Incognito in Delaware

Or: The Hazards of Living in Public

I went to Delaware because I couldn’t think to go anywhere else. I didn’t want to run into anybody I knew — I didn’t want to be seen. Here, we drive by anonymous chicken-sheds along slow-speed byways en route to deeply-private hedgerow-fenced condos; as I stepped up to the third floor apartment, I heard the ocean crashing down below me. I shut the shades; I took the battery out of my cellphone. Nobody knows where I am — and nobody will recognize me here.

Standing silent on the balcony, the clean, crystalline lines of the oceanic horizon soothe me. Today I have no viral Tweets. I am not reading any ‘hot takes.’ There are no death threats in my inbox. And I have not a single obligation looming over me for at least four months.

This is the moment I have been waiting for for a long time, though I have waited without understanding just what it was I was waiting for. Standing wordlessly in this undisclosed location, deep in a neat, orderly, mostly-geriatric kind of terra incognita by the sea, I am reminded of what life was like for me before I got on the internet. A distant, fugueish memory of the time before I had any kind of a public profile sweeps over me — a memory of a time when I was always anonymous, unseen, obscure, and therefore free to do and say as I liked without so much as a word of running commentary on how I think and live. It was a wholesome and freewheeling time.

Now, those days feel far behind me. About 65,000 people watch everything I do. They expect me to be present online daily; continuously publishing my opinions, snippets from my life, theses on important issues, ‘influencing’ the ‘discourse’ with my ‘content’. And where once, 65,000 sets of eyes might’ve turned toward a single man once in a great while at most — even if he were a King or a truly famous musician, speaker, writer, etc — these days, the “watching” is not concentrated into a single discrete event. Instead, it is daily, continuous, 24/7 — and deeply granular. Moreover, it is available to anyone who posts online, at any time; one may go ‘viral’ very easily and without intending to do so. And all it takes is a half-dozen viral posts to make a normal person into a niche internet celebrity.

The constant, ultra-fine, deeply granular kind of “watching” that the small-time internet celeb experiences appears to be a thing with no real anthropological precedent. And though my own audience is an incredibly tiny fraction of the audiences of far larger “content creators,” I have found that the experience of being watched online is a distinctly terrifying, exhausting, even nauseating experience. The “parasocial” relationships people have with whatever version of you they have concocted in their minds is often genuinely disturbing.

Yet it pays — so what can one do but continue it? Even on the days that I do not feel like posting anything, I post. For the checks continue to come in, paltry as they often are — and it pays to wring out the mind and spirit like a sponge for any sort of “content” that might sell.

I put that word in quotes because it is a word that I naturally despise; to call the product of one’s mind and heart mere “content” is to bypass the creative process entirely. It is to sell a kind of formless, bituminous grey matter well before it is ever formed into anything resembling ‘art’. For in the digital landscape, there is no time for art — one must keep posting, one must constantly dredge up something else to post. Like dragging bile out of an unsettled and hungry stomach, you saddle up before the keyboard and begin to type. There are no quiet moments here; one cannot take a walk along the mountain trail with one’s beloved without carrying the camera “so that you can take some pictures to post.”

This has all been documented by others with large online followings before; perhaps it is now a standard life arc — a kind of ‘hero’s journey’ amongst those who rise to any kind of notoriety online. And again, I say all of this as one with a very small audience, all things considered — and one who is ultimately grateful for the audience I have. But it is not as if I have millions of followers, and frankly, I thank God that I do not have millions of followers.

I am not joking when I say that I actually pray that I never find myself being watched by millions of human beings.

It’s heartening to know that just as I find myself running this gamut of misgivings about being an “online writer,” I see that I am not alone. Two days ago, Paul Kingsnorth — who is both a serious influence on me and a personal friend as well — posted an article entitled Going Under, Coming Up, wherein he describes both his recent physical illness and what he termed “a season of deep fatigue and burnout” in his writing career. He says:

I could say a lot about what has happened [since being baptized] - I have said a lot on this Substack - but I could also say nothing and it would perhaps mean as much. Words have their uses and their limits.

