Dear Friends,

A season of frustrated zeal and potent stomach bugs has swept cruelly across the North. I've been incapacitated with the worst illness I've had in years — the sort that drains all the hydration from the innards and leaves even a sturdy buck in a heap of aches and dumb somnolence. Last week was warm, and I was healthy. Optimism rose in me as the sun hit my skin, and I began to look at my rucksack with a certainty in my heart that the weak winter had yielded an early spring — and that it would be time to hit the road again this week. How wrong was I! Rime ice curled against my windows, gastrointestinal illness and snowfall ran their raid on my house and body — and I am now weak and still very much a homebound northerner in a world of winter.

Yet I have made the most of it. I re-read the piece I wrote two weeks ago — A Hitchhiker's Heartbreak — and realized that it deserved an addendum. While I was quite content with this piece and its expression of my dismay with America from the 10,000-foot view, I had failed to communicate the more personal corollary to this dismay — the specific mechanism by which long-term travel alters the spirit of a man. And so I present you this essay, which is a sort of "Part Two," titled Permanent Stranger. Thanks for reading.

Imagine a world of oranges. Naranjas. Some are green, some are wrinkled and rotted, some are royally arrayed, sun-tanned, the portrait of the heavenly citrus of Sultans and Presidents. They are in boxes, or in bags, they are in a thousand hands flinging them down at lightning speed — it is one-hundred-and-five degrees and the parched earth shimmers in the distance. Dessicated black mountains flank the picker's field of vision like resinous castles of charred offerings to an absent God — the Indians called this place "the valley of the dead." In the summertime, the daytime highs pull a blistering one-hundred-and-twenty-five degrees from the thermometer. Near dark spots on the desert floor, a tradesman's laser thermometer might read more like a hundred-and-forty-five. Thermals rise over the land, most of its valley laying dumbly below sea level. This is an irrigated land, an American Nile — I am picking oranges in the Imperial Valley of southeastern California.

Beyond the walls of the grove, the world is hopelessly dead. Here, possibility is found in canalized rivers and channels. If one's face is dirty, they need only hover over the surface of these bizarre tendrils of shimmering water to bathe in the evaporating mist on a hot day. Orange by orange, trabajaba con los migrantes, packing oranges into crates and crates into box-trucks which would be sent throughout the world for school lunches, mid-afternoon office snacks, and the breakfasts of everyone from janitors to bankers and prisoners to Governors. I was the only white man on the job, and the pay was in efectivo — strictly cash.

In such an environment, one thinks seriously about the gentle orange. It's a tree that seems to be capable of thriving in extreme heat; hardy to the worst heat-waves of America's second-hottest place so long as a delicately-managed flow of irrigation systems is allowed to continue. I ate oranges every day; I was gifted bags of them, boxes of them, I even sold a few back at the shantytown where I lived. All of us were squatters out there — where the only tendrils of water were fenced with large, faded signs that read ¡PROHIBIDO EL PASO! — NO TRESPASSING! And the only free water was the warm saline water one could get six miles away at the dilapidated Chamber of Commerce.

This was an apocalyptic world, a world where the promise of the groves and plantations had, for one reason or another — withered. All that remained were extreme marginals living in absurd poverty, a filthy hot spring, and the ruins of a long-abandoned US Marine Corps base. The police would almost never come there, and when they did, they came in great numbers, only stepping out of their vehicles in scores of men six-deep or more, guns drawn. This was the lawless West as one might envisage it — albeit with a few modern amendments. To call it "third world America" would be right on the money — though there wasn't any money there.

Next door, the Chocolate Mountains Bombing Range was active. Planes would fly overhead, dropping cluster munitions on the ghastly, arid mountains day and night. The Santa Ana Winds blew trash towards us from LA — which was, amazingly, a full 150 miles west. Often, the newspapers were only a day old. I was living in a Mexican-style mud hut, eating only oranges, hot dogs, salsa, and tortillas, and drinking only warm liquor and thrice-filtered canal water. I'd see men coming back from their raids on the bombing range, carrying aluminum fins they'd pilfered from the military base, having pulled them from the sand amid countless unexploded bombs. They'd take them into town and trade them for meth. I'd watch them straggle about the hardpan, eating orange after orange in the searing heat of the Sonoran Desert.

