Newcomers

The Search for the 'Last Best Place'

In 1959, the great Catholic Bishop Fulton Sheen wrote a book titled Peace of Soul. In it, he addresses the causes of both World Wars from a psychological perspective, and outlines the core causes of modern man’s “frustration of soul.” Of the frustrated modern man, he says this:

“He changes his philosophy as he changes his clothes. On Monday, he lays down the tracks of materialism; on Tuesday, he reads a best-seller, pulls up the old tracks, and lays the new tracks of an idealist; on Wednesday, his new roadway is communistic; on Thursday, the new rails of Liberalism are laid; on Friday, he hears a broadcast and decides to travel on Freudian tracks; on Saturday, he takes a long drink to forget his railroading and, on Sunday, ponders why people are so foolish as to go to Church. Each day he has a new idol, each week a new mood. His authority is public opinion; when that shifts, his frustrated soul shifts with it.

“There is no fixed ideal, no great passion, but only a cold indifference to the rest of the world. Living in a continual state of self-reference, his conversational “I’s” come closer and closer, as he finds all neighbors increasingly boring if they insist on taking about themselves instead of about him.”

Of course I find his diagnosis utterly relatable, for the great majority of my adult life could fairly be characterized as a series of hotly impassioned phases in which I sought to snuff out the ghastly spectre of aimlessness. I sought to articulate some eternal reason for my life; something so impossibly true that it might deliver me from ennui, self-involvement, insensibility, and sloth. But as I sought that thing, the “center” moved as I walked. As I forayed into communism and anarchism, the grotesqueries of those ideologies crept up on me; as I wandered into environmental radicalism, the hard-heartedness of misanthropy bit me and turned me away. To be a hippie, a punk, a pacifist, a revolutionist, a materialist, a skeptic — each was the same in spite of differences in packaging: Each was a rational ideal hatched from a profound desperation of the soul that sent me groping through streets and library aisles alike — and ultimately through myself — for some kind of “center” that could hold forever.

It is this search for an essential, real, permanent “center” in the soul of man that has led to rivers of blood on streets in France, Cambodia, and Mexico; it is this search that seems to be the phantasm behind almost every harrowing and dark novelty in the modern era. Then again, it is not strictly modern; even Saint John Climacus wrote about it in A.D. 600. Man’s search for meaning is an utterly timeless feature of the human psyche.

But the nihilist in each of us is tempted to wonder whether every attempt at developing an external ideological framework onto the human psyche is not a pointless development; one wonders whether Max Stirner was correct in asserting that one’s own desire in the present moment might be the only ‘solid’ hard point that a human being could ever truly grasp for in the end. Going even further, the sullen Norwegian Peter Wessel Zapffe might’ve even been correct when he said:

“[Man] is in a state of relentless panic.

“Such a ‘feeling of cosmic panic’ is pivotal to every human mind. Indeed, the race appears destined to perish in so far as any effective preservation and continuation of life is ruled out when all of the individual’s attention and energy goes to endure, or relay, the catastrophic high tension within.

“The tragedy of a species becoming unfit for life by overevolving one ability is not confined to humankind. Thus it is thought, for instance, that certain deer in paleontological times succumbed as they acquired overly-heavy horns. The mutations must be considered blind; they work, are thrown forth, without any contact of interest with their environment.

“In depressive states, the mind may be seen in the image of such an antler, in all its fantastic splendour pinning its bearer to the ground.”

This “pinning to the ground” was the work of my early adulthood; it was the daily meeting-place in which all of my own ‘wandering’ took place. I read this and that, allowed myself to be swept into this or that fringe idea, almost daily — in an exhausting attempt at somehow exorcising the “feeling of cosmic panic” that Zapffe describes so tragically here.

But of course, my journey through “cosmic panic” was also a literal journey in the sense that I traveled from place to place. Far be it from me to endorse the ridiculous truism of “wherever you go, there you are” completely — though it contains its kernel of truth — I found that each place I visited was a sort of “skin” I could wear that would allow me to see differently. Each time I departed from one place in search of another, I felt myself sliding out from under the “pinning to the ground” that Zapffe described.

