We stepped off the North Country Express at an isolated, windswept crossroads in Clinton County, New York. Coming here is like slipping into the funeral Mass of a forgotten man; like eyeing the empty pews and the somber murmurs of a solitary Priest. Rust, decay, and obscurity conspire below the impenetrable overcast to exert a profound and dismal gravity on the soul that fills the heart with a weird and harrowing sort of awe. As the gales blew dust into our faces and the bus sped away on the empty road, we simply stood for a while in silence, thunderstruck by this ‘opaline haven,’ which has always felt to me to be an American analogue to Siberia.

American Siberia

“Bro this looks depressing as hell,” one poster said in a comment on a video I recently posted of downtown Massena, NY. In the video, I am driving my minivan through the desolate streets, eyeing dilapidated buildings beneath the eternal grey overcast as a brooding Quebecois acoustic song plays on the radio.

Far from the harsh sorrows of men, at the very top of the world, a murder of crows cackled and picked at the corpse of a roadkill porcupine. Beside them, a road sign pointed our way north, bearing the road’s strangely apt name: “Lost Nation Road.”

We loaded our bicycles with our belongings and began pedalling against the wind, forging upward through a gloomy plateaued landscape of fallow fields and taiga-like forests. Caved-in barns dotted the land; wires dangled from abandoned power poles. ATV’s rusted beneath rotting tarps — and the windmills spun overhead like geometrical cathedrals of a foreign religion. Along the roadsides, there were abandoned sneakers and shredded garments — detritus of a quiet and seldom-mentioned crisis on the northern border — and blinking thermal cameras monitored by the US Border Patrol. As we pedalled forward toward the bleeding northern edge of the United States of America, the cameras followed us, whirring in our direction on remote-controlled mechanical arms.

Then — a far-off horizon came into view from atop a giant hill. Smokestacks with blinking lights, highways, cities, sprawling farm fields and networks of irrigation channels all billowed in the distance like a mirage. Like pilots landing planes, we surveyed an immense valley below us, flying down the pavement at a speed that seemed impossible. My heart leapt into my throat; a wave of emotion swept over me. In more than a decade of traveling, I am not sure I have ever seen anything so beautiful, for the view is as endless as it is unexpected. One barrels northward through an apocalyptic landscape only to find a high and private heaven; a portrait of what the eagle sees in his solitary patrols. The land sprawls ever outward like an ecstatic vision, and the heart is roused into a gasping state of awe — I quite wish all men on earth could see it for themselves, for no camera can adequately capture it.

But the land on the horizon was not a part of my country — it was Quebec. For as we reached the end of the Lost Nation Road, where a lonesome cabin stands like a motionless sentry, the road turns abruptly. With all the finitude of an oceanic coastline, the 45th parallel halts any traveler here, and one comes to recognize that the impossible, sprawling beauty of the valley below is inaccessible here — for the international border is only a few yards away.

We turned east on the Frontier Road, where there were few houses and fewer cars. The wreckage of a housefire lay sleeping in the briars; and along the edges of the farm fields weird ‘portals’ showed the pathways of illegal immigrants bound for points north or south. With thousands of people furtively crossing every month, one realizes that this bleak, isolated hinterland is the first taste of America many of them get. For most, it will only be a bizarre and dreamlike memory and nothing more. For some, it may be a freezing, harrowing nightmare.

Finally, we arrived at our apartment — the upstairs of a small, sturdy old farmhouse directly on the international boundary. To stumble off the porch of this house would be to make an illegal international voyage. Our landlord’s cat was an international traveler as well: she was known to make midnight sojourns into Quebec.

We turned the lights on and settled into our warm nook along the frontier, staring out into the night to see the stars above the blinking lights of the windmills. The silence was profound; it was as if we’d slipped into an anechoic chamber, a hidden sanctuary, dwelling in the quiet, nourishing safety of the unknown ends of the earth. Though we were only yards from Canada — we were still in our homeland, warmly ensconced in our temporary northern home.