When I think of the word "orange" I think of what a prison language can be. The word conjures an image of the fruit with a color of the same name. One likely should think of the grocery store orange; washed, waxed, shipped, cooled, selected for shape and integrity, bred for easy peeling, sterile, inspected — a standard orange. By the time it reaches the consumer it is not only the fruit of the tree but the fruit of an enormous $655,000,000 industry and a massive state, federal, and international bureaucracy tasked with regulating it. It is the fruit of an unthinkable maze of slowly salinating irrigation projects and their ten-thousand channels and hosepipes, the fruit of the oft-hated migrantes, and the fruit of dozens of dams on the Colorado River that covered Indian petroglyphs and rare cacti and ancient settlements — dams the construction of which altogether killed hundreds of men. And it is the fruit of the truck drivers, grocers, mechanics, dispatchers, logisticians, regulators, fertilizer manufacturers, and the waitresses, oilmen, strippers, massage therapists, drug dealers, and janitors of all who keep these workers fed, lively, clean and well-oiled. The orange, as we usually know it, is not merely a fruit that grows on a tree.

Yet for efficiency's sake, one must gloss over these details in speech. One must even contort the natural reality of the orange — sun-warmed and ripe, consumed in the desert sun, with the taste of sweat dripping to the sides of one's mouth, gushing with all of the juice it might've lost in being shipped to Bangor or Brussels, unwaxed, unweighed, un-taxed, unmolested — into the idea of the orange. I am no linguistic philosopher, and am quite ignorant of the ins and outs of this science, but suffice it to say that my experience with oranges in the desert has let me to realize that the very word is often completely inadequate to describe the fruit. Indeed, those who regularly employ the word orange in their food orders, grocery receipts, and the requests of their school-aged children are trading in a stunted and largely anesthetized idea of the orange and nothing else. The natural and divine realities of the fruit simply cannot be told for the sake of clarity and efficiency in communication lest we have shoppers going on rich poetical litanies about these fruits in the grocery aisle or cafeteria line.

Perhaps this inadequacy is why poetry must exist, and yet true poetry-for-its-own-sake is utterly maligned in our era. Poetry which encapsulates the original, primordial, natural qualities of the living, breathing reality of what a word must really represent is rare — as the meme goes, ain't nobody got time for that. And truly, were a human being to employ the poetic-romantic mode in all of his speech, he would never get anything done. Worse, in a world of linguistic efficiencies and coolness to the fine-grain details of the natural and the essential — he would risk being unable to communicate with anyone at all. The pure poet would be branded as a crank and a do-nothing; his commitment to the truth of things would only be his exile, and he would be left only with an unwaxed orange and the silence of his isolation, far from the PLU numbers listing the words "ORANGE: QUANTITY: 1 PRICE: $1.29" at the self-checkouts of the others.

There is a certain "I've-seen-it-all-and-let's-just-get-on-with-it" quality to modern man that permits and justifies his use of bloodless and fundamentally anti-poetical turns of phrase. His efficiency is only the precursor to his glib pretension. He has no time for the vastness of his world; if he wishes to know, he will Google. Bums and Bodhisatvas may prattle, and poets may hawk their slim self-published pamphlets about nothing, but he has to be productive. Perhaps the modern man has earned his right to be dismissive — after all, it was not poets that got man onto the moon, but engineers who showed up to work on time and did not wander into the orange groves to weep over the juices of a lowly fruit. His world is a world where man is as a God; the lordling of his own creation, all of which was facilitated by a manner of thought and speech which delivers a thinking mind straight to the point without fanfare or distraction. Moreover, his own standing is reliant upon his adoption of these principles. Earnestness, freedom, and poetical maximalism may be flavors which he samples — if he is a charitable and worldly sort of individual — but they can never eclipse his commitment to whatever ideas facilitate his success, ambition, and ultimately his social acceptance.

It seems fair to say that the human brain is adaptationally adept at doing practically anything necessary to avoid being "voted off the island". Whatever is necessary for social acceptance — no matter how dismal or intellectually inconsistent — is paid as a form of "rent" for this privilege. Logical incoherence is a form of currency in the social arena, as is the anti-romantic materialism of the modern commerical society. Evolutionarily speaking, there are fantastic reasons for this: To be branded as a subversive crank, a do-nothing dreamer, or a lunatic may well have been a death sentence in many primitive societies who found themselves situated in harsh environments requiring social cohesion for survival. And in the early eras of agrarian civilization — the man who argued against the use of the plough or the doctrine of the Church may have seriously forfeited the coming winter's meals. Far better to accept whatever status quo feeds you, most must've reasoned — a rabble-rouser, heretic, or dreamer is liable to starve.