True, in arriving somewhere new, a man is every bit himself — but that self is refracted through the potency and shape of a new place; he finds himself, though his essence is the same, ‘poured into a new container,’ and as such, he feels some sense of relief or rejuvenation in arriving. Each change of place becomes an exercise in novelty strong enough to distract from the profound “frustration of soul” the good Bishop Fulton Sheen described.

I found a copy the Bishop’s Peace of Soul in a small 24-hour library on an island far from the mainland. I have no interest in naming this island for reasons that will become apparent throughout the course of this essay — but suffice it to say it is the sort of island where one seldom needs to make the daylong trip to the mainland, and it is situated in a vast sea, in northern country where spruce and sugar maple and endless winters are natural and routine. As I slouched upon the pristine shores of this obscure place, eyeing the distant horizon and the dimmest, furthest tendrils of the mainland’s green hills, I couldn’t help but wonder if the “frustration” the Bishop described might eventually completely despoil this jewel of an island. I wondered if I was only passing through the last wisps of a ‘purer’ place; a place that could not remain innocent for much longer.

For as places go, this island is a jewel by any reasonable standard of the word. It is clean and heavenly, untrammeled, heavily forested, and largely undeveloped. Its year-round residents could, in total, fit in a large banquet hall together — and in interacting with any of them, one finds themselves smiling at the ginger manner of speech each of them employs. Not a one of them is in a hurry, for this is not a place where it would even be possible to be in a hurry. Theirs is a world of slow boats and missed shipments, where the hour of the day is never of any import whatsoever — and where one is inevitably sucked townward to the tavern, again, for long and mirthful nights with one’s islander compatriots. There, a ragtag bunch of tourists might sit as well — variously perturbed and delighted that there seems to be nowhere on the island where they can purchase taffy, fudge, and tchotchkes bearing the island’s unassuming name.

And when the subject of house-keys came up in a recent conversation with a few of the residents, not a one of them could say with any certainty where their own keys might be — for they never use them. Cars are left unlocked and home doors are left wide open all day. Drugs are essentially unknown, and the yearly roster of crimes could be counted on a single hand of a man who’d lost a few digits in an accident. By some accounts, there are even entire years that pass where there is no crime at all. I ponder this as I stare out into the spotless forest, whose leaves rustle timidly in the breeze as the Milky Way somersaults through the yawning darkness above.

Virtually any thinking person would adore this island. True — it is not the sort of place where any who’ve a serious need for trips to Marshall’s and Panera and Starbucks would feel at home, but aside from the dubious pleasures of America’s “strip mall world,” this island provides all that a human being could reasonably need, and it offers it up in its most pure and tranquil form.

Of course — it has been “discovered.” New developments are springing up around the island; from-aways with Starlink and remote jobs are finding their way to this “last best place.” Local builders have multi-year waiting lists, and the bill for a new-construction home might run you $600 per square foot after a long wait. Already-existing homes are now unaffordable to long-time island locals, and old-timers report that there are now many residents who “don’t come down to play euchre with us” and fail to wave as they drive by other cars on the road — a mortal sin in rural island culture.

Again and again in my travels, I see the same story — enthusiastic locals of some obscure backwater share their love and pride of place with visitors, admonishing them to ‘move on in!’ But later, they find themselves eating their words — wondering whether they shouldn’t have been so friendly at the outset. For they realize they may have only succeeded in attracting newcomers who, as Bishop Sheen says, “find [their] neighbors increasingly boring” as the months wear on, and in time, the living organism of their home-place starts to go limp and pallid — and their own children are forced by a rise in real estate prices to move elsewhere. Later, condos rise on the once-small horizon; property tax hikes come in the mailbox like a bad omen. No one says “good morning” on the trails anymore, traffic starts to choke up village streets — and one might even start finding needles at their favorite fishing hole.

