“When John Brown died in 1803, his development in the “New York Wilderness” fell into disrepair, but several years later his second son-in-law, Charles Frederick Herreshoff, moved to the tract and built Herreshoff Manor […] He offered strong incentives to get settlers to farm the land, but the farms failed. The mountainous terrain was unproductive and the growing season too short. When the farms failed, Herreshoff turned to raising sheep. When the sheep business failed, he turned to iron ore mining. When the mines proved to be unproductive he gave up. Herreshoff committed suicide in 1819 and soon the land began to fall back to nature.”

The name “Adirondack” is an Anglicization of the Haudenosaunee term ha-de-ron-dah, meaning “eaters of bark”. This was the grim witticism horticulturalist Iroquois in the fertile Mohawk Valley used to describe those Oneida, Mohawk, and Algonquin intrepid enough — or perhaps stupid enough — to decide to overwinter in the vast wilderness in the interior of present-day northern New York State. These ragged and starving hunters would take the near-suicidal trip southward to Oneida and Mohawk longhouses, through unbelievable snowfalls, in hopes of securing a lifesaving meal. Well before European settlement in North America was underway, the Adirondacks were not known for life-giving softness to human life, nor were they settled year-round.

Perhaps it’d be fair to characterize the newly-settled North America of yore to be not just one singular frontier; the reality was a bit more complex. Less like a vast sandbox containing equally-challenging terrain and more like a Matryoshka doll of frontiers-within-frontiers. Some lands stretched before new settlers first as briar and wood, soon fruited with grain, and in only a generation yielded supple and plentiful agrarian bounty. At the edges of these newfound ‘heartlands’, foreboding wilderness still leered. Much of it remains virgin and has never diminished, or if it has ever been tamed — was only tamed temporarily. And even within vast wildernesses that have forever defied the plow, there are still wilder parcels in which even hunters and loggers seldom venture. I suppose the romantic in me likes to think there are still places in our mountains and swamps that have only been seen by a handful of hearty men — and it may very well be true.

The Adirondacks strike me as one such ‘permanent frontier’. Their terrain is unbelievably gnarled and surly; striated plains of sand and dark water, tangled hemlock roots and metamorphic stone offer the farmer nothing — most were not foolish enough to even attempt the task of putting them to row and seed. Seams of iron existed but most proved fickle; even when rich, the logistics of removal to market were outrageously expensive and dangerous. The weather is tenacious and unstable — even violent. If any pattern in weather is discernible it trends toward gloomy overcast and frigid year-round cold. An avowed Adirondacker gets whiplash from the sky; wild swings in temperature and precipitation give him nothing to set the clock to. And in some silent hollows and seldom-tread mountains the sun does not endeavor to visit for weeks at a time. Any who know this strange region well will understand that my terms of description here are not overdramatized.

Far be it from me to consider myself a historian of the Adirondacks, I did nonetheless have the pleasure of reading a 600-page tome on the history of Hamilton County some years ago. Hamilton is one of two counties whose boundaries lay entirely within the Adirondack Park. This county, whose present-day population density is on par with that of West Texas, has a grisly history of failure and heartbreak. For decades, farming was attempted there, sometimes by sheer determination and often enough by duplicity on the part of land salesmen in places as far away as Manhattan and Europe. As I read the county’s chronicle, I only realized some three-hundred pages in that vitually every account of a farm started in the county ended in catastrophic failure, abandonment, and occasionally suicide. Charles Frederick Herreschoff was one such unfortunate, whose gravestone marked what may have been his most lasting contribution to the hardscrabble woods where he sought a civilized living. And today, Hamilton County has exactly one farmer, whose productive income is dubious.

Enter controversy. In today’s era, discussion about race is all the rage. All over the streets of cities like Brooklyn and Atlanta, murals depict the heroes of the black community. Along the US-Mexico border, rap songs about la Raza blare from low-rider cars, depicting Hispanics in Aztlan as latter-day Aztec warriors. Celebrations of culture abound, and many are warranted. Only a racist could deny the brilliance of Dizzy Gillespie or the bravery of Cesar Chavez. And yet one particular group sits at the sidelines of the party, quietly reflecting on the sins of their forefathers: It is those whose bloodline hearkens to Northern Europe.