Let us be realistic, says the brain-stem, and so it is that eras of great swinging romance and freedom tend to be only flashes in the very pans that will be used to clobber the revellers tomorrow, and conformity is the currency of the civilized social man. One departs from the shared illusions of his compatriots purely at his own risk.

And so it is with freedom.

Ignoring well-intentioned advice may quickly becomes normal to the one who takes to the road. As I neared my sixteenth year, I vowed not to get a license, for I had heard another boy complain of the cost of his truck. When I asked why he had a truck, he said he needed it to get to work, and when I asked why he had a job, he said he needed to pay for his truck in order to get to work, which he despised. This tautology struck me as so absurd I could not imagine lowering myself to this level of obtuse and irrational Mongoloidism. And so it was that a natural skepticism of prevailing wisdom began in me. Others said to go to College — in order to get a job, and to get a job in order to purchase luxuries which are demonstrably unnecessary to human life if all of human history prior to the 1950's is any guide. It became clear to me that if I could radically simplify my needs that I would essentially have no reason to subject myself to various indignities and logically inconsistent notions of human ambition. If I could develop my own ambitions independent of the status quo, perhaps I could discover things that others had no way of accessing or understanding — and after all, I'd grown up on a steady educational and media diet that glorified pioneers, explorers, mavericks, and those who thought outside the box.

In time I was skeptical of sedentary life and the emergence of civilization itself. I grew skeptical of clock-measured time and calendars, of most forms of technology, of Western musical notation and tone (virtually all of which is contained within a fraction of the sounds that are audible to the human ear), and even of language itself. I refrained from any interest in movies, television, sports, video games, cars, electronics, jobs, money, religion, politics, or practically any other widely-legible form of behavior. I wanted to be nomadic; I wished to observe and imitate the living world one encounters in wild places, to be comfortable in solitude and complete silence — to meditate such that even my own mind could dwell in an entirely wordless realm of utter presence in the immediate 'now'. The use of everyday nouns began to irk me, even to the point of internal anguish at the ugly, quick linguistic jabs with which people spoke so roughly and without faith to the living truth of things as they are in their untrammeled form. I only carried a flip-phone on my travels (which I usually kept powered down) because my mother tearfully demanded that she have a way to get a hold of me in my journeys. Besides this, I made no other concession to a world that seemed fraught with dishonesty, boorishness, and logical inconsistency.

I absconded to an alternate world; a realm in which I had banished compromise. This is to enter the desert; it is the metaphysical universe of the inmates of insane asylums and the contemplatives in mountain caves. It is a place of ecstatic madness — a complete wilderness in which the shared illusions so often requisite to human society are turned to smoke, forgotten, and ignored.

And in short order, those who venture there are forgotten and ignored. Like a curl of smoke, such a man is nobody. His extreme commitments to the sincere and earnest poetry of the present moment gobble him and hide his entrails; he is illegible to all, a theatrical vessel met only as a sun-tanned, bearded ghost. Among men, he may quaff spirits, he may abscond into stupor, he may tell lies and shapeshift, he may spend weeks in silence, solito, watching the stars. And to him all words are dead — like receipts in the mud, only trivial things, and he can say nothing even when standing before a crowd. Yet the crowd carries him through the streets and he is crowned in wreathes, lauded as a stripling wiseman — and then he feels the hangover, the jab of government-issue boots in his sleeping ribs, the darkness under his eyes, the sodden humidity of the humorless planet. Such eras, thrilling and despondent at once, kill a man completely, reducing him to a seed. These eras are the punctuation between generations of man, not as a man, but as a culture all unto himself. When he regrows elsewhere, he will be different. If it is bad — he must go and die again. And it will always eventually get bad again.