In Taylor Swift’s hit song Welcome to New York, she said:

Walkin' through a crowd, the village is aglow

Kaleidoscope of loud heartbeats under coats

Everybody here wanted somethin' more

Searchin' for a sound we hadn't heard before

And it saidWelcome to New York, it's been waitin' for you

Welcome to New York, welcome to New York

Yet when we bicycled into the nearest village the next day, the village was anything but aglow — and there were no crowds to be seen at all. With our apartment a full ten miles to the nearest grocery store, we’d take our bicycles west through the fog, snaking along the international boundary and down into the river valley in which the village of Chateaugay is quietly nestled. There, one sees only a rash of sleepy monuments to a long-gone era; countless boarded-up storefronts lie dormant along the main street, and tooth-chattering wind whistled through the vacant doorways of the buildings. Giant eighteen-wheeler trucks barreled through the town, hauling putrid loads of liquified manure and silage. As they rolled through, the windows on the old apartments rattled. A dilapidated house sported a “Fuck Joe Biden” flag and a No Trespassing sign.

Though we found ourselves in the same state as Times Square, Wall Street, and DUMBO, Chateaugay sits nearly six hours north of the city with whom New York State shares a name. They might as well be different worlds; for though “upstate” might mean Westchester to a Manhattanite, way up here, “upstate” means country radio, mounted deer-heads, shotgun shells, and a take-no-shit, self-reliant attitude. Upstaters are, by and large, an ornery bunch of embittered yeomen fed up with NYC-driven regulations and taxes; they are as rustic, living etchings of earlier Jacksonian men.

Though this is a blue state, its rural hinterlands are die-hard “Trump country.” Some even defiantly declare that Upstate should secede from the Big Apple — an idea that strikes as a fantasy when one looks seriously at the tax revenue sheets in the state budgets; but the fantasy persists.

Yet for all this, the Taylor Swift song about that faraway city played anyway in the Stewart’s gas station in Chateaugay — and the sleepy-eyed, neck-tattooed cashier joked about it: “I don’t think Taylor has been to Chateaugay.”

If she had, of course, the same lyrics might apply — for among the illegal immigrants, many of them are here precisely because they “wanted somethin’ more.” And without a doubt, there are some potent ‘heartbeats under their coats’ when they’re being chased through the woods by the Border Patrol.

I saw many of these migrants on my numerous bike rides from our apartment to Chateaugay that month. One morning before dawn, next to the little cabin at the end of the Lost Nation Road, I saw an SUV with tinted windows and Texas license plates. Beside it, a half-dozen migrants squatted in the grass, looking incredibly nervous. They were likely Venezuelans, as at least one was wearing a bandana with the Venezuelan flag on it. A few miles later, I saw multiple Border Patrol SUV’s speeding in their direction, engaged in yet another cat-and-mouse style skirmish with ‘irregular entrants’ to the United States.

Unlikely as it seems, the Canadian border has become a common route for many seeking to illegally immigrate to the United States, as Canada’s liberal tourist visa policies allow for an easy approach to an oft-overlooked portion of America’s borders. One needs only to fly to Montreal and get a taxi to Hemmingford or Huntingdon — or sometimes straight to roads that dead-end directly on the international boundary. Then, after a quick walk in the woods, they are able to call another taxi, or to get onto the North Country Express — the local tri-county rural transit bus. Once they can get to Plattsburgh or Potsdam, they are only a Greyhound Bus trip from New York City.

This route has become incredibly common. On one particular bike ride into the village, my wife and I were questioned by a friendly USBP Agent. He informed us that the Border Patrol’s Swanton Sector — a 300-mile zone from Ogdensburg, NY to Pittsburg, NH — has seen illegal traffic increase here by a factor of twenty in just a year. With over 20,000 migrants apprehended in the last twelve months, this sector is busier than at least two USBP sectors on the US-Mexico border, or so he said. Nonetheless, the crisis here is seldom covered in national news.

He also told us that many people die in their attempts to cross this border. Migrants from tropical countries often do not understand the risks of making a crossing during the winter months, and they are found in the springtime — victims of lethal frostbite. I wasn’t shocked. Having been raised in northern Upstate New York, subzero weather is routine, even with our warmer winters in recent years.