For the North-American Anglo-Celt, the frontier is completely natural, however far removed from it he may be in the contemporary age. The continuous struggle to survive in wild landscapes and unkind turf has christened him and his progeny with a particular flavor of ingenuity, bravery, and yes — cruelty. His exploits on the Great Lakes built the largest business empires of his day; the outpouring of wealth brought south from the wild forests and north from massive plantations galvanized the bones of a feverishly expansive empire. Indeed, the computer on which I now type remains his bewildering legacy — even his frontier-ish ways brought this strange device to be. During the weird kickoff of the digital era the internet was described explicitly in terms of a vast terra incognita, akin to space or the wild West. Perhaps the very technological prowess he brought to bear on the world would be his ironical downfall. For though Northern Europeans are no more innately evil than any other people, their kin would weave evils of a more intense grandiosity than those of any other race. Their wills became amplified by unbelievable technology; and what might have been average crimes commit by any other people would become incredible spectacles of blood and exploitation. This occurred in no more than a handful of generations, backed both by the fortune of timber and topsoil he found in North America, by enslavement and conquest — and by the intense sacrifice and struggle of his pioneer forerunners. Every glory and every cruelty a stitch in our bones; this story is immutable and shan’t be made to shrink back by mere tittering.

For it is always rather easy to look hindwards and raise an objection. Should our great-great-great grandfathers have stopped their westward procession? Should they have retreated back to Europe, however violently unwelcoming it may have been? Should they have sat among the Indians, recognized their humanity, and laid their arms to rest?

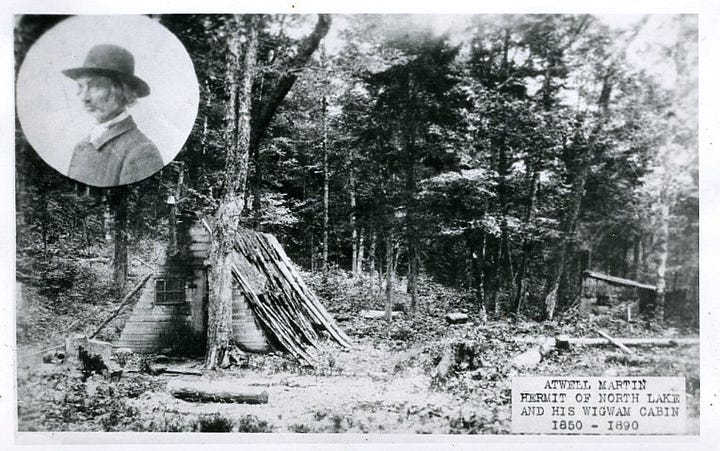

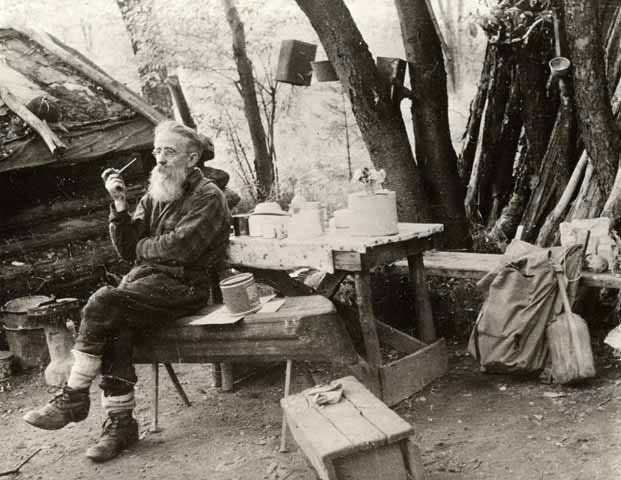

On this latter point, well, many did. So-called ‘white Indians’ and woodsmen often mixed — and especially in forlorn wildernesses like the Adirondacks. There, true equality seemed to exist, for the land was unconquerable by red and white man alike. Man’s smallness in such an environment is universal, and whatever disdain he may harbor for his neighbor might readily vacate his person in serious circumstances. Men like Indian Joe and French Louie — infamous trappers of the area — shared encampments often enough, and while they may not have shared traplines or a common tongue, they understood survival in a manner that afforded them a markedly more peaceful coexistence than in other arenas of the American frontier. One sees this rather plainly in the genteel dispositions toward natives of the French settlers of the Canadian northwoods, over and against the callousness of those who settled the Great Plains. The harshness of the landscape bore a strange fruit — a heightened tolerance, however small and oddly-shaped.

