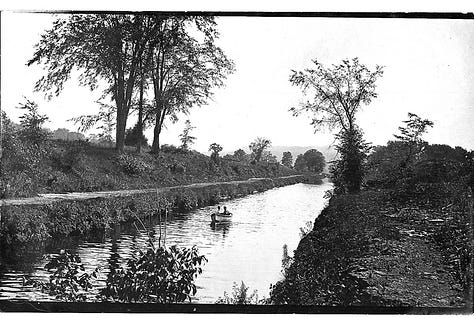

Of all the forms and flavors of abandoned infrastructure, none touch the heart quite like an abandoned canal. Earthen hummocks lazily lay in long straight lines, segmenting whole valleys and their fields. Shimmering with the unshaven briar and sumac of neglect, our waterlogged passageways of crumbled stone croak madly with peeping frogs and vibrate with hordes of mosquitoes in flight. Those who dwell along the deprecated banks of this tired old inland waterway idly let the visual state of the canal mark notches in their years; in autumn she is splayed out through the forest, losing her crowning veil of maple leaves and ferns in the chilly gales. The leaves drop one leaf at a time like memoranda from above heralding the wintertime as a lockman’s cry might at navigational season’s end in former days. And in good time the canal will freeze over with thousands of reeds quaking through the ice. All through the long, bleak winter, the canal is as empty as it likely was in its heyday winters — all the boats laid up dry, the big barns silent as if they contained scores of mules asleep in the hay. When the spring ‘breakup’ occurs and her hilled banks light off again with the green and yellow of growth and bloom, one only needs to blur their vision slightly to imagine the packetboats full of grain and drawling derelict boatmen — by summer, the buntings and stars and waving flags visit only as memories from a time we have not lived.

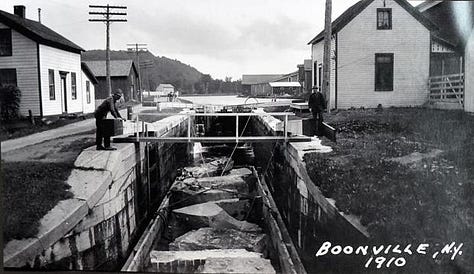

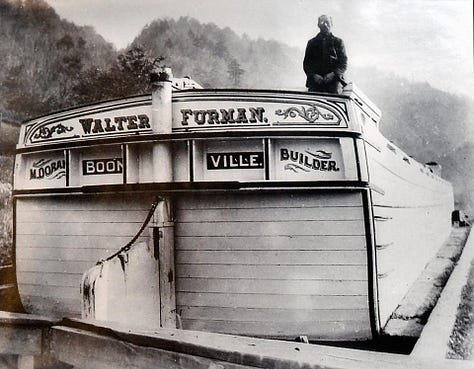

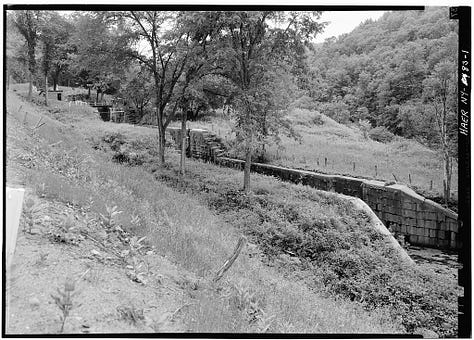

My own childhood was marked by such extreme sentimentality about the abandoned canal — ours was known as the Black River Canal. In a poetic nod to the Punic Wars, the course of its channel would begin in Rome and end in Carthage, stretching some seventy miles with a rise and fall of 1,079 feet. It was considered an engineering marvel of its time across the world — 609 feet of the waterway’s rise took place in a twenty-five-mile stretch, where seventy locks would be built. Transiting from only Rome to Boonville took days. Along the way, most locks had a full-time live-in lock-tender — a man whose sole responsibility in life consisted of maintaining and operating the canal structures that allowed the passage of boats both and up and down the course of the water. Today, many of the old ‘lockhouses’ are still standing — many are still in use as private residences.

A simple inspection of my own biography would suggest that I was born to be a ‘lock-tender man’, for these men were notoriously idle and managed to epitomize the feverish romanticism of the canal era. All day, to man one’s comfortable station, where his wife grew turnips and potatoes and his children fished — to observe the passage of every boat, yammering with the boatmen, twenty minutes at a time. All day, idly gazing out among the fields and brooks and intermittently working the locks, hearing the stories of the canallers who had hitched their mules in places as exotic and far-flung as Rome and Port Leyden. Such is the innate desire of any boy who grows up along the old canal, playing and dreaming and living among the empty and ruined locks, whose very construction seemed so unlikely as to constitute its own sort of childish fantasy.

The gift which the Black River Canal gave me was almost ontological in its form and flavor — it preserved some dreamlike vision of old America, America unmolested, un-digitized and without bureaucratic blemish, an America far preceding tollway plazas, self-checkout kiosks, and adjustable-rate mortgages. Something of the very marrow of our country was implanted into my own spirit by those strange ruins; a sense that a young man could still hitch his mules and meander with all of the bumbling poesy of his forebears. Upon departing my sleepy hamlet and walking the soil as a young man, the reality that ‘canalside America’ is now only a chimerical whisper, a barely-hanging-on notion that is alive only in the most distant and distorted ways was painful to me. It would take years of journeying to realize that such a view of my country was and continues to be only as alive as my own heart presently beats. And in time, owing almost strictly to the canal’s benevolent influence — I would be insisting on a canalman’s America, as I am today.

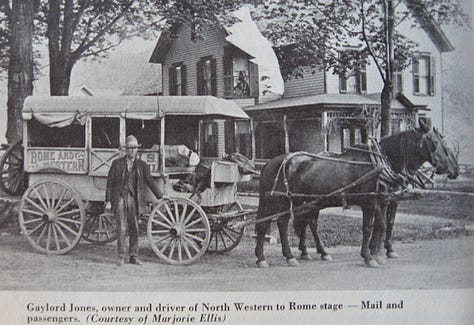

First conceived of by Governor DeWitt in 1837, it wouldn’t be fully realized until 1855 — when the stripling railroad system was in its feverish adolescence. Its heyday was gravely shortened by the railroads, which all but supplanted the waterway within the span of a couple of decades. The State never made its money back on its Black River Canal investment, and after languishing for what seemed like a lifetime, the State declared the canal formally abandoned in 1925. In time, our general storefronts and canalside hamlets would go quiet, and my home town would never again be at the center of any sort of boom. The ruined canal and the bucolic havens through which it meandered would sink into obscurity alongside so many wooden lock-gates and caved-in stone aqueducts. A strange mix of tragedy and suspended time linger alongside the incredible splendor of our surroundings — this is the land in which I grew from a boy into a man.

Yet more than a biographical note in my own life, the thicketed ruins of Black River Canal offer a worthy lesson to all Americans — that the metaphysical substrate from which our forerunners’ dreams were born is fundamentally good and beautiful. The bizarre delirium of industrial prowess and post-WWII homogeneity is not the sum total of what America is, was, and can again be. The slowness of the mule-towed barge or packet boat can set the pace of our lives and history; the guffawing of the lock-tender can and should remain a key aspiration in our professional lives, over and against an obsessive life of overtime and garrish consumption. Doubtless, any soul who feels dispirited about these United States is still free to take a ramble along the canal’s overgrown banks — and in so doing, they may find their faith in our country and its storied hinterlands restored.

So poetic! The only way a man ought to approach a chosen vocation!