To put it charitably, the foundational building block of human society, culture, and community is the shared agreement. If I and a man named Gerald sit at a truck-stop on I-70 on a bench with a statue of Ronald McDonald — we know we are not sitting next to a demon who may come to life if we say the wrong thing. We know that inside the truck-stop, there are bathrooms, coffee, and probably a few cheerily weathered old ladies at the counter selling chewing tobacco and lotto tickets. We know that if we go inside, put a twenty-dollar bill on the counter and say "pump six, please," we'll be able to go to a place marked "6" and gasoline will spray out of the nozzle wherever we like — but we agree we'll keep it in the tank and not on the kids or the dashboard. If I decide that Ronald McDonald is a demon who will be woken by the man commenting on how awful his burger was, I will violate the agreements. If I decide that by "coffee," he means "boiling human blood," and express disgust at his desire for a cup of it — he will think I am insane. If I spray gasoline all over his cousin's arm in an effort to "protect him against the demon over on that bench," he may physically attack me or call in men who may attack me on his behalf.

Without shared agreements — we are insane.

And yet without departure from at least some of the shared agreements — one could often just as well call them shared illusions — innovation simply cannot occur. Frontiers cannot be settled. Exploration of any kind becomes impossible. When a Bostonian slum-dweller in 1851 proposed a venture to settle in Oregon Territory, his mother may have been appalled and disgusted to the point of tears. She may have wondered if he was crazy. Such a man's own name may now very well be the name of a bridge, or a burger restauarant, a hotel, a mine, or even a city. His children may be wealthy businessmen or University trustees. And likewise the man who first imagined that he should pull upon the teat of a wild bovine and consume the resulting liquid — or the one who later would go on to let this fluid sit for months or even years to produce cheese — must've been considered absolutely out of his mind. It is therefore fair to submit that the job of the innovator or explorer is to venture into the realm of insanity — at least a little bit.

If he finds something good, he may establish a new set of norms in his pioneer settlement which will soon consider new things to be insane; or he may demonstrate that what began as an insane departure from social convention has actually yielded a most useful or delicious invention which will no longer be considered insane. Such men are welcomed back into the world of shared social agreement easily; their eccentricity is viewed as a fascinating boon, and a benefit to all.

The ones who venture completely into this realm find insights which are useful only to the hermit. None of them can be forgotten; none of them can be erased. Each is like a tattoo; provable only within the mind of the beholder or viewed by adventurous or sympathetic types with curiosity, disbelief, or with exclamations regarding its marvelousness or its abject lack of worth. The fruits of his own endeavor start to go rancid; they start to burden him like ingots of lead. He has opened up his veins for the sake of these fruits, he has dragged his own corpse across the salted hardpan for their sake — and yet they remain completely illegible and preposterous to every soul he bares them to. Like inedible spices, gold encapsulated in coal, rotten specimens of a harebrained expedition, balding furs of unknown animals, broken scrolls by feeble-handed calligraphers — he has secured his useless treasure as an unthinkably straining and byzantine exercise in doing nothing.

I carried these elaborate weights with me into the forest of my own home village, exhausted, dead to the world.

My cousin told me: "You pulled up at my house at three in the morning in a ragged-ass Jeep, you must've hitchhiked, then you walked into the house and slept in front of the pellet stove for almost three days." He related the tale to me with a level of seriousness that bordered on the funereal — I had no memory of the occasion whatsoever. I had arrived home in a true fugue, my half-decade experiment in insanity only dimly understood by my closest friend, without memory of how I'd arrived. And in only a few years, I would jump into the most profound 180-degree turn any who knew me then could've imagined. I would dive directly into the most extreme expression of shared social agreement imaginable when I would swear an oath, shave my head, and finally in a gigantic auditorium at the sides of a hundred other men in blue suits scream — "I AM A COASTGUARDSMAN // I SERVE THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES // I WILL PROTECT THEM // I WILL DEFEND THEM // I WILL SAVE THEM // I AM THEIR SHIELD ..." I shouted it so loud and with such extreme conviction that I nearly passed out and fell on the floor in a paroxysm of patriotic panic.

To this day, I cannot imagine a more crystal-clear social agreement than this.