All this is to say that people are, in many cases, quite literally dying to become Americans. Meanwhile, in this part of America, many of the locals are — metaphorically — dying to get the hell out of here.

The irony is almost too absurd to process.

The US-Canada border has not always been this way. In fact, not so long ago, our fenceline with our northern neighbor was extremely porous, and crossing it was essentially only a formality. The villages bustled with trans-border trade of all types. Farmers veered over the line to mow their fields; villagers from either side would cross over for dinner parties and dances and to pack the taverns with mirth and jollity. They would often intermarry, share farm equipment, or let their cows wander into the other country without any problems or paperwork.

One man we met at the Stewart’s in Chateaugay was a native of the nearby town of Churubusco, where our apartment was. He told us that as kids, him and his friends would ride sleds down the icy roads, flying down the hill from America to Canada in what might be the most stylish and thrilling sort of international travel imaginable. Back then, there were no cameras, and no fines for irregular crossings — in fact, the Canadian border inspectors would let the kids warm up in their shanty and give them cups of hot cocoa.

“Those were the days,” he said with a wide grin.

We stood with the man for almost an hour at that gas station, listening to him chronicle the history of his beloved town. Churubusco was given its name after the Mexican-American war, where the US Military overtook Mexican forces in the Churbusco neighborhood of Mexico City in 1847. Many of those American soldiers were from a regiment of volunteers from Upstate New York, and when they came home, this far-flung patent of land on the frontier was named for their victory.

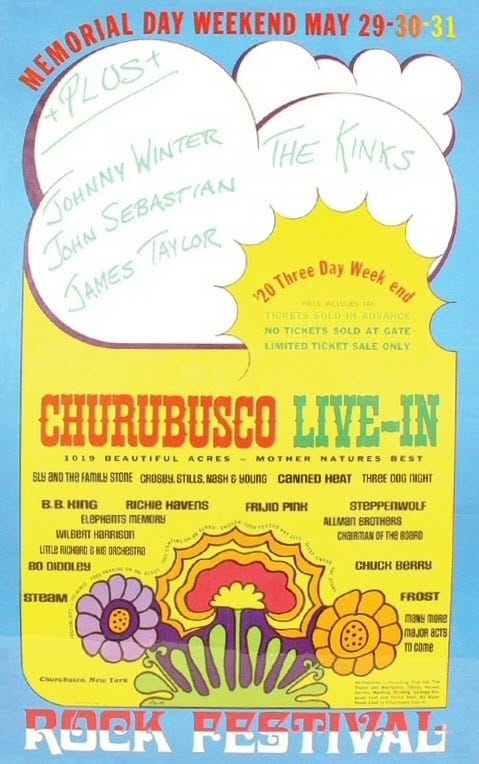

123 years later, another battle would take place — the battle between local farmers and hordes of hippies. Seven months after the roaring success of the Woodstock festival in Woodstock, NY, a handful of NYC-based concert promoters would begin an attempt to “take over” Churubusco to host the “Churubusco Live-in.” They printed flyers and tickets; they put money down on 1,000 acres — all they needed was for the locals to tolerate it.

“But we don’t really do ‘free love’ up here,” our friend said. “We’re not a hippie type of place. In fact, around Churubusco, it’s even considered a little risque to go around wearing something like flip-flops.”

The locals stridently opposed the Live-in — and went to war against the hippies. Lawyers got involved, the Town Board passed measures against mass gatherings, and the town’s lawyer, J. Bryon O’Connell even said: “That live-in will turn into a lynch-in. People up here aren’t used to long hair. They don’t fool around with legal niceties and they’re not going to put up with any nonsense from college students. If they come up Route 189, they’re just liable to get shot.”

The hippies did not, in the end, come up Route 189, and no “nonsense” took place in old Churubusco. The staunchly conservative farmers up in this northern backwater won, and their victory has shaped the culture of this place ever since.

There is no question that rural Upstate New York has been in a state of decline and decay for decades. For decades, the most popular intrastate move in America has been the move from New York State to Florida — and judging by how people talk around Chateaugay, that statistic isn’t about to change. Everywhere one goes in this part of the country, practically everyone knows someone who moved to the South — and if they aren’t considering moving there themselves, they know someone who is.