Sins were committed which one could not deny, but a particular beauty exists in these untrammeled lands and their storied inhabitants the likes of which is impossible to scoff at. So much so that in me — a native of the foothills which sharpen at the edges of Adirondack splendor — a dreamily romantic flavor of “Adirondack Nationalism” has always been present. Perhaps as I have traveled through the United States, this sentiment of mine has even widened to include a celebration of all of the harshest places, the unconquerable reaches of wild North America — the realms where civilization’s projects fade into obscurity and evaporate in sleepy-eyed guffaws and desperate chuckles.

For as harsh as the land may have been — and still is — an almost inexplicable hilarity is written into the land and her people. To sit in some unfathomable reach of a river whose name only a few hundred living men may know is to laugh the deep contentment of one who has momentarily evaded the violating clutches of man’s vast Leviathan. The breathless pursuit of more is utterly futile here. Even enough is tough — so tough you’ve just got the laugh at the fact that you could starve if you screw it up. Death is everywhere, sublimated into the drunken beauty of violent rivers, hoary frosted spruces, and vultures who drag muskrats to a sandy death. Roadkill abounds along vlys and swamped reaches of lake. Men carve up the guts of brook trout on aluminum boat decks, and power outages occur when an ice storm comes. Spend enough time in these woods and one finds that each of the handy-dandy tools afforded us by our global supply chain will fail at some time or other — and then you’re alone, dancing in monkish hilarity alongside death.

It would be fair to say, I reckon, that enough time spent in regions such as these render a man more himself than he is under fluorescent light and in city traffic. To make this remark is really a cliche, and yet it begs a wider inspection of the force which generates human culture. Continuous struggle, bitter poverty, maddening trevails which may drive a man to insanity, wild frightful windstorms, the burial of those who went too soon and bloody deerfly bites — these are the litany of sufferings, small and large, which drive a man to overcome himself and arrive even momentarily into the safe harbor of beauty. There, he inspects the sublime, he ponders God and His creation, contemplates woman and child and the cycles of life in all things. His life’s balance is tuned and refined; every stroke of suffering begets a more memorable stroke of romance. And as so many of these romances are weaved together into a life, they transmute onto future frontiers and their lineages to create a people. Such a grand thing, whatever cruelties and bitter days it may include, ought to merit as much an effort at preservation as any forest ever did.

Perhaps the ills of our day stem from a technological leap above real suffering and insecurity; perhaps after all, one does best to make no Promethean hurls ever upward to pure comfort and effortless existence. One finds that where these unfortunate luxuries visit the human creature, he loses romance and God, he forgets the wilderness so thoroughly that even when he is there he fails to see it. Love becomes as dry as a lawyer’s clauses, and the heart grows tired. Perhaps worst of all, he forgets his kin and their stories: he loses himself. And yet the American is ever the frontiersman; he will turn inwards unless he finds himself an unconquerable land, he will devour himself unto eternity when caged. The way I see it, this seems to describe the emergence of American leftism, post-structuralism, feminism, and the fanatical obsession with the twin Ouroboros of race and gender. The American woodsman’s great-great grandson, deprived of real suffering and wild trek, turns himself and the natural life of the world into an unsolvable problem that drives him utterly mad. To him I say: “Free yourself, my friend — away to the woods, and stay as long as it takes to remember.” Try as he may to forge into a frontier beyond his manhood, beyond his nation, beyond the sins of his ancestral past — he fundamentally remains a pioneer, and shall be imprisoned until he takes ownership of this incredible force.

It is for these sorts of cases that I think again and again on the dear old Adirondacks. These stolid and ancient mountains offer the dimmest prospects to the human man — they are as a perpetual frontier which cannot be brought to submit to his hand. True enough, today the Adirondacks are dotted with hamlets containing all the necessaries of the luxuried, from stores packed with snacks and treats to electrical lines and paved roads which serve all the little towns and trailheads. And even plenty of dead-eyed bureaucrats. It all rests on a far thinner crust than most probably imagine; its status as a tourist region makes it icing on the economist’s cake. One deep recession severs the ties, dries up the little credit unions, drives families to leave — again, as they have for all time. Barkeaters once again. And indeed, even the infrastructure itself is quite a luxury. Were it to be that oil required rationing, or state funds had finally dried up after decades of obscene debt, the services rendered to occasional seasonal homes would all but cease. They would be sold at a firesale price, and at least for a time the woods would go darkly quiet once again. I suspect that one day such an event may come as a permanent visitor, and those who remain will be robust and content with their precarious and feral obscurity.