The moment was still another death; and yet the leaden ingots of my traveling years — and all their intricately petroglyphed memories — had not evaporated. I sloughed them along with me, the entertaining oddball, the too-old-for-his-rank eccentric. A clownish bard, stiff-lipped on the liquor in port town tavern rooms and yakking about Nevada uranium and nose-ring wearing homosexual midgets in Tennessee; praising illegible things as if living inside of my own joke, still firmly in my own desert as I faked miles of line out on the decks of a Michigan icebreaker. Solitary and silent in the deep holds of the vessel crashing through the frozen freshwater, I fed the caged creatures kept at the high halls of my spirit, vomiting as I did so as the ship twisted sideways over the Edmund Fitzgerald. Later: a chickenshit desk-job in New Orleans, men talking about sports, cars, phones, titties, Bitcoin, guns, television, and panic attacks on absurdly expensive dates with stiff-lipped wenches feverish for the Emperor's scrip and sovereign coin. I bought track pants and a beat-up used BMW, I tried to play along — I wound up drinking along. My ex-girlfriend's abortion came after three-and-a-half months in solitary "quarantine", where we drank once weekly in groups of six between plastic sheeting, and the pity-eyed bartender poured us the "two drinks" we were allowed as full pintglasses of vodka. Like Solzhenitsyn on a freakshow bender or Raskolnikov in clown makeup, I could only schlep along, wondering how I'd been mired in this abstruse web of Soviet non sequiturs. Dominus Vobiscum was the clarion call which occasionally reminded me that I wasn't dead yet — the Priest gesticulating, the incense wafting, the tender Man on the Cross...

And one day I awoke and had no reason to shave my face. Yards of navy-blue fabric lay crumpled in a bag — the streetlight shone on the beercans and cigar ash of my very own porch. I believe I owned the house — that's right, I did own it! Two weeks had gone by and I hadn't spoken a word out loud. The paperwork was in the mail — DONE with the US Coast Guard. Covid, remote work, mom's terminal diagnosis, two-hour-one-way bus commutes from Brooklyn to Staten Island, server rooms, orders to do nothing, days spent in uniform on Twitter and thinking of Ted Kacyznski. Bedside Rosaries, too — and voices on the radio speaking in French, a thousand cluster flies and an unmowed lawn and the beady eyes of a small-town waitress wondering what the hell I do for work. All of it was over, and I was here again, doing nothing, alone.

The respect I'd won by this big experiment was a perverted figment, an ephemeral thing, a respect-on-the-installment-plan type of scheme. The lady who'd opened the door for me at the post office and said "Thank You for Your Service!" brightly back then might today dismiss me as a nut-case, a blowhard, a do-nothing. I took a look around my shabby, ancient, tiny house — my estate — and realize that everything is illegal, and I've just set four years of my life on fire. I'm rounding the bend to the age of thirty, I've seen the country, I've sailed the seven seas, I've plunged into the River Styx and gone to dive-bars in Sodom and to Hoovervilles and acid-dropping naked hot-springs and done pushups in pigeon-shit at Uncle Sam's facility where they all say hell-yeah but for whatever reason they just can't kill me. Like the old bumper sticker reads — TOO WEIRD TO LIVE, TOO RARE TO DIE.

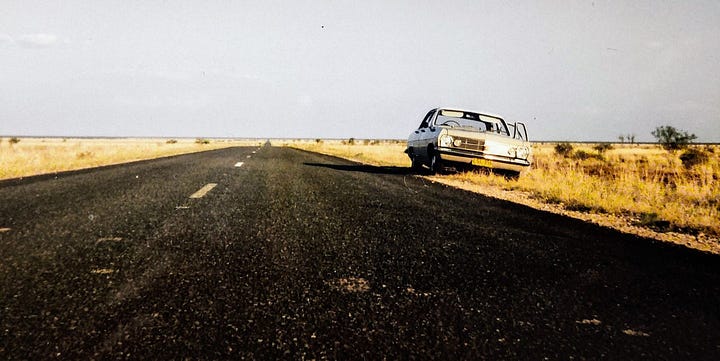

And just like that, I'm in the ‘desert’ again, back in the world with the monks and the mystics, back into the boxcar they use to send the nutjobs to Timbuktu. Back in the Coast Guard, an orange was an orange, now give me an "aye aye" and get your sorry ass back to work. Now, again, I'm dreaming of oranges and the same old deserts they ever grew in, and I'm back on the same old trail I ever was — a stranger, forever, back in my homeland, completely incorrigible.

At the end of it all, I'm staring out as the snow falls and wondering just when the hell I can get out of here and get right back to it. I'm incorrigible, and I'd be lying if I said it don't hurt a little — but that's just the way it is.

>There is a certain "I've-seen-it-all-and-let's-just-get-on-with-it" quality to modern man...

Yep, that whole paragraph's me. I'm not the sort of person who could be any different. I appreciate your writing---it may as well be written from another world.

.. wild ass ragin .. where lexicon runs free ..

with words & phrase as polar bears..

ranging through our streets..

🦎🏴☠️