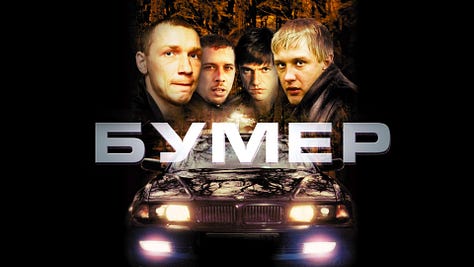

In Russian, the word "Бумер" is slang for a BMW sedan, preferably black. The 2003 film by the same name — pronounced "bumer" in English — depicts a post-Soviet, mafia-run Russia in which a gang of cynical, hopeless young derelicts endure tragedy after tragedy as they chase a vacuous mirage of success. The hallmark of the Russian gangster's idea of success was, in the late 90's, epitomized by the BMW. In the film, a shaman-esque woman in rural Siberia comes begrudgingly to the aid of this gang of young criminals when one of their men is stabbed with a screwdriver at a truckstop on the Trans-Siberian Highway. As she stitches the victim up, she begins ordering the others to peel potatoes for their dinner, admonishing them:

"Types like you, you go and die for nothing."

One of the men retorts — "It is not us who are bad, old woman, it is life that is bad."

She walks out of the shack, muttering to herself:

"Your car is scary, too — like a catafalque."

The 2003 Russian hit film Бумер might've been the only piece of media I consumed during my eleven-month "quarantine" aboard a US Military Training Center that felt real. The cynicism and almost suicidal desperation of the four young men who star in the film — Kostya, Ramma, Killa, and Dimon — somehow mirrored my own. I had joined the Coast Guard in a strange fit of desperation; after five years as an American hobo, glorious in my untamed freedom and hunger to wander across my country's most far-flung depths as I pleased, I fell for a woman who seemed to imply I'd need a real job if I was to keep her. In what felt like a perverse practical joke, I enlisted in the Coast Guard and mere months later, she left me and I was caught in the dismal world of covid-era military regulations and Soviet-esque practices — including indefinite solitary "quarantine".

Unable to see the light of day or to wander freely in the outdoors, I watched "Бумер" repeatedly, fancying for myself some kind of revenge against the soul-blackening fate of being kept in solitary confinement in what appeared to be a purposeless face-saving exercise by the high halls of governmental power. When I was briefly released to be transferred to another training center on the other side of the United States, I did not hesitate — I went straight to a car dealership and purchased a BMW 328i with cash. It was my first car. I'd previously shunned automobiles for over a decade, viewing them as a heinously wasteful expense and opting instead to hitchhike, bicycle, or walk everywhere even when I was living in quite rural areas. Now, the darkness of the covid-era military had bitten down on me sharply and wrested any ideological opposition to cars from my mind. As I watched my country descend into a darkly 'post-Soviet' sort of era during covid, I only wanted to feel the power of a German twin-turbo engine as a sort of balm for the intense nihilism of that chapter of my life. I wanted a catafalque.

Seven months later I'd be released from my second bout of lockdown and assigned to US Coast Guard Base New Orleans. Hurricane Ida had just slammed the coast of South Louisiana, and as I rolled into the city, the power was out. I was due to report to base the next morning, having been informed by my new Chief via text that we'd be engaged in some "irregular operations" due to the hurricane. My eyelids hung down like big black bags, my face was puffy and oily; I glided through the darkened streets of the city in my shimmering catafalque of a car, somehow already dead. Having arrived from California a few hours early, I drove aimlessly through the city's backwaters, where the streets were intermittently empty or, on odd blocks here and there, bustling with porch-sitting characters who'd waited out the storm. In the dark, the city might've been hard to navigate — but I'd been here before.

