I. American Reactionaries

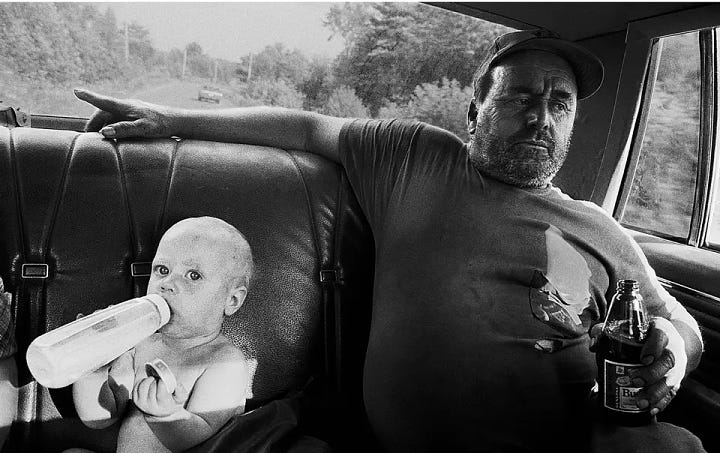

There is a quiet divide among Americans with a conservative sensibility. There seem to be those who, misguided and wracked with a certain disorder of mind and spirit, pledge allegiance to a national culture characterized by a gross and profane democracy; they blare abrasive rock and roll in their SUVS — they nibble at the hems of bald-headed nouveau-riche dimwits, barking madly about “jobs” and the next election, all while the stripling castles of the old order are razed to make way for another Hooters or Panera, another subdivision, another expression of a faceless and empty ‘democratic American culture’. These raucous neo-Reaganites urge on the complete unmooring of Western culture from its own order and logic — they hasten the total detachment of mankind from all sense of beauty and humanity. And as they carry on in this fashion, they somehow pay lip service to a vacuous sense of ‘traditionalism’. Their traditionalist pantomiming is a sort of Machiavellian bait which until recently, our nation’s provincials have gobbled with abandon.

On the other side of the divide, a medievalist tendency quietly grows in little shoots and spurts; a hearty romanticism which bleeds from the branches of the old forests and issues from the censers of traditional Priests is alive in the hearts of men. These are the sorts for whom the word ‘peasant’ contains not the slightest whiff of anything derogatory; perhaps some of them would go so far as to actually hope to become more peasant-like. Intuition governs their eye and heart; something in their gut says to simplify, to seek God, to build beauty locally in a thousand little ways. While they may not be howling Jacobites and neo-Monarchists, their essential quality hearkens to those movements. Some could say that those with this sort of a sensibility are a rarity, but I would suggest the opposite: The extreme romanticism of the feudal era seems to be awakening after five-hundred-years of violation and slander at the hands of modernist ghouls.

Indeed, images of stone houses, old barns, and Scottish fens are traded with intense gusto on Pinterest and Twitter, a fact which by itself may be of little significance. Yet the attraction to a particular flavor of beauty or fantasy is of deep psycho-spiritual import; an atheist can only remain an atheist for so long if his fixation on Cathedral architecture continues unabated — after so long, he is forced to contemplate how such incredible beauty ever came to be, he ponders it until he is in a trance, and begins to wonder at who this gentle man on the Cross actually is.

So too with those who, in replying to videos of grotesque inner-city violence reply with the phrase “I want to live on a farm.” Throughout the culture, agrarian aspirations reign — they circulate wildly, and many have made an entire ‘cottage industry’ of them. Many young men who might’ve sought great fortune at Boeing and Dow even twenty years ago today scroll through Youtube, watching hours of videos comparing Nubian goats to Boer goats, and dreaming of the wattle-and-daub cabin they might build for their beloved on some lonesome prairie. And the young women, too, are no less enthused — exhausted from the depravity of the post-sexual-revolution ‘marketplace’ which has often scarred their hearts and jilted them, they seem to be often dreaming of courtly romance, chaste betrothals, and being blessed with many children on a shimmering forest estate. The deep subconscious must register the psychological architecture of such ideas; the worldview each of them implies is entirely alien to American democracy, to rapacious economic ‘development’, and to practically every structure undergirding the modern era. From tiny houses to reclaimed barnwood to blacksmithing Tik Toks, perhaps something fundamentally anti-modern is afoot in the hearts of many young people.

