If you’d ever like to receive a lot of hate mail, praise the practice of squatting on the internet. Though ‘adverse possession’ by occupancy is indeed the law of the land in all fifty states, it is a law that is widely hated by many landlords and property owners. This makes sense — such laws can easily be exploited by morally-bankrupt renters and are now and again cited as a means to refuse eviction many months after non-payment of rent. And certainly, there are cases of crafty scammers abusing these laws to take legal ownership of vacation homes, half-finished estates, and even multi-million-dollar real estate in the most extreme cases. The mere possibility of falling prey to these types of squatters has kept a great many locksmiths, CCTV technicians, lawyers, and property caretakers in business for many years — and has produced a lot of paranoia and expense for some of the landed gentry. This paranoia and irritation is on full display in my inbox whenever I’ve made it clear that I am not anti-squatting. Hell — I’d squat a house or land myself if it suited me, for there are many cases where my doing such a thing wouldn’t just benefit me but would constitute the best use of otherwise vacant property. I’d even consider it patriotic to do a thing like that.

But I do not advocate squatting carte blanche. Like any moral grey area, there are ambiguities that dishonest individuals occasionally exploit — and contrawise, there are overreactions that act as absurd obstacles to honest people with good intentions. I would argue that our nation’s adverse possession laws can serve crafty and hardworking folks quite well, and offer penniless families opportunities akin to the homestead laws of the old West. I would even go so far as to say that some forms of squatting ought to be encouraged. Adverse possession can unite unproductive land with productive people, no matter their assets or income. And let us not forget the critical truth that the United States was at least partially established by squatters. Even good old Davy Crockett had been a squatter — but that didn’t stop him from becoming a Congressman for the State of Tennessee.

When I contemplate how our country benefits from vast allotments of unproductive land and empty housing, I draw a blank. Unlike money or personal property, land is at once innately scarce and yet occupies a tremendous amount of physical space — in fact, it is physical space itself. It is the source of life in the form of agriculture, the source of lumber in the form of timberland, and almost every American lays down to sleep at night on dry land. Those who sleep aboard boats generally dream of making landfall, and those without a piece of land on which to dwell pine for one. The moment that diligent and hardworking hands lay claim to a piece of overgrown acreage or to a rusty fixer-upper home, those hands and the soul within them not only feel a sense of purpose but lead a man to beautify our country and expound on its wealth. Such a thing as this is leagues more important than the ability of a class of distant and geriatric owners and their numerous holding corporations to hoard millions of acres of vacant land whose contribution to this nation consists of dry numbers on an Excel spreadsheet.

Therefore I say unproductive land ought to be viewed as a national tragedy wherever it exists. Let me be clear and stipulate that by ‘unproductive’ I do not mean ‘economically profitable’ per se. For a dismal swamp is of greater value with a sturdy layabout dwelling within its reaches and ekeing out an eccentric existence amid the larches and pines. The rocky goat-slope wasteland is adorned by rock-toothed cacklers and their barefoot children, and our riverine plains look better with boat-dwelling madmen and crank preachers taking stead on rusty barges. The types of men who are drawn to the strange and inaccessible margins of our natural beauty are often feverish exponents of the American cultural legacy whether they know it or not. Hermits, moonshiners, spruce-gummers, and moon-eyed families out in the harsh slate hills must be defended at all costs and given freedom to roam and settle on any land that sits idle. Icing them out with a harpy-ish sense of bureaucratized ‘justice’ issues a nasty strike against the American mythos.

Some years ago I examined the tax maps for my county, looking up lot lines and parcel ID numbers in the tax rolls. I was curious to see who owned what land and to discern what they might be doing with it. What I found shocked me — out-of-state investors (as individuals or LLCs) had purchased large tracts in my town, often in areas so inaccessible they could never be logged. Other tracts were owned by dead men, and a simple Google search of their next-of-kin found all of their children to be living in Florida or Carolina. Still others bumbled through the awkward and slow bureaucracy of the ‘tax sale’ system, unpaid taxes piling up on all of them, with few exthusiastic takers for these landlocked and double-landlocked parcels with no legal access. Some of these seemed effectively forgotten — abandoned long before the tax auction process or digital mapping reigned, registering eerie parcel ID numbers like “999.999-9-9” and “null” or “no data” in County records systems.

I shamelessly trespassed on a few of them some years ago in search of any sign of human visitation or improvement. On each, virtually none was found, and the few signs I did see pointed to near-total abandonment for at least forty years — rusted beer cans of the 1970’s style or earlier, car parts from WWII, or in most cases nothing at all. Completely vacant land, raw and in total disuse, the forest in a state of primeval dereliction and mis-management largely in areas where vehicular access was dubious at best. While I enjoyed skulking about in these unknown territories, I couldn’t help but find it heartbreaking that they’d been so totally neglected — that such magestic wilderness would be reduced to mere abstracts and conveyances for investors who likely had never set foot in my beloved town.

But more heartbreaking than this is the reality that an entire generation of local young couples are being stonewalled out of finding suitable homes or home-sites. Homes that sold for $40,000 in 2006 now sell well above $110,000. Fixer-uppers that would’ve gone to market for the value of a used car now linger and rot on the ledgers of realtors and banks — and the bureaucratic turnover before they’ll ever be sold is so long the eaves of their roofs will cave in under the snow before they go to auction. Young men labor diligently at securing down payment sums for mortgages, only to watch rates rise and inventory shrink — and to realize that they’ll need to save more still. I see families delaying in having children, couples delaying marriage, and many young people abandoning all hope of ever owning property. Meanwhile, the men who own vast quadrants of our township are doddering in their chairs of suede, sipping from fat University pensions, only dimly aware that their financial advisors have stuffed away some of their wealth in “investment acreage” in some distant backwater.