Five years before I was assigned to New Orleans as an enlistedman in the military, I did not arrive in a BMW. I hitchhiked from the California low desert with a gang of hash-smoking "Juggaloes" — fans of a band called Insane Clown Posse who paint their faces to look like demonic clowns. We'd been living with a settlement of squatters near the US-Mexico border, where veiny, lizardlike men crawled through fields of spent cluster bombs at a nearby Marine Corps bombing range, thieving for scrap aluminum amid live ordnance that would occasionally explode. They'd drag the metal fins into town on ATVs and in old, unregistered trucks, trading it to the local scrap dealer for their daily fix of meth.

Out there, we were at the intersection of ex-cons, illegal immigrants, anarchists, and hippies who'd tripped their way into third-world poverty. When someone robbed an East LA liquor store warehouse in a U-Haul, bringing back more than a ton of booze, the whole settlement ignited into a monthlong bender. Intermittent riots ensued at community events. Violence was spinning out of control in our encampment. When the crew of self-described "psychopathic clown gangsters" approached me one hungover morning about a free ride to New Orleans, I accepted without a thought.

We knocked across Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas in their rusted GMC Jimmy, which towed a too-heavy old camper trailer. The vehicle's suspension was supremely soft, cratering under its own weight as we changed lanes on Interstate 10 and swinging wildly on the curvy roads that wended along the international border to Rodeo, New Mexico. There were nine of us in all —

all packed into the Jimmy, with some spilling over into the flailing camper trailer. I stayed locked into the shotgun seat, navigating this motley crew through some of the most intensely scenic terrain in the American southwest. We became a sort of family rather quickly.

During a bad night in lockup at a US Border Patrol checkpoint in West Texas, that sense of family became almost rabid as we clung to one another in the detention center. The officers swore at us in Spanish, corraling us into the cell, never reading us any rights or even telling us we were under arrest. At the checkpoint, the dogs had smelled the Juggaloes' hashish — which I had exhorted them not to bring — and the fun began. By Texas law, if no one took the rap we would all be charged equally. A Texas State Trooper came in, making a caricature of himself: "Did y'all see the sign on the way into my state? It says Don't Mess With Texas..." My own fate was solely in the hands of one hash-smoking fan of Insane Clown Posse.

But as the lyrics of one ICP anthem state — "I'll always have my Juggalo family". And so without so much as a second thought he admitted guilt and the rest of us were freed. We putzed around Van Horn, Texas for a night as the Juggalo in lockup faced his charges. His wife borrowed my cellphone, calling her boyfriend in Vegas to bail out her husband, which he did. Turns out this gang of desert drifters had real family values, whatever one could make of their demonic clown makeup and polyamorous love affairs.

We arrived in New Orleans deeply exhausted. It'd already been one hell of a month. But in America, opportunity has many faces — including unattended plastic cups of Bud Light on trashcans. Bourbon Street is, for many of this country's most red-nosed lushes and drunkards, a paradise of booze. The ATMs reach into the pockets of tourists and 'spring-breakers' — $15 fees, known in the industry as the "blackout tax" — and the bars teem with puking, gurgling, scantily clad forms of flesh, all sweating pure liquor in the deep Louisiana humidity. Shoulder to shoulder, tens of thousands of American drinkers crush against one another in a deafening spectacle — the entire scene on Bourbon Street is, at its purest, an avatar for the grimmest elements of human nature. When the action peaks, the crowd is so loud and so blindingly ineibriated that doormen in gaudy suits simply blow a whistle loudly, without rhythm, chirping into the depths of the flock of neon-lit half-conscious drunks, pointing at the door of the establishment he wishes to corral them into like a referee on the game-field. There, they'll pay a dozen dollars for watered-down, ultra-sweet boozy nectars in giant plastic cups which have a zombifying effect. The entire scene is a churlish, medieval, mind-numbing display that overwhelms the senses of any sober-minded individual who has the misfortune of passing through.