Sometimes, this even brings talk of war.

To what extent does this pattern issue from modern man’s “frustration of soul?” What are the newcomers to this country’s off-beat and pristine hinterlands aiming to find by moving? Why do some seem to let their new place of residence shape them — and others seem to want to shape their new place of residence into a copy of whatever home-place they left?

And, if it can be considered an inevitability that Americans — and particularly moneyed Americans — will seek out the “last best places,” how can they do so in a way that does not destroy the very thing they seek and celebrate as they forge out into purer, quieter, more jolly stretches of far-flung American hinterlands?

It is tempting to imagine that there is no suitable answer to these questions; that, to the credit of our cynics, the only defense a place might have against “rural gentrification” is to stay off-the-radar, secret, unmentioned and unnamed. But, conversely, it is not especially difficult to see that nowhere is an island — and that this is even true of actual, literal islands like the one I am now on.

In the era of Google and Zillow and Reddit and Instagram, whatever remnants of the old, virginal, ‘clean' and ‘free’ America will certainly be discovered.

It is with some sadness that I must report that basically every ‘last great place’ in this country I visit — and I go to great lengths to visit such places constantly — is already in the process of being “found.” All of the changes involved in that process seem to involve these places becoming less and less “like themselves,” and more and more reflective of the wider human monoculture one finds on more well-traveled routes. In time, ‘discovery’ seems to be coextensive with incorporation into the wider culture; accents are lost, building codes implemented, tax increases occur, and the crisis of unaffordable residential real estate forces the children of that place to move away. Corporate chains come in, foreign ideas, and the ‘organism’ of a once-pristine community begins to harden up into a weird simulacra of its original essence. This all begins with “discovery” — and discovery now seems to be an inevitability.

Therefore, insofar as I am able to tell — keeping a place a “secret” is only a fantasy in the end. While a far-flung place can practice the Fight Club rule for a while — “The first rule of Fight Club is you don’t talk about Fight Club” — it is only a temporary measure. Silence can only arrest the all-seeing digital eye for so long. If anything, the dynamism involved in rolling with the changes that inevitably flow from discovery is the likelier bet for keeping a community resilient in the twenty-first century — but even this sort of thinking cannot suffice by itself in the end.

Ultimately, the central conflict seems to be more akin to the one described by Bishop Sheen — and it is a national phenomenon more than a local one. For often, the great mass of internal migrants in the American nation could be described as suffering from the “frustration of soul” the Bishop describes; they are disillusioned and wandering, searching feverishly for an answer in a frightful landscape in which the goalposts move daily. Operating without any sense of ultimate truth or immutable principle, they are less moving “to” a new place and more moving through it. In many ways, “moving to Vermont,” or Montana, or Maine, or West Texas — is the spiritual cousin of going vegan, becoming addicted to Breitbart, joining the DSA, obsessing over QAnon, or getting into crystals and chakras. It is a swinging of the pendulum; an article of overcorrection in the wandering heart.

For, as I am fond of often saying, it seems to me that the hallmark of the Western intellect is overcorrection. One begins with a problem that is absolutely real and in no sense imagined and develops a view of how that problem came to be. They then do the precise opposite of whatever it is they think caused the problem — which then creates more problems. This second wave of problems is viewed the same as the first: One must swing radically in the opposite direction, causing still more problems. And so it is that a modern man might live his years wandering through phases of reactive rage against the various trials and inconsistencies he faces in his search for ever-elusive clarity, truth, and perfection.

This process can be as subtle or as dramatic as an individual’s personality allows. Some will wander in this manner in humble quietness; others will feverishly move between Hinduism and socialism and esoterica, aliens and shapeshifting Semitic overlords, moving on to the keto diet and obsessive workout regimes, and on into polyamory and drug use — finally coasting out into Margaritaville and Calvinism and flouride conspiracy, et cetera, et cetera. The process is endless, whether done with a dramatic flourish or conducted quietly and internally — and it is allowed to occur because modern man lives in a psycho-spiritual landscape that is devoid of any timeless, permanent virtue, principle, or theology. His mind is as mercury on a flat table, blown by the wind — shapeless and itinerant, forever.