It feels fair to claim in an almost axiomatic sense that aesthetic expressions have intense and often entirely subconscious consequences in the behavior and worldview of those who view or listen to them. A study of music clearly demonstrates this; In former times, it was well-known that musical ‘mode’ could incline the listener to a particular sort of behavior or disposition. Aristotle states:

“… melodies themselves do contain imitations of character. This is perfectly clear, for the harmoniai have quite distinct natures from one another, so that those who hear them are differently affected and do not respond in the same way to each. To some, such as the one called Mixolydian, they respond with more grief and anxiety, to others, such as the relaxed harmoniai, with more mellowness of mind, and to one another with a special degree of moderation and firmness, Dorian being apparently the only one of the harmoniai to have this effect, while Phrygian creates ecstatic excitement. These points have been well expressed by those who have thought deeply about this kind of education; for they cull the evidence for what they say from the facts themselves…”

It was mere months ago that Elon Musk tweeted the song “Let the Good Times Roll,” an upbeat rock song released in 1978 by Bostonian rock band The Cars. If one listens to the song keenly, and observes the shape of the passions which arise in hearing it, it becomes immediately clear that the song’s optimistic, vaguely juvenile and raucous sultriness is totally congruent with Musk’s tycoonish ambition. His endeavors as an investor are not divorced from an aesthetic culture; they are really one in the same. Moreover, even the band’s name — The Cars — grants his tweet a hamfisted adjacence to his status as the head honcho of the car company Tesla. In “letting the good times roll,” he is talking about furthering his ambitions as a magnate in a manner that hearkens to the “morning in America” days of the eighties. His cultural franchise is one of a necromancer, claiming the haughty dreams of American cowboy capitalists are still alive.

While Musk has a strong following among a certain sort of young man, the cult of personality around him is not total. Many admire him greatly — but perhaps just as many are skeptical of his rollicking antics and Promethean visions. I’d argue that inasmuch as one finds Musk to be an insignificant or untrustworthy character, one is also likely to be taken with a more classically reactionary mode of both aesthetics and culture. Among young Americans with a ‘conservative’ bent, there seem to be those who want to do adderall and have premarital sex in a Tesla — and those who’d much rather sit by candlelight, reading Chaucer in their jolly hamlet over pine needle tea.

This latter group is still in a drowsy state; the concept of natural, traditionalist romanticism has been brazenly wielded by generations of posturing buffoons — during the back to the land movement, romanticism was a flight of fancy used as a mere accessory in an era of orgiastic drug use, obscene art, and dimwitted egalitarianism. The great majority of those who indulged in it rapidly returned to civilization, abandoning their fallowing farms and homesteads to become executives at companies like Whole Foods and Apple. They were also overwhelmingly secular leftists, who seem to have an almost biologically nihilistic imperative. Today, where one finds a disingenuous interest in ruralism — one finds an absence of genuinely reactionary sentiment, and a latent progressivism, however milquetoast. While I cannot say it with certainty, I would conjecture that today’s young ‘reactionary romantics’ may prove to be bellwethers in a broad and lasting shift in American conservatism. Should this tendency be nourished and given room to grow, it’d be liable to pave the way for a genuinely anti-democratic, market-skeptical shift in right-wing American culture, and perhaps even toward the establishment of a new American ancien regime. Such a shift would present a natural counterpoint to the tired and faltering ‘Strip Club Republicanism’ (as I call it) of the old GOP; fusing earnest traditionalism with a revival of poetry, religious orthodoxy, and a romantic view of ecology, craft, and livelihood.

