfully apparent when the tides came in and a crashing wave waterboarded me awake. Other times, the elements didn’t get the best of me — human beings did. Arriving late at night, I might bed down in what I thought was a field but turned out to be someone’s yard. In every case, a bit of know-how and research might’ve spared me some difficulty.

As in camping, the erection of a cabin or other dwelling demands almost innumerable considerations regarding the site. This is true even if one builds legally on land they own. In the case of the illegal cabin-builder, these considerations are multiplied. Not only must he make all of the conventional allowances for drainage and frost and for falling limbs and floods — he must also take every conceivable measure to avoid detection for years at a time. Therefore, before even considering the ‘micro-scale’ elements of a given cabin site, he must make a few ‘macro-level’ notes about where to build. Foremost among these is that of the legal status of the land on which he builds.

For while the illegality of constructing a secret cabin is part of the allure, anyone with a desire to run afoul of the law must do so nimbly and with an artistic fluourish. The intelligent outlaw does not brashly insist upon doing as he pleases just anywhere — he gingerly situates himself in a niche in space-time where he may go as unbothered as an aristocrat, free to enjoy his efforts as a rogue cabinwright for years to come.

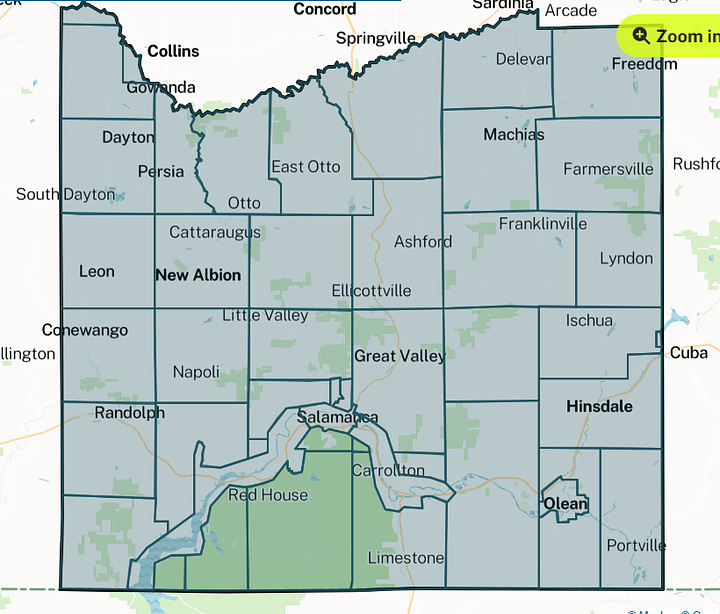

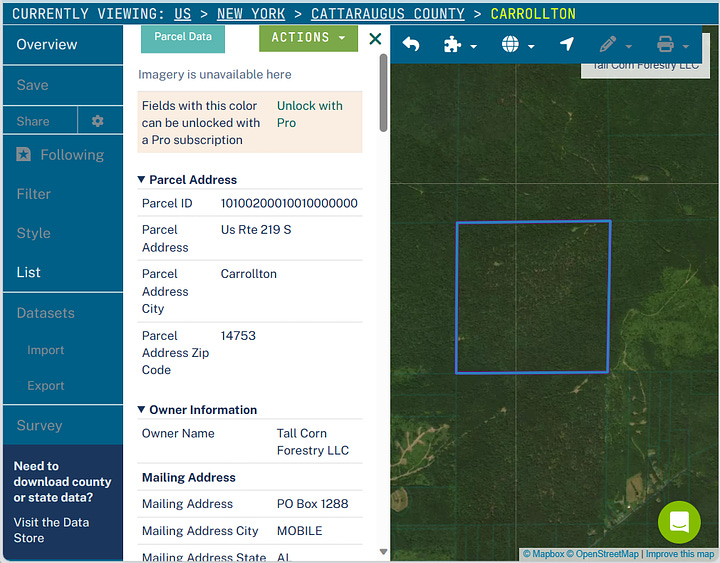

The simplest way to do this is to take consideration of who owns the land you’re building on. Numerous ‘genres’ of seldom-visited land exist where the odds of detection and eviction can be quite low. In order to do the preliminary research, one must find out who owns parcels in their target area. For this, numerous tools exist online, including Acrevalue, GridX, and Regrid. Because it is currently free to use on a laptop, I prefer Regrid. This webapp displays approximate lot lines with annually-updated information about parcel owners and acreage. Simply hone into your target area and begin a search to see:

Here, we have a 361.136 acre parcel owned by Tall Corn Forestry LLC, a company from Alabama, in Carollton, NY. The parcel is “landlocked”, meaning there is no vehicular access to the property unless there is some kind of deeded access or “gentleman’s agreement” giving the company the right to pass through adjacent properties for access. It is likely that it is logged now and again, and for this reason, it is not a good area to establish a cabin in — I am merely using this information as an example to demonstrate how Regrid works.