Lately, I have felt much of the same. As many of you may have noticed, I have not posted since late November. Several times since posting my last article, I have consciously thought to myself: “If only I could publish an entirely wordless article, for it might say what I wish to say far better than words would.” Having already had these thoughts lodged in my mind and heart, it feels as if reading Paul’s essay on the matter gave me permission to accept this urge towards wordlessness rather than to view is as a failure or a liability.

For though the means by which we interface here is machinic in nature, and is indeed a piece of ‘information systems technology’ characterized largely by routine and robotic repetition — the author is not a robot. A man’s soul and spirit cannot spit out tasty little treats on command at all times. Moreover, it feels pointless to call our periods of creative austerity “writer’s block” or anything like it. The daily Tweets, the weekly essays, the monthly columns — these routinized forms of writing do not have seasons; they do not have a wintertime or a hibernation. They come not as fruits of a harvest with its natural time and place — but as a mechanical milking-machine comes for the cow.

But what is the cow but a witless dullard? Her purpose is to be milked for pablum for babies and cheese fanciers and pizza-stands — she offers us only the subtlest glint of anything derived from the intellect. And even there, what we can gain from observing the cow is largely projection anyway; the cow herself is only a kind of fleshy machine for turning grass and hay into milk. Quite the same with the true “content creator,” who finds creative ways to repeat himself over and over again in saccharine tones and glossy technicolor; what with scheduled posts and a surgically-curated repertoire of images and ‘hot takes’. His agenda is to meet the machine where it’s at; who he actually is often remains obscured behind the apparatus with which he is engaged.

There are more than a few things I’d reckon Mr. Kingsnorth and I have in common, and one of them is that neither of us has much of a desire to be “content creators” who churn out recapitulations of the same old thing in an effort to increase page-views. Neither of us wishes to hide behind a tired old schtick — we share an earnest desire to bare our hearts, not as speakers in a one-way oration but as compatriots alongside our respective readerships; fumbling about in our own way, sharing our work on the hope that those who read it might find something of beauty there.

And it is simply not always possible to reduce this process into the ‘weekly edition’ model. It is a thing that by nature defies consistency at one point or another; yet this defiance is at odds with the basic structure of the internet. The monthly invoices roll in — an expectation to produce regularly is attached to the offering of regular compensation for the “product.” The tides of digital opinion ebb and flow — each day, there is some news or some happening that commands our attention and must be addressed. Solicitations for advice now and again overwhelm my inbox, and each merits an answer, though the question of when I ought to produce that answer sails off onto the deep and undending horizon of time. Meanwhile, there are bills to pay, funerals to attend, errands to be run, and a cooing baby who demands the great bulk of my attention whenever she is around (which is to say always).

From this point of view, I would quite rather do “all my future writing in hand-printed chapbooks” so as to “give them out on street corners,” as Paul said in his essay. Perhaps I could really pull such a thing off — perhaps I would not be so crazy to try it out.

In reading all this, one might wonder why I ever involved myself in any of this online writing stuff to begin with. The answer is simple: If you wish to be a ‘writer’ at all, you must be online. You must have a social media presence. Perhaps a year-and-a-half ago, a senior acquisitions editor at a “Big Five” publishing house called me on the telephone — and his first question to me was “how many followers do you have on social media?”

I was stunned that this was his first inquiry. The quality of my work seemed to be a secondary concern at best, if that. His number one interest was in ensuring to the best of his ability that I could market my own book myself. And, owing to how he yawned at my modest social media numbers at the time, I realized that I had only one real option — I had to amass a larger social media following or I’d never get a serious book deal.