One thinks of Ezra Pound here, of his “Canto XLV”, excerpted here —

With usura the line grows thick

with usura is no clear demarcation

and no man can find site for his dwelling.

Stonecutter is kept from his stone

weaver is kept from his loom

WITH USURA

wool comes not to market

sheep bringeth no gain with usura

[...]

Usura slayeth the child in the womb

It stayeth the young man’s courting

It hath brought palsey to bed, lyeth

between the young bride and her bridegroom

CONTRA NATURAMIt is the “site for man’s dwelling” and for his “house of stone” that the squatter dares to secure by his own wit and cunning. Yes — there are squatters who are entirely without style, who are living as animals might and savagely ripping away at the fruits of the labor of others, and I will never defend them not because they have taken their ugly stab against the sacred cow of ‘private property’ but because their acts lack all style or edifying ambition. These rapscallions ought not to cloud the practice of taking stead on forlorn hills and in the creaking, deathly husks of farmhouses. Strong bucks of men who gingerly revive some lacklustre real estate are heroes; they see a wrong and right it not merely for their own benefit but to psychically secure the mythological power of the American homestead. They may act as men who are born of the land and wed to their towns, who stand aright over and against the machinations of faraway usurers. Sadly, it is the same valiant sorts of men who most often adhere to whatever flavor of morality prevails, and do so doggedly — and in our present times, squatting is seen as a seedy practice. I submit that this ought to change.

Any measure that can be taken to penalize real estate speculation is a damned good one. The decades-fallow field ought to sting its owner like a viper — the empty cottage should be a thorn in its title-holder’s side until it is filled. At the risk of sounding like some kind of Marxist, I must state unequivocally that the bourgeois morality that tells a young man he must wait patiently for incremental legislative change in order to secure site for his own dwelling is disgusting and benefits only a handful of owners. Over and against this paltry and dessicated mindset, young men and their families would do far better to begin taking adverse possession of derelict properties here and now — during their most fertile years — than to doom-scroll Zillow and waste away into their thirties. This is possible in the present legal climate and hindered only by the morality of the dullard and the harpy that would tell us that squatting is ‘immoral’ and should be ‘banned’.

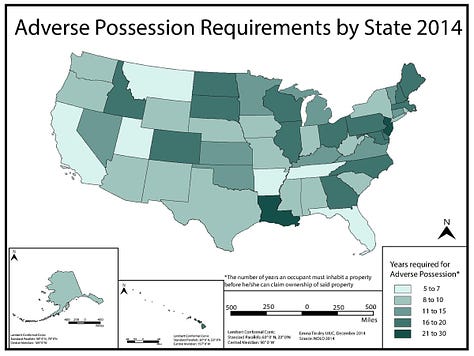

In all fifty states adverse possession laws exist. They range wildly — in Arizona, only three years of “open and notorious occupancy” can win you the title to a piece of real estate. In New Jersey, that number is thirty years. Most states, however, are between seven and twelve years of such occupancy, usually demanding a willingness to pay off the back-taxes and to produce a paper trail verifying continuous occupancy during that time. All of these matters are civil matters, not criminal — and after thirty days of continuous and provable occupancy, squatters have rights that can slow down or even functionally prevent eviction. If no one attempts to evict you within the state’s required time-frame for adverse possession, you take the title and the property is yours. The time-frame of adverse possession ought to be shortened federally, and ‘housing rights’ organizations ought to take a new tack and begin to fiercely advocate for a new generation of squatters and aim to popularize the practice.

This may appear to be my only legitimately “leftish” view. And yet the necessity for such is obvious — and nothing about the flavor of squatting I describe is remotely immoral. Nor does my advocacy of these practices stem from a communistic philosophy. To the contrary, Pope Leo XIII outlined a vision of property that is wholly in keeping with the orthodoxy of the Church in his 1913 encyclical Rerum Novarum. In essence, man was created in the image of God, and God is Creator. Therefore, man’s relationship to his own small-holding of acreage in some respect mimicks the relation between God and Creation — and can be a site of man’s mystical recollection of God’s own logic as supreme Creator. While we cannot approach the perfection of His own capacity to create, the ownership of land gives us a means to encounter some of His creative power, and we can there mirror it in our own paltry way. It is therefore reasonable to believe that any policy or legal disposition of states that is congruent with property ownership across a wide segment of men — even small-holding by as many men as possible — is consistent with the spiritual and moral health of nations and indeed, of all of Christendom.

I would not go so far as to suggest that Pope Leo XIII or the Catholic Church outright condones squatting — but I would certainly submit that the lawful mechanisms by which squatting can take place in the United States are largely congruent with a healthy moral outlook regarding property and its moral utility among men. Those who seek to defend the hoarding of un-productive land are, so far as I am concerned, opponents to innately divine purpose of land, as Created by Our Father. And so it is that I am now and shall ever be a tireless exponent of squatting — no matter how much hate-mail it generates in my inbox.

Beautiful post! We need more Christian squatters... God wants us all to share hospitality with one another, so I'm all about finding more ways to facilitate this!

Welp, I started with the wrong post. Bye bye