As in the crowds of vomitously wasted peasants of jolly old medieval Europe, the crowd on Bourbon street has its share of opportunists and rogues. Raven-like, they eye the happenings of the street with a flavor of extreme lucidity that seems incongruous; these transients and urchins are just as drunk as the tourists, if not moreso, and yet their eye is eternally sharpened to the positioning of various leftover boxes on trashcans and half-full plastic cups on door ledges. Every alcoholic beverage left unattended is fair game; every white styrofoam box of half-eaten crawfish and gumbo is a few breaths of social engineering or just plain old gumption from the stomachs of the vagabonds for whom Bourbon Street is their carnival-like winter palace. The latter-day American hobo — known to some as a "crust punk" or simply a "crusty" — is a masterful entrepreneur who watches the detritus and off-scourings of mainstream New Orleans tourism and consumes them then and there in the streets until he is sated, unconscious and deafened.

"Are you emotionally attached to your leftovers?" one of them may ask you as you pass by with post-dinner restaurant box in hand. These inquiries are always startling to the tourists who are targeted — there they are, having just loaded up on local culinary delights for their first night of vacation in New Orleans, ready to hit the bars, and a filthy dreadlocked man in rags with tattoos on his forehead that say things like "WHITE TRASH" and "FUCK YOU" makes his mild-mannered and witty request for your boxed up leftovers. A tourist may stand there timidly in her leggings and Ugg boots, clinging to her boyfriend who stands stiff in his Alabama State jersey as they both wordlessly pass their unfinished dirty rice and po' boys to the filthy vagrant. As they walk away, the man mutters a cheerful word to himself, thanklessly tearing into the sustenance he's received from the gods of the street.

Such meals are often heavenly to the cast of street rogues — especially the recent arrivals. When we pulled into New Orleans, heaving ourselves out of the fetid humidity of the SUV, we were still hardened from months in the low desert. We were prepared for battle, and yet — at least initially — no battle did we find. Instead, as I turned down Decatur Street, I found a white box on a trashcan. As I opened it, steam rose out — it was an almost totally untouched filet mignon, complete with fresh broccoli and orzo in a cream sauce, still piping hot. I couldn't believe my eyes — after months of living on a diet of hot dogs and stolen liquor, a meal of this caliber constituted an almost unthinkable delicacy. I turned another corner, looking for a spot to wolf it down — and an untouched plastic cup of ice-cold beer was resting on a mailbox. I hadn't been here an hour and I was already scoring big. Down the street, a brass band was playing. I took my meal with intense relish and relief — I'd arrived in some kind of Garden of Eden for anarchist drifters.

But New Orleans is to the penniless vagabond what the carnivorous plant is to the rambling insect. With wafting, glorious smells, the whole scene greets the eye with a plucky sea of dreamlike colors; the city draws you in, lowers your guard, makes you pliant in its hands. Piece by piece, the Big Easy reconfigures you, lowering you to its below-sea-level spiritual state, miring you in a bayou of toxic buzzes and teeming, jolly crowds who in spite of their smiling cheer have descended to a moral nadir even Dante couldn't have dreamed. The cornucopia of street sustenance pours out onto the class of rogue vagrants like abundance falls onto aristocrats, and in time, the gnawing begins. Fights over panhandling spots, altercations with buskers, forays into heroin and risky sex ensue. You slowly realize that those who've been living on the street in the French Quarter for much longer than you are darkened, deadened, wandering in a lush and cackling hellscape that you are helpless to navigate. Droll nights of dining on the waste and drinking free booze transform into nightly debauchery that by morning escapes memory — save for the lost sleeping bags, puke-caked boots, and bruises and cuts. Like some kind of bizarre theatre of warfare, your compatriots disappear randomly — they may have skipped town, been arrested, transported to a detox center, or they may have absconded into one of the many squat-houses where needles are passed around and young men die by the scores.