Perhaps most often, parcels are not owned by companies but by individuals. Usually they are locals — occasionally they are out-of-state residents (as shown by tax address records both on Regrid and in the local tax rolls). Some are investors, land trusts, or even deceased. Properties caught up in estates may be in the process of being transferred to next-of-kin — but a Google search can often tell you whether the next-of-kin live in-state or not. A bit of sleuthing can usually provide some information about the owner, trustee, or inheritor. The goal is to find properties with some of the following characteristics:

Land-locked. Properties with no legal road access are best, as they are low-value and often cannot be accessed but by walking — or in some cases, cannot be accessed at all. This generally means the property is rarely visited, if ever.

Owned by out-of-state parties (or due to be inherited by out-of-state next-of-kin). Those who live far from a land-locked parcel are even less likely to ever visit the property and may own it solely for investment reasons.

On a waterway. Waterways are almost de facto common land in the United States (though a recent SCOTUS decision does complicate this). When a landlocked property is situated on a public waterway, this means walk-in access is possible along the stream-bed without raising the hackles of adjacent landowners.

Adjacent to public land. State forests are generally legal for hiking 24/7, 365 days a year. This means walk-in access to adjoining lots is legal and simple.

Owned by individuals who are elderly. These factors further increase the chances that no one will access the property, as one must be relatively physically fit to wander roadless parts of the forest.

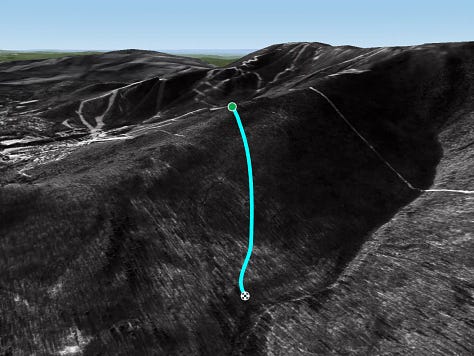

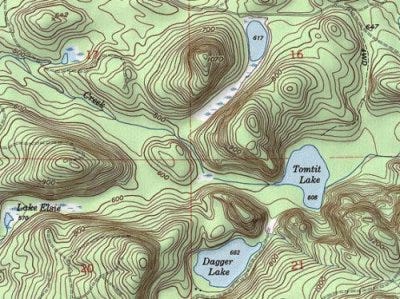

Situated on rough terrain. Goat slope, cliffs, steep ravines, and miles-long swamps and bogs are unlikely to be transited even by the most avid hunters. Use USGS interactive topographical maps for detailed topography data.

Possibly “un-owned”. Some parcels can enter a sort of legal ‘zombie’ state where they are so low-value relative to the local property tax rate that they were abandoned. If they were abandoned prior to the enactment of the local tax auction process, they may be totally forgotten.

As you research along these lines, compile a list of prospective properties, including maps, acreage, owner address, and any information you can discern about the owner from searching Google and social media sites. Sometimes, for those who aren’t wed to the idea of a ‘secret’ cabin, owners can be coaxed into making agreements with locals for the use of their property. They may even offer to sell at generous rates. I have known people who’ve successfully sent letters to property owners after careful research and found them amenable to the establishment of a hermitage on their property. This is a classic case where asking may only benefit you if you have a high degree of confidence you’d get a “yes” — a “no” may result in increased vigilance against trespassers and send you back to the drawing board.

It should also be said that when numerous properies that roughly match the description above are abutting one another in remote areas with rough terrain, they are likely un-surveyed — and situating a cabin at a confluence of chaotic lot lines can be to your benefit. The ambiguity of such areas can afford the illegal cabin builder some recourse in the event of detection if those who detect can’t tell whether he’s even on their property or not. Ambiguity almost always benefits the forest hermit.

I have almost always found the method I’ve described here to offer a solid starting point for seeking locations where one could remain un-detected for years at a time. Both next week and the week following, I’ll get into some of the more granular physical details of site selection.

Can you do a section on getting water/water purification?

How hard is it to create a well? What sorts of water sources can be trusted? Primitive water filtration methods?

Underrated series