Some eighteen months later, I’d find myself with over 50,000 followers on “X” and over 15,000 followers on Substack. After achieving these landmarks, I had a conversation with the man who’d become my book agent. The discussion was all normal business, and he seemed very much interested in working with me — but after we’d covered all of the major questions about my upcoming book, I asked him an off-topic question. Our dear friend Eric Brende — author of the bestselling book Better Off, which is about the year he spent with the Amish — had no social media until very recently. He’s in his sixties, and in spite of having authored a best-selling book, he told us a couple years ago that he couldn’t get a book deal.

Why? Because he had no social media.

So I asked my agent: “Would you be interested in my friend’s work?” The answer was, not shockingly, an immediate no. The agent threw his hands up and said that while he understands Eric’s conundrum, and is certainly sympathetic to his plight — you’ve just got to have a serious social media presence to get published these days. That’s just how the industry works now.

It made me wonder just how many brilliant authors there are out there with excellent manuscripts collecting dust — solely because they have not elected to stand up to be continually watched by tens of thousands of people online. Moreover, it made me understand that though posting on X feels like the most profound waste of time imaginable most of the time — the following I’d acquired there would be my sole lifeline if I was to have even the slightest chance of writing for a living ten years from now.

Owing to this, the writer is now — whether he likes it or not — a prisoner of the social internet; he must expose himself there like a lizard in a terrarium, posing for the cameras, always ready to be ogled at no matter how he feels about it. Gone are the days of mailing off one’s typewritten manuscript from their beach-hut in Baja for a chance in the limelight. Now, we must submit ourselves to the all-seeing eye first and foremost or else accept utter destitution and obscurity.

As time goes on — that ‘destitution and obscurity’ doesn’t really seem so bad.

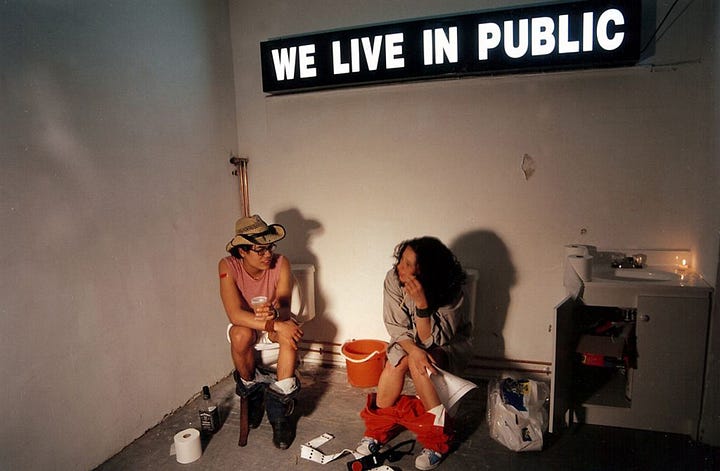

Mulling these matters over by the Atlantic as I am, I’m reminded of a 2009 documentary film by Ondi Timoner entitled We Live in Public. Though this film seems to be fairly obscure or at least seldom mentioned these days, it had a profound impact on me in college — for it was ultimately a prophetic (and avowedly dystopian) vision of “the social internet.”

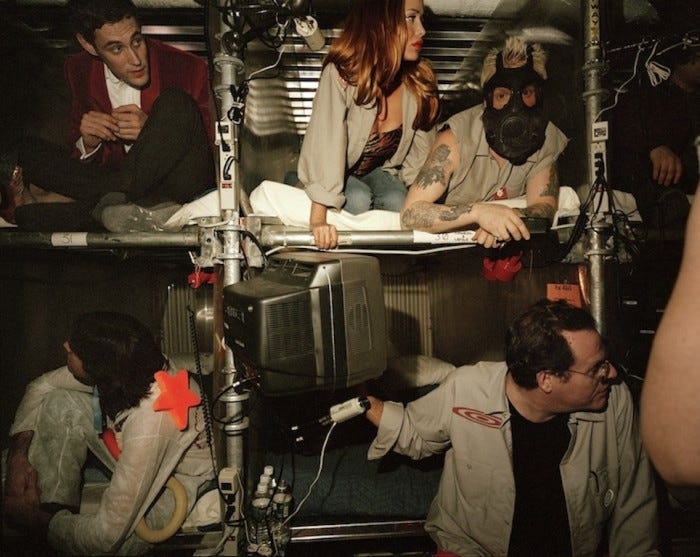

The documentary explores an especially bizarre project headed up by Dot-Com millionaire and founder of ‘pseudo.com’ Josh Harris called “Quiet: We Live in Public.” The project consisted of placing one-hundred people into a large New York City warehouse space that was outfitted with webcams in practically every corner — even to include the toilets, the bedrooms, and every living area.