After a couple weeks of sleeping in a park by the levy, I was offered a house to squat. A Filippino banjo-player wrote on a styrofoam leftover box the directions — he was going through the delirium tremens of alcohol withdrawal in a doomed attempt at drying out, and as such his handwriting was almost illegible. I and a few of my crusty friends wandered the streets of the Eighth Ward with this piece of styrofoam, stumbling from block to block in what looked like a rough neighborhood. We got lost several times, but we finally found it — a wrecked old house, half-caved-in, the ruins of an old New Orleans estate that had been ravaged by Hurricane Katrina.

It was dark as we approached; a big live oak had caved in the porch and we crawled under it. Most of the floors were totally rotted, but there was a barely discernible trail of plywood over the beams. We hesitated, but finally I led the charge across the path, nimbly avoiding the gaping holes in the floor. We arrived at a kitchen that was clearly still dry, complete with an intact countertop with a classy tile backsplash. There were a few blankets. Someone had etched the words "kill yourself" into the ceiling, and there were dozens of beercans and needles in the sink.

Even for this rugged band who'd been living in mud-huts in the desert a month before, these accomodations comprised some of the roughest we'd had in all our collective years of sleeping rough. But resilience is the word among tramps and hoboes, and we settled right in, hanging hammocks on the still-solid beams of the kitchen and back porch and stealing candles from the local dollar store. We cleaned up the beercans, buried the needles in the yard, and day by day, started loading books and scraps of fabric and old furniture into our one-room household. I ordered a typewriter on Ebay for twenty-eight dollars, shipping it to the squat — when it came, I took it nightly to Frenchmen Street to write poetry for cash alongside the other poets. I tapped out an abusrdly diverse array of written pieces for spare change, ranging from pet eulogies to sordid love letters. Haggard cougars would approach me about love letters to their boy-crushes — drunken football lotharios would overpay me to write their apologies to Mississippi prom queens. The money kept coming, and in time, I had saved up nearly two-hundred dollars — a fitting sum for an aristocrat.

Meanwhile, the rest of the bunch from the squat would begin "Bourbon surfing" — cutting off the tops of five-gallon buckets pilfered from the alleyways behind the restaurants and bringing them on skateboards to the corner of Bourbon and Dumaine. There, they'd beg passers-by by the thousands to pour a bit of whatever they were drinking into the bucket. A little Coors Light, a little rum and coke, a little slushy Margarita, all mixed into a devilish concoction in a massive bucket from which the crew of street pirates would dip plastic cups found on the street for a swill. The slurry would eventually become a harrowing shade of grey; a soma-like milk for penniless punk-rock boozehounds. Sometimes, one of the guys would strap the buckets to a tricycle they'd built from parts they found in yards in the Lower Ninth Ward, visiting me and the other poets for a tipple on Frenchmen Street to keep me sufficiently sauced for a few more hours of writing. Often enough, the tricycle wouldn't stop until reaching the end of the Bywater, where the abandoned Naval Base was — and a gaggle of drunk itinerant punks would follow like a ghastly procession to the pit of darkness.

The Naval Base may have, in retrospect, been among the darkest places I'd ever seen in America — and I had seemed up to that point to have made a career as a visitor of the worst examples of the American underbelly I could find. If New Orleans itself is really a carnivorous flower that preys upon the dark cynicism of the seekers and misfits who find themselves on freight trains and Lost Highways that wend their way to the city below sea level, and the wanton profusion of free food and booze on Bourbon is its alluring scent — then the Naval Base is its crematory and fangs; the place where the trapped soul is led to the dungeon in which his flesh will begin to die. There, like a stock exchange of souls, the grim architecture of the base — which was ruined by Hurricane Katrina — hosts a legion of ghostlike forms who drive needles into their arms, laying syphilitic and dumb, offering their souls whole for a brief gasp of something real. The revelry of New Orleans sucked them in; the headstrong nights where, piratelike, they sauntered the streets as kings — these castaways of modern America, runaways and head cases and abused kids, the few lumpens who were tough enough to travel the long road to the Big Easy. But what they sought was a neverland with no pain; they hounded out the freeing moments of the vagabond's life, suckling at the tit of a false heaven until at the Naval Base where they imbibed and fucked and shot up, they captured a glimpse of hell and either expired or sprinted far away, rattled.