But what “problem” lay at the center of the “from-away’s” mind as he moves from San Jose to rural Maine? What is the “original sin” in the cosmology of the native Bostonian that drives him out to Boulder or Bozeman?

For some it is a tax hike or a pile of shit on their doorstep. A needle on the curb at their toddler son’s favorite park. A riot that burns a city center to blazes. A mass shooting or a warrantless police invasion. Crowds and crowds of people and tourists, rent increases, tattooed immigrants on mopeds, anxiety diagnoses, bad memories of Covid, homeless hunched over and high on tranq, a hunger for the untouched night skies and the clarifying truth of the mountains — an acute knowledge that whatever we’re doing here just ain’t working, and a vague sense that things are still better elsewhere (for now, at least).

Of course, the problems we perceive — and I say perceive because some are more objectively real than others — are only frightening if we do not believe we have the agency to solve or address them. When governmental or market forces metastasize into faceless behemoths capable of radically reorganizing life, culture, town, and nation — and one gets the acute sense that their vote, or dollar, or petition is incapable of influencing the outcome of what they do even one iota — one thinks to run. And that is, to my mind, a forgivable impulse.

Yet very often, as one runs, one brings the very thing they were running from with them. Like a man running out of a burning building, his coat is on fire — and in running into his neighbor’s place, he is only spreading the fire to the building next door. Only by understanding the universal and absolute principle of how fire works could he save himself; only by an acceptance of the physics of flame could be walk into his neighbor’s door as a friend and not as a threat to his life, peace, and sanity.

It is a simple enough principle: If the “frustration of the soul” that leads to so much frenetic anomie is caused by a “continual state of self-reference” (as the Bishop claims) — then its antidote would be found in some kind of universal, immutable principle. A principle so fixed and clear that it confers meaning upon human life and activity as reliably and completely as the physical principles of combustion lead to flame — a timeless, clarifying absolutism that will go unchanged no matter what a human mind might wish to do with it. Metaphors of fire and combustion go a long way here.

For what is a Christian who is said to be “on fire for God” doing that a modern secular person is not? The Christian with “fire in his eyes” may not appear very differently from the partisan communist in his fervor — and yet his fire seems at least vaguely capable of producing a result that is not quite so ephemeral and fickle as that produced by his secular friend.

Consider the Monastery: It is a series of buildings, usually in some beautiful, isolated place, where devout men live lives of chastity and prayer for the sake of Christ. One could visit as a tourist, one could visit for a spiritual retreat; one could even visit as a postulant with some interest in one day accepting Holy Orders as a real live monk. The Monastery could be of tremendous historical and spiritual significance — it could even be among the first and longest-running Monasteries on earth, and any two visitors to it could arrive with strikingly different points of view.

But what separates the tourist from the monk? What separates the earnestly spiritual visitor from the one who arrives only for “the history” with Selfie-Stick in hand? It is the question of whether the spirit of what makes the Monastery a Monastery is to be lived or or only merely studied; it is a question of whether it is a site of profound metaphysical gravity — or if it is only a site of strange and ultimately non-metaphysical human phenomena.

For the Christian, the ideal of Saint Anthony of Egypt in his hermitage is not merely a historical fact — it is a living truth in which he can, as a Christian, participate. Indeed, even the fixed and unchangeable ideal of Christ on the Cross is not entirely remote from him as a religious person; even if he himself will never face Crucifixion, even if he will live a fairly safe, pedestrian life far from the holy caves in which penitents wept or still weep — the Cross and the Cave are both his own territory; places containing a spirit that can accompany him everywhere. Whether he brings this spirit to the cubicle or the Vatican; whether he brings it to his family’s nightly prayers or into prison or into happy hour at Applebee’s — all that has been accomplished and brought to fruition by great Monks and Nuns and Priests and even by Jesus Christ Himself is for him to carry and wear like armor as a Christian. And this great and ancient set of ‘metaphysical clothing’ is unchangeable and living. It is his spirit as a Christian, and it ultimately defines him.