As our state’s residents flee for the tropics — our villages descend into decreptitude, and our small towns find their treasuries shrinking. The net result is that towns like Chateaugay raise the property taxes to finance services that are politically grandfathered in — which has the effect of punishing those who stay with higher taxes. Every time the taxes go up — more people move to Florida. It’s a death cycle that cannot be fixed but at the state level; but of course, our New York City overlords manage northern New York as a bitterly-hated colony. If they think of us at all, it is with scorn; if they enact any kind of change — it is never wanted or remotely helpful. And so decay ensues, and our citizens flee en masse.

Whether this decay is a tragedy or whether it is an accidentally protective shield against the more pernicious elements of what passes for “economic development” is a matter of personal taste — but in either case, I myself find the decreptitude of Upstate New York to be comforting.

Perhaps this is because if there’s anything I’ve noticed about places like these, it’s that they’re nothing if not honest. They don’t trick you with sweet nothings; they aren’t primped and plucked and groomed like some kind of a Barbie Doll beach resort. In fact, they’re a little forlorn and even ugly. The skies might be grey and the land might consist of a series of sprawling swamps and dying hamlets; the folks might be churlish and wild and prone to the whiskey. But they’re the real McCoy; they let their flag fly, warts and all, and if you’ve got the guts to love places like these, then in Upstate New York, you’re better off than a millionaire. And that’s how my beautiful wife and I were feeling as we pumped our bikes up over those tired old hills to ride to the village. Over our shoulders, Quebec sure did look pretty — but she was only the girl next door. Our real love was right here, we were in it, and it tasted sweet and filled us with gratitude.

After all, Chesterton said it best when he said: “Rome wasn’t loved because she was great. She was great because she was loved.” If we are indeed about to “Make America Great Again,” maybe that starts with a little love — even love for the dying, depressed places in this great nation.

Our last morning in that farmer’s apartment poured through the windows like a benediction; the end of our blissful north country month snuck up on us. The dome of overcast broke into honeyed rays of sunshine, and there was a dreamlike quality to trees, whose branches lilted madly in the wind as they lost their autumn leaves. Even in ‘American Siberia,’ where depressing weather is the norm, the land has its sublime and cheerful moments — and they are hard-earned.

Above me, an eagle performed wild maneuvers in the sky as we packed up our bicycles. He flew in circles directly over the US-Canada border — he’d fly fifteen seconds in Canada, fifteen seconds in the US, and kept repeating it again and again. Every time he came back into the USA, I felt something; I was glad he was back over here with me. When he finally circled back on the American side for good, I watched him bolt southward, and, as corny as it is to say it, I felt a sort of patriotism flood into me. Yes, the eagle belongs over here — he belongs over here as much as I do, and I am damn grateful we have that in common.

Soon, we followed the bird southward on our bikes, heading down to catch the bus at Dick’s Country Store — an isolated outpost where “1,000 guitars and 1,000 guns” are for sale. As we pedaled, a toddler stood on the porch of his beat-up old farmhouse, waving to us and shouting “I want to come to town with you! Take me with you!” His mother sucked on a cigarette and barked at her husband, who was already cracking a beer, and up ahead, wild dogs were threatening to shut down the road like bandits. We didn’t mind — we waved at the boy and smiled, laughing in the warm American wind, and the dogs took off into the bush.

After an hour or so at the store, the little old North Country Express bus chugged up the hill and let us in. We strode aboard with our folding bikes and rucksacks and sat down by some barefoot Amish girls and a couple old rednecks with one-too-many DUI’s, jostling east over the potholes — where the future is as unknown as tomorrow’s weather.

Neither of us was remotely excited to leave, and that feeling — that “I got no business leaving this place” feeling — told us everything we needed to know.

God bless New York, and thank you kindly for reading. You all are welcome at our house any time.

That little boy shouting to us was my favorite part of the trip!!! You know America is a good, where her children are friendly and trusting and welcoming!

Simply luminous writing! Thank you so much.