Walking the trash-strewn promenade behind the base, along the canal separating the upper and lower Ninth Wards of the city, gangs of face-tattooed kids prowled the early hours of morning, and it was there that I walked alone with my typewriter in a mild bayou winter dawn. I was still drunk from the night before, haunted by a spate of recent overdoses, deaths, and arrests. Aimlessly, I detoured down along the river, seeing what I thought was a quirky art display. As I came nearer, it looked more like a makeshift grave. The epitaph read "OUR BABY" The grave was surrounded by little toys and milk-bottles — I had stumbled upon the grave of an infant. Weeping uncontrollably, I understood the city's dark reputation among travelers in full now. In just a few months, I had watched multiple friends overdose, witnessed death first-hand, and drank myself into oblivion in a manner that was anything but fun. Now, the apocalyptic reality of an infant buried in a makeshift grave amid the trash behind the ghastly Naval Base bludgeoned me brutally — I wanted to disappear to read Hobbes' Leviathan, alone in the forest, far away from the hideous world where life is "nasty, brutish, and short" and "a war of all against all."

I fled the city without a word to any of my compatriots; I hitchhiked north in a fugue, dead to the world. As I made my way up through the Deep South and toward Pennsylvania, I watched my body move from ten-thousand feet above, stone cold sober, shivering in the solitude one attains only when they've visited the gravest extremes of humanity — when they've sojourned into realms that few know. I sat alone at a bar in Tobyhanna, where dark-eyed cops glumly nursed their Yuenglings, and began to wonder if I had more in common with them than I had ever known. The chain of events that would follow this brush with demons — real ones — would lead me into the woods, where I'd build a cabin for a sullen and distant woman, and eventually, out of desperation, join the US Military.

My return to New Orleans in the BMW completed the circle. I had taken a multi-year, involuntary course in the human condition, circling all the way back to my breaking point in my shimmering German catafalque of a car, surveying the storm damage and finding that my old squat had been long since demolished. The Naval Base, however, was still chortling with the same great mass of lost souls that it ever was. Each day on my way to work, I drove by it, feeling chills on my shaved scalp under my military cap. I was not any happier for my removal from that bizarre winter carnival; I did not feel the least bit edified by the strange turn of events that brought me back to that devilish city.

On the winter of my return to New Orleans, I'd find myself at the Latin Mass at Saint Patrick's on Camp Street, alongside some of the same cops who'd brought my old friends to the coroner, listening to the Priest give his homily about demons and knowing what we all knew — that they are real. After Mass, I wept by the statue of Our Lady there beneath the arched ceilings of the Parish; I clutched my Rosary, newly reverted, praying for sanity on Bourbon Street and in the squat-houses, praying for the Light of hope and divine mercy to cleanse that old Naval Base. There — downstream of everything on the peevish, nasty waters of the Mississippi River — I felt a call to renounce the darkness, sneaking away to the sanctuary, beyond liquor, beyond BMW's, beyond the military; somehow even beyond death.

I returned home, eyeing the humbling force of another Louisiana rainstorm, lingering upon this world beyond death and demons that I had only just bathed in fully for the first time. I reflected upon the infant’s grave, the overdoses of the addicts, the suicides — violent and slow alike — and considered hope. I considered my own condition, which had driven me to this place; I stared directly at my fallible nature, which had governed me for so many years, sending me on dismal, wayward paths — paths which now seemed all to angle toward the agonizing ecstasy of pointless death.

And it was then, alone, by the din of the porchlight that I admitted aloud:

“I can’t do this alone anymore.”

Bravo! I loved every paragraph and can’t wait for more!

The thing about this is that it sounds extreme and far fetched but you look at the street kids in any number of US cities and you know it’s a common story that’s been repeated probably hundreds of thousands of times.