And insofar as I can tell, all genuinely durable human culture possesses some analogue to this living, unchangeable spirit. When a man from Donegal says, “oh us Donegal boys, that’s just the way we are,” he thinks of his West Irish heroes, past and present; he thinks of his own father and grandfather. He thinks of his neighbor who might be “the most Donegal type of man that ever lived” for his eccentric way of living the local color to the fullest. There is an essence there that is alive; it is no museum-piece but a living, breathing part of him that could never change, for he’ll always be a ‘Donegal lad’ and his status as such will propel him to pass the same torch to his own children. He could think and think, he could move to Bolivia, talk to a hundred postmodernist shrinks, drop acid, join the Army — he’ll still be a man who hearkens from a place where men think, speak, live, and believe a certain way one finds only in old Donegal.

And such constructs — though they could be picked apart and niggled down to nothing by the potent corrosive of modern rationality — serve forever as culture and faith. They provide a living human being with a rudder; they corral his energies into a single direction that is at least a good bit clear and succinct. It is only when the man from Donegal — or from Delaware, or Damascus — is incorporated into the modern world of post-national deracination and atomization that this rudder of his will ever falter or fail. The secular, materialist, post-ethnic, post-national man is a wandering man who is caught in a ‘funhouse’ of warped mirrors and mazes; he stares at himself and he is all he sees — and he is nothing. A vapor, a phantasm, a rambling bit of the breeze, he sets his mind to doing ontological Sudoku forever, and his pained and wearying game ends only when he finds something hard to grasp onto — it ends only when he feels the fire that is, at bottom, his own spirit. Until then, he is as “pinned to the ground” as Zapffe’s giant-antlered and long-extinct deer.

From all this, I might propose that the problem of “rural gentrification,” (for lack of a better term) is fundamentally a problem of spirit above all.

After all, this is America — a nation that was built by people who did not stay at home. All were at one point newcomers, though it might be trite to say it; all brought their ideals and visions and spirit to a new place just as surely as the “work from home” Californians bring their own baggage to Wyoming and Tennessee. The free motion of our citizenry throughout our fifty states is a feature of this country that will not be going anywhere anytime soon — and as such, fluxes in population are inevitable the whole country over. There are moreover many places in this country that could use a good influx, at least in theory — places like my own home state, which has watched a massive portion of its residents flee for elsewhere for the last forty years.