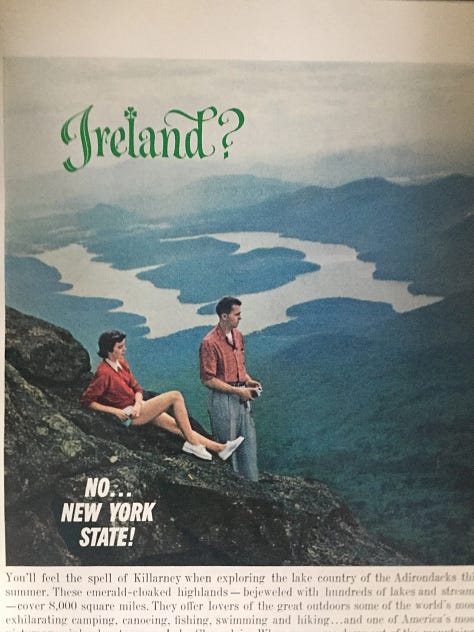

Such environments offer the American weakling a chance at remembering himself. The doggedness written into their very ecology may serve as a valuable model for him to get a sense of what is true and just, and it may inure him to beauty and holiness. Even more valuable still, it may bring him to peace with that which can be changed and that which is fundamentally immutable — about life, about the world, about himself, about God. For this land is geologically no different than the ancestral lands of his most primeval relatives; the great chain of mountainous territory spanning from the Appalachians to Newfoundland and Scotland is of one same stone. He may therefore be more at home here than anywhere else; he may have no need for a transatlantic jetplane, for the foreboding skies of old Eire linger westward to these elegantly mangled hunks of mossy stone.

There are, of course, ‘modernizers’ in the Park. They puff away at so many obscene visions, working up a gay sweat, unfurling the flags they’ve dragged up with them from the city. “A high-speed electrical rail will bring half of Wall Street here in a mere two hours! Immigrants from far afield will fill our villages with Asian-fusion food trucks and Mosques! Perhaps a gender clinic will open in Star lake!” To them, I brush them off; they are as far off the mark as Charles Frederick Herreschoff was at the turn of the 19th century. For a certain sort of person, our mountains constitute what may be as good a homeland as we’ll ever get in Old Glory, and I rather suspect that this will remain the case — for the land can’t tolerate many like them, and will slough them off as easily as a deer bristles flies off her back.

For this reason, I can scarcely care about the pissing and moaning issuing from conservatives in ‘deep upstate’. Sure enough, our great state is owned and operated by a clan of convuluted crackpots. Occasionally, they get something right — very right. When it comes to maintaining the Park as a forever wild preserve, I can commend them for choking economic activity there down to a minimum with their Byzantine regulations. For without their efforts, more would attempt to wrest this land under their plows and ugly subdivisions; they would build interstates and strip clubs and all of the trappings of the homogeneity which has retarded our nation’s spirit. While those efforts would doubtless crumble under the austere carrying capacity of such a place, it’s better for them to have never occurred lest the glorious beauty of the land be desecrated. As for the taxes and the various laws, I cannot care — one is as free on the West Canada or the Moose River Plains as they ever may be in Alaska or Montana. If I’ve got to be an outlaw, well, I’d do so with good company, for this has always been the land of squatters, misfits, and backwoods bastards the likes of which you just can’t kill — quite like the land they love.

Some who read this may not be the sort for such an obscure and Spartan manner of living. To them I say “Good day.” Pay us a visit. And should you seek agrarian bliss, remember Mr. Herreschoff as you finger the loamy black tilth and whisper to the seedlings. Every land has a spirit and character which makes you who you are. Each will make you suffer — or at least, let us hope so! — and in so doing, it will weld you to your soil, your kin, your past, and your future. It will squeeze that squirming frontiersman inside you and from it fill your cup with culture worthy of the name. Whatever story you seek to live, the land must always be your guide, and the spirit of your forefathers will propel you to create something which sputters with sublime tidings: I wish you well on your journey. God bless you.

A beautiful read

You're pretty good at this writing thing. Pretty good indeed.