II. The Empire State: Sleeping Monarchy

One of the hallmark elements of political reaction is the simple admission that “I am what I am.” The modern progressive, for example, may state that ‘everyone is an artist’ and ‘everything is art’. The reactionary, by contrast and if he is not an actual artist, simply admits that he is not at all disposed to the creation of art worthy of the name; and carries on his life with not a modicum of grief about that simple fact. He is likewise unimpressed with so-called ‘modern art,’ being that his conception of beauty is governed by objective characteristics. In quite the same fashion, he is liable to make a similar admission in all realms of life from politics to religion to morality; his implicit point of view is the acknowledgement that hierarchy exists, and that it is always better for a system of cohesive moral authority to exist — even if dysfunctional — than to abolish it and risk a descent into chaos.

This can be contrasted with the essentially phony system by which authority is meted out among secular progressives: their admonishments to ‘trust the experts’ make one wary, for the mechanism by which those individuals become ‘experts’ is extremely nebulous and subject to grave wilings as compared to, say, a Monarchy. It is also readily identifiable, in an intuitive sort of way, that the allegedly liberatory character of the modern system of ‘experts’ acts as a sort of ‘moveable monarchy’ — the winds change, and the manner in which public trust is legislated is subject to constant regime change which operates in a dishonest fashion: American yeomen are quite sensitive to the shennanigans of those who say one thing and do another, as the NPR-adjacent set in this country so often seems to do. It should moreover be stated for the sake of simplicity: There is no ‘affirmative action’ in a Monarchy by divine right, and ‘culture war’ was often kept contained in the Courts of Nobles. Such was the nature of the political stability of the Middle Ages.

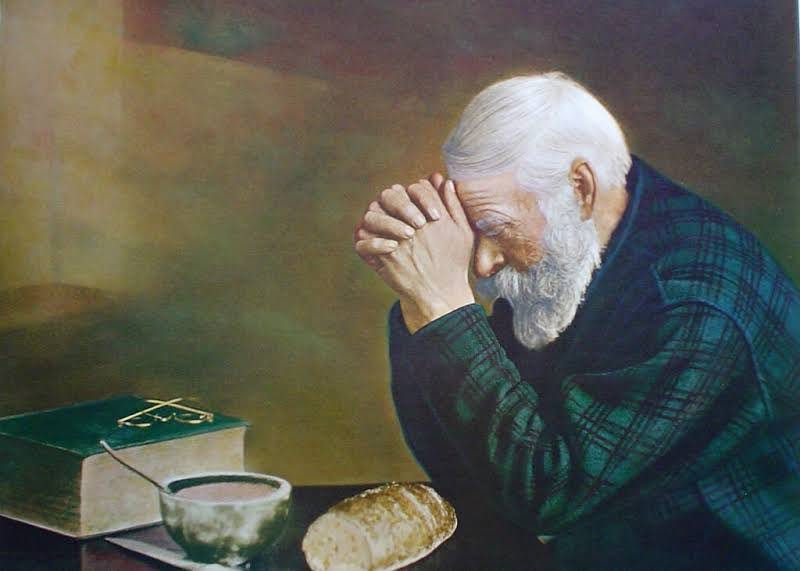

And in total contrast to modern mythologies regarding peasantry in the days of Monarchism, I suspect there is reason to believe the vast majority of those subject to Kings and Lords throughout the ages were not particularly disgruntled. A wise peasant understands his place; he continues his lot in life without complaint. His sphere of laboring and merrimaking is simple and small, and in his own domain he exercises the agency he has. In the days of Kings, there were not CCTV cameras, police cars, and agencies monitoring the Tweets of peasants. Nor was there much of a political ‘news cycle’. The great mass of peasants in Medieval Europe seldom interacted with lawful authorities; their understanding of the Monarchy under which they toiled was often dim, and its particular dramas were generally of no import to them whatsoever. The relative remoteness of centralized power during these eras was, by contrast to the heinous spectacle of modern democracy, a blessing to the simple Catholic peasant, for he felt no responsibility to the tides of power or their projects. And in such a state, he could simply toil, pray, and hold fast to his family, knowing his purpose.