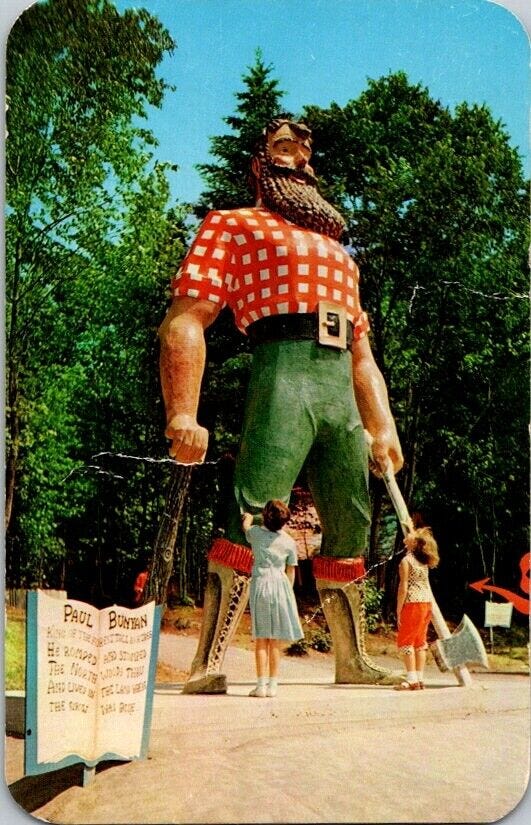

Of course, such an influx could only be welcome if our newcomers felt and understood the living spirit of our place. In an era of spectacle and simulacrum — an era of cartoons and caricatures and images that become fungible objects to be sold rather than reflections of life lived — this is a tall order. Spirit is so often lost in translation; many get the sense that understanding the spirit of a place is as easy as opening a book or reading an article. The Paul Bunyan statue over the water theme park; the lobster roll on Portland’s cobblestone streets; taxidermied bears in a Wyoming mountain tavern; Dolly Parton posters in a Carolina diner — all of these are only the topmost layer of icing on so many ancient cakes; they are copied images, condensed and easy to digest. They are glimmers of a ‘vacationized’ version of place that cannot communicate the entirety of spirit.

For the visitor, such images are harmless; they are all in good fun — they provide a cursory taste of a place and some insight into how that place’s people understand themselves in a dim, relaxed, incomplete sense. One knows this as they sit in the giant Adirondack chair by the gas station or munch Amish handpies in rural Ohio; they know it as they sip Tequila in an Arizonan bar-room or taste the fried green tomatoes of Alabama. It’s an interesting diversion, a change of pace — a photograph to put on the fridge when you go home that hurts no one.

But often those who choose to relocate adopt a mentality of ‘perma-vacation’ where these touristic images constitute the whole of their understanding of a place; they do not see the entire reality of where they have chosen to live — and often find it shocking when they encounter it.

I find myself thinking here of the Instagram account, Cheap Old Houses — and how some of the bizarre occurences this account has spurred could be made into a comedic reality TV show. When a wealthy liberal couple from Georgia found a house in my town on that Instagram account and bought it sight-unseen, they no doubt had a series of two-dimensional notions about how “quaint” Upstate New York is. Fall colors, white Christmasses, maple syrup, and snowshoeing trips in the hills filled their minds — and these images are, I’ll say as a local, quite true to form. But imagine their shock when, on move-in day, they saw their neighbors in their Tweedy Bird pajamas, smoking cigarettes on the porch beneath the “FUCK JOE BIDEN” flags; taking drags of cheap Reservation cigarettes in between hits from the oxygen tank.

Indeed, the Chamber of Commerce couldn’t have prepared them for that.

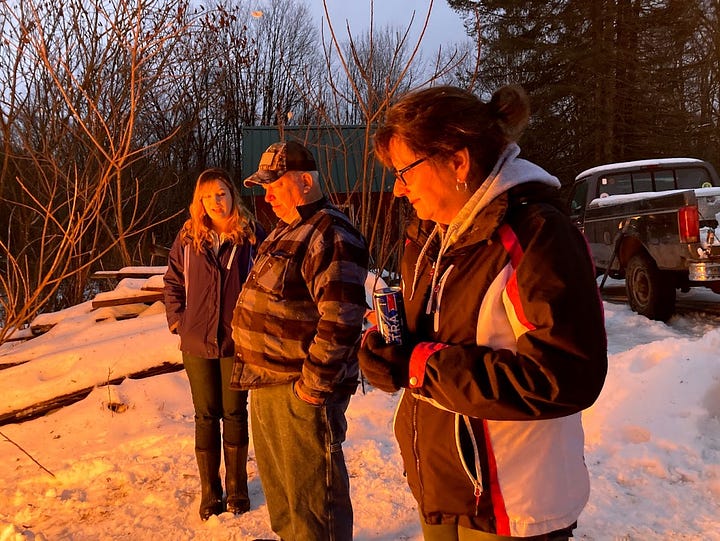

At day’s end, the spirit of a place is an extremely complicated thing to wrestle with — it is a thing that takes untold years to understand in full. An observant newcomer could, in emptying their minds of any illusions about a “perma-vacation” find lovely and edifying truths written into the the faces of the townfolk in their newly-chosen place of residence; truths that are often overlooked by visitors or even only vaguely understood by locals themselves. For a man to be of a place, he lives not merely in the present; nor does he live at all by philosophical mechanisms of his own creation — he lives instead in a world of mythos far older than him, inflected deeply with the shape of the land. The lilt of his accent mirrors some truth buried in the high hills of his homeland; his manner of problem-solving is not singular but a reflection of a life lived in the seasons of his acreage and township. His humor was bequeathed to him by the coyotes or the saguaros and thunderstorms; his practicality — or lack thereof — is informed by the vortex of elemental and cultural factors that reside unseen both in the land and the minds of its stewards.