There was nowhere in the entire facility that wasn’t being livestreamed; and all participants agreed that they would remain in the building for 100 days. Participation was free, and in fact, those who had entered the building could get whatever they requested — be it food, booze, or even drugs.

In the beginning of the experiment, the atmosphere was charged with the raucous spirit of the Dot Com era. The year was 1999. Party people and exhibitionists packed into the underground apartments as the cameras were wired up for full-time 24/7 streaming. Thousands of people worldwide logged in to watch an apocalyptic orgy of live sex, drinking, partying, and mayhem of a flavor that could only have been produced in the year 1999.

But within a couple of weeks of insanity — even the most enthusiastic participants began to come apart at the seams. With nerves frayed, no sunlight, and not so much as a single moment of privacy during day-to-day life, a kind of madness swept over the underground bunker. People began to fight; some slunk into a dark depression — others had panic attacks live in front of the cameras. Finally, NYPD forced the doors open, and dozens of harried participants poured out onto the street, rubbed raw by the constant watching of the cameras.

There, in 1999 — five years before Facebook, seven years before Twitter, eleven years before Instagram, and seventeen years before Tiktok — a live preview of the social media era had already been shown to the world. Instead of taking the experiment as a prophetic warning, Timoner’s documentary won a few awards at Sundance and MOMA — and following this, Harris’ experiment mostly faded from memory entirely by the time the social internet’s delirium entered full-swing. Yet there was an obvious warning inscribed into the film; a warning that we all would’ve been wise to heed.

Instead — the money in watching has simply been too good for The Powers That Be to pass up on.

But much like the Colosseum claimed the lives of many of its performers, the new digital Colosseum we’ve constructed seems to generate burnout, mental illness, and “crashouts” amongst our “content creators” as a matter of course. Worse than this is that at this stage of the history of information — mystery is no longer an element at play. For the model of “Living in Public” demands that those who place themselves on display for the masses do so in an unbroken fashion — the collective attention span is simply too short for the wider culture to tolerate those who abscond intermittently for long and indefinite periods of time.

Yet absconding is often what one needs most to produce good and edifying art. One often may need to empty the calendar, take off, leave the telephone unanswered and the emails unchecked — but this is getting increasingly difficult to ever do. By all I can tell, this is largely because the internet cannot tolerate any regime of ‘content creation’ that is both slow and intermittent. Instead, routinized posting is rewarded; 24/7 cycles of outrage are milked for millions of views — users are algorithmically encouraged to bare more and more of the fine-grain details of their minds, bodies, and lifestyles, and to do so as often as possible.

Perhaps this has something to do with hosting fees. After all, as a website becomes more popular — that site or app will require more and more physical infrastructure. Servers will be needed, and they run on electricity; fees increase with every new score of users who log into the site. Therefore, as a site becomes more popular, it must generate more and more money if it is to make a profit. In time, every single website seems to go down the same path: toward faster, more quick-cut, outraging, granular type posts. The profitable site has its users logging in constantly, lingering long over all the posts they see, interacting at high rates — yielding metrics that are favorable to investors and advertisers alike. And to obtain those metrics, websites use many of the same psychological techniques as marketers and casino operators.

If a website or app were to adopt a slower, more intermittent model, it could not last if that site became popular — as it would struggle to finance the physical infrastructure the site would require. Substack is a prime example of this. Grateful as I am for Substack’s slower model, we see that as the site has become more popular — the owners push more and more more attention-grabbing features like reels and livestreams.