So too with life in the State of New York. As a Catholic layman, I find this state to be among the most spiritually nourishing states one could possibly reside in for the simple fact that I am relieved of all the stresses and dramas of a citizen of a modern democracy. Here in ‘deep upstate’, I am essentially entirely un-represented at the State Capitol. My vote is of no importance whatsoever in any election but the most local; even then, relatively low participation rates in Town and county governments, combined with long-running mini-dynasties in those governments render my opinion essentially worthless. Furthermore, Albany is physically distant from my own smallholding; those who busy themselves with the management of the state seldom think of us, and when they attempt to, their efforts are so alien as to be laughable. The real result of this state of affairs resembles, in the actual day-to-day life of citizen-subjects, something quite like a Monarchical system. I pay my (quite high) taxes, I avoid the constable, I ‘render under Caesar’, and for this, I am essentially ignored and without any political stake in the future of the State. And subsequently, my blood pressure is lower, I do not follow the news, and I can focus on prayer and my vocation.

A bit over a year ago, when I was in New Orleans, Mardi Gras was reaching its apex. While the masses howled and cheered and caroused, I found myself in far more placid company — I visited a fraternal house owned by a society called Tradition, Family, and Property. There, I dined with the men, who all blessed our repast in bold, deep prayers in Latin; the dining room was gilded with antique portraits of famous French Catholic counter-revolutionaries, virtually all of them martyred. The discussions were of a seriously elevated caliber; though the swords on the wall might lead one to think these people were mere role-players or nerds, (and perhaps there was some of that) they were all exceptionally well-read, the sorts of men for whom Western civilization was worth a tireless defense — and thought and study in their classical sense a high virtue.

“There’s been a frenetic intemperance in our civilization,” said one of the men as one of his compatriots poured glasses of brandy. “Beginning with Martin Luther, an essentially revolutionary spirit has caused every ounce of darkness in the fallen heart of men to bubble to the surface — upending everything. Thus began the senseless ransacking of the West.” The brandy was refreshing, and another chimed in — “first, they attacked the Church; soon, denominations split into the hundreds, until eventually even faith in God was wavering. Then — communism, transhumanism, and an emptying out of Western grandeur and beauty.”

By God, all agreed, such forces were doomed to simply do themselves in; it was our task as traditional Catholic men today to weather the storm.

This term: ‘frenetic intemperance’ is exactly what I have stood against for some years now; I saw it in my heady days as an anarchist — the juvenile desperation that lay at the pit of the hearts of ‘revolutionaries’ and rabble-rousers. A certain darkness in the flesh and soul which drove them to topple things, to ‘de-construct’ old orders and to spit at the wisdom of the proverbs and adages of their grandmothers — and to drink and drug and screw. As I returned to my apartment, walking by the throngs of drunk and largely Godless people, I reflected on it and simply thought that democracy was scarcely different from the crowd I observed. And as I visited Saint Patrick’s in the morning to receive my ashes — without the slightest hangover — I felt intuitively drawn away from the delirious heaps of humanity who pile atop one another in search of the very order and peace they’ve come to reject. So began Lent.

This is what I mean when I say “I love New York.” Thank God for those monstrous concrete edifices at the center of old Albany — for accidentally shielding us here in the hinterland provinces from the storm of modernism and democracy. I only pray that you continue to ignore us; for here, the geographic center of an American reactionary revival may soon burst forth. And the quiet labor of scores of humble peasants may overturn the ugliness of the world they’ve constructed; by the grace of God, a return to order could well be afoot — and the ‘frenetic intemperance’ might come to its dying breath.