Sometimes, this is anything but romantic; sometimes a man drinks too much or subsists on frozen burritos instead of venison. Sometimes he dumps oil in his yard instead of recycling it. Sometimes he’s a hothead or a racist or a holy roller who suspects you’re headed straight to hell. One could say the pricklier qualities of a “town man” might only be his own, and not at all of the place’s spirit — but they just as often are shared ‘prickles’ that every other man in town possesses as well. These weirder, more tough-to-stomach elements of local culture and spirit might be borne of the land and history of a place just as truly as its more palatable truth and mythos is.

Serious friction is often produced here; newcomers are often all-too-quick to start intervening and correcting long-time locals. They now and again become “active citizens” in a way that never endears them to their neighbors. There is no curse quite like that of a newcomer who immediately leaps up to shape his newfound town into a bastion of the city he left; a rural man most often wishes, in seeing the U-Haul arrive, that his new neighbor will not rush to change things. A newcomer could view his new town as a doll to play with — or as a daughter to marry, warts and all. The former yields the worst results, of course, and often results in newcomers departing in a huff in only a year or two. The latter is the path to mutual edification of both a town and its new arrivals — the idea of relocation as being akin to marriage.

In this marriage, there is a profound hope that is often overlooked by those who think and comment upon issues surrounding rural population change and migration trends. Far from the ossified, territorial, “keep this place a secret” mentality of many rural folks — which generally springs from an understandable cynicism on the subject of new people coming “from away” — there is a model of mutuality in internal migration that could both save towns from dying a slow death and bring those who come from elsewhere to know a profound “peace of soul.”

And like any marital bond, it must be approached without any tentative or conditional thinking; one’s “courtship” of a town must be conducted with an eye toward understanding regional personality and spirit. Just as the young suitor cannot behold a young lady and meditate upon all that he would change about her after marriage — so too with those from elsewhere as they weigh the possibility of taking up stead in a new place. Warts and all, they’d do well to see whether they could fit and be honest about what they find possible. If they are lucky, they’ll find themselves a spirit that breathes something undeniable and true into their hearts — a living force in which they can wholly participate and become an accepted citizen; a spirit that will nourish and edify them, heart and soul.

If such a shift as what I propose here — or something like it — isn’t possible, America’s rural hinterlands may well be at risk of becoming one giant country-club or seasonal tourist town. But in my view, such a thing is certainly possible. After all, basic wilderness ethics are now common to hikers, campers, skiers, and climbers; a majority of outdoorsmen now know that when we head into the woods, we had better take care not to leave a mess unless we’d like to see the magic disappear. In this regard, is culture any different from wilderness?

It does not seem to me to be a stretch to humbly suggest that as we each pass through America’s far-flung hinterlands, we move gingerly, leaving no ‘litter.’ That each forest has a certain ‘feel’ to it is well-known, and that it should be proctected and carefully stewarded is no wild idea but common sense. Culture ought not be viewed any differently; and just as the one who settles in the woods takes good care not to ruin it as he builds his homestead — he should do the same insofar as the people there are concerned, too. For at day’s end, the spirit of the land and the spirit of that land’s people “rhymes” and resonates, and taken together, they can provide one of the only known and proven salves for the “frustration of soul” that Bishop Fulton Sheen wrote about back in 1959.

As people continue to pack their moving-trucks and keep their eyes on cabins and cottages out in the boonies — I hope they’ll keep the spirit of the places they head to in mind. If they do, we just might get an all-around better America in the end.