In short — for a website to stay competitive, it must hack the brain-stem. It must find a way to short-circuit the dopamine receptors in the brain. And there is no “slow and intermittent” way to do this. So we find that the natural, organic creative process in human beings is now at odds with the financial and physical infrastructure of the technological medium through which most created visual and written content is now circulated. This is a serious boondoggle for artists and writers around the world — and its default maximum state (or logical conclusion) appears to be akin to the experiment shown in the film We Live in Public.

There must, of course, be another way. Substack cannot be the final answer — for it will inevitably succumb to the same internal contradictions that turned Facebook into a ghastly AI-slop machine. Hosting costs will not go down; they will if anything increase, and sites like Substack will have to cover them by whatever means they can. The architecture of the site will, over time, be altered to become increasingly addictive — and consequently, the creative processes that are rewarded by the site will trend downward toward the ‘lower forms’ of ‘content creation.’ Already we see that shorter articles go viral more often — the attention span required to read a 5,000+ word essay is just too much to ask. Eventually, sites on this path either veer downward towards AI slop, porn, or a model that predominantly favors quick-cut “reel” style videos — or they go out of business.

Where, then, can thinking people find a durable haven? The answer is offline. That can be the only answer. Though the internet can and must play a role in facilitating offline events, advertising offline gathering spaces, or assembling snail-mail newsletter lits — for we’re all here right now, not IRL — we’d be wise to orient our activities toward the Real World. And yes, when I say “Real World,” I mean the world offline — I reject the idea that the online and offline worlds are equally real.

This is, in large part, why I am in Delaware. I needed to go somewhere that hadn’t been ‘hyped’ by the internet. I needed the least-Instagrammable place; a place that has gone largely overlooked by the all-seeing eye of the filtered selfie photograph and the TikTok reel. Here, there are septuagenarians with walkers on the beachhead. There are well-to-do DC housewives ordering the buttered scallops at the family-run seafood store. Something about the world here does not feel to be steeped in the blue light of the “smart” telephone — one gets the sense around here that nobody’s filming, that there aren’t any viral posts waiting for ‘content creators’ around every corner. It’s normal people, living with scenery that is “just OK.” And somehow, I find this very nourishing — it is the perfect place to think about what’s next.

I remain committed to opening a physical, offline, IRL social club this year. Though I’ve had to do a little soul searching after the death of my mother and the birth of our baby, I’m honing in on a vision for it. I’m seriously thinking about moving this newsletter into physical space, too — by turning it into a snail-mail affair for paying subscribers. The finer details of both the club and the snail-mail newsletter are still to be determined, but I write to tell you that I am now framing those visions up out here in Delaware.

Though I’d had a mind to go further south, and to take some kind of a wild trip across the country — we’ll see. Perhaps I won’t need to do all that. Perhaps I’ve got a vision that may offer a much-needed counterpoint to the We Live in Public model; and if I do, I will make haste to bring it into fruition come spring.

Until then, I’ll still be posting as we wander. But every post will be written less out of a desire to get you to click, interact, and subscribe — and more out of a desire to someday soon meet you in real life, offline.

Merry Christmas to you all, and Happy New Year,

A.M. Hickman

From a Quiet Beach in Delaware

You have spent years and years of your life engaged in the hard work of engineering it to fit your preferences just so. A commitment that I admire. But you have found, as nearly everyone does, that such an effort doesn’t yield the happiness they expect it to. Things aren’t just right. If only this thing was different. If only I had this. If only I didn’t have that - THEN I’d finally be satisfied.

A tale as old as time.

The way is to accept limitations as a constant. There no matter what you do. Maybe you should consider being a postman to pay the bills, and then your passion/art can be completely on your terms. In your off time, you can read and write and hand out pamphlets on the corner.

Great article; social media seems like a counterfeit to building a proper “spiritual life”, as this has been classically defined in the past.