Corrugated plastic signs shake in the wind like the delirium tremens of a sickly drunk; their cartoonish words slap against the salty snowbanks, making unthinkable promises. Malone, New York is a depressed town, a squalid settlement at the ragged edge of American civilization, separated from Quebec only by a brief and mostly un-peopled realm of spruce and maple. Like many Upstate towns, Malone's salad days passed generations ago. Droves of old-school families from the area have torn up the stakes and headed to the Sun Belt, where jobs aren't so hard to come by and winter is either laughbly brief or entirely unknown. The remaining young people are seldom courted by any employer, institution, or benevolent force of any kind — they are a cynical bunch, rarely more than one misstep or stroke of plain old bad luck from unemployment or addiction. To say that their prospects are bleak — at least by mainstream American standards of success — might be an understatement.

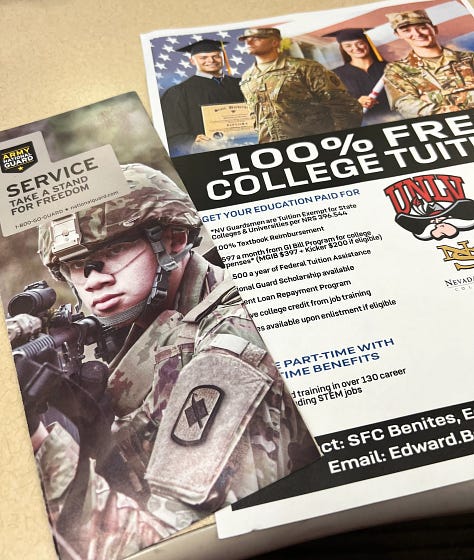

Entering Malone from the west on Route 11, right at the intersection with the Stewart's gas station and the Jreck's sub shop — those venerable instutitions of Northern NY — the corridor of plastic National Guard recruiting advertisements is almost jarring. In this landscape of defeat and dead-ends, dozens of signs bearing the words "FREE MONEY FOR COLLEGE" in bright letters feel like some kind of a trick to any sober-minded adult. But much like the signs on strip clubs that say "GIRLS, GIRLS, GIRLS" or the neon hanging high above casinos proclaiming "Jackpots as big as $115,000!" — the promise of "free money for college" sneaks into the mind of the despairing young fellow through the back door, defying rational scrutiny and beckoning him to pick up his telephone and make the call. When things are bad, any whisper of a turnaround enters the bloodstream without resistance, and in time, a young man from a town like Malone might be signing his name on the dotted line at the Military Entrance Processing Station in Albany before finding himself under the bright fluourescent lights of boot camp.

When I joined the United States Coast Guard, I did so almost as a strange sort of practical joke. I had been dating a rich Jewish girl from suburban New Jersey at the time. She was a sullen and literary type; the sort of woman who is a genius in the most purposeless way, for her intelligence seemed to obstruct any possibility of happiness or contentment. Such types tend, especially in recent years, to take strange measures to slough off their inpenetrable ennui, and she took to accepting a courtship from a man who was formally homeless and itinerant — a bearded, scraggly man who at the age of 25 had never worked or filed a tax return. We hitchhiked to New Brunswick, where by the rocky coastline I promised to build her a cabin in the woods, and to this, she offered a slight smile which seemed to indicate that such a gesture might somehow alleviate her existential anguish. Then she flew to Poland for a final literature study, and I returned to my home village to build her a tiny cabin with my last $1,900.

When she returned, only the most primitive structure was completed; a dirt-floor shack sited on the side of a rocky ridge on my uncle's hardscrabble fifty acres. It had a woodstove and an outhouse and a loft with a mattress. It was a ten-minute walk from the road on a turkey trail of a path — a twenty-minute ski in when the snow was deep. She arrived in January to find the cabin — which was barely 100 square feet — roasting warm as I minded the fire of pallet wood scraps I'd gotten from the roadside out in front of a local factory. We hauled everything in on sleds; books, rice, lentils, water, beer, onions, all of it towed by the both of us on cross-country skis. The trail involved crossing a small pond which was easy enough to cross when frozen. But on warmer days, it became a hazard that threatened to overturn sled-loads of precious groceries into the water. This was a far cry from suburban New Jersey — and by no means the quaint "cottage-core" lifestyle depicted by "off-the-grid" social media.

My own sensibilities at the time were essentially third world. I had lived in railyard shacks and Mexican mud huts, slept under tarps, pissed in jugs, and rationed my water on high cuestas in the Arizona deserts. I had been homeless in wintertime in the Berkshires and had shat over the side of my old "shantyboat" in the swamps of New England. To me, the cabin was high livin' — but to her, it was a miserable dump that only intensified her vague and tragic angst. In the spring-time, she gave me a talking to down in my uncle's swamp, sitting me down on a stump that had been sawed into a rough chair. Years before, my cousin had sculpted it when we were cutting firewood, laughing as he remarked; "I bet no one will ever sit in it, but who the hell knows?"

As I sat on the stump-chair, she made it clear that our foray into off-grid, dirt-floor cabin life was not acceptable to her. If I wished to keep her with me, I needed to do something. Her plea was nonspecific in its verbiage and yet at the same time completely clear — if I wanted to stay with her I needed to get a job. It happened to be my birthday that day when absent-mindedly, the words burped out of me almost as a bizarre experiment — "I will join the Coast Guard." Six months later, I went to boot camp in Cape May, New Jersey. "Money for college" scarcely entered my mind until I was briefed on the Post 9/11 GI Bill at a class during Basic Training.

But in the course of my service, I found a large majority of young seamen to have enlisted almost exclusively out of a desire to obtain the mythological possibility of a free college degree. None of these fine young guys seemed especially intellectual, and, when pressed about what they might like to study, most answered along the lines of business, computer technology, marketing, or some other credentialling for an entrance into white collar society. In almost all cases, their desire for a degree was more or less completely driven by the desire to get an easy high-paying job. I don't believe I met a single enlistedman with a penchant for the Liberal Arts, nor any prospective veteran student with almost any classically intellectual proclivities whatsoever. To them, college was a glorified trade school for a sleepy-eyed class of soft-handed desk jockeys with big, fat pensions — the sorts for whom their toughest daily decision is whether to get the capiccola with ham or the hot wings on their hour-long lunch breaks.

This pie-in-the-sky vision of modern American affluence merely required a college degree as one's entry ticket, and in an era of rising tuitions, enlisting for a four-year hitch seemed to be the most sensible prerequisite for those born into the economic class that is too poor to pay for college out-of-pocket and too rich for lavish need-based financial aid packages. For veteran-students from the poorest bracket, the GI Bill merely fattened an already-expansive network of student aid — most of these could, with a bit of shrewdness, actually derive savings from the many streams of cold hard cash ladled out onto both GI Bill recipients and the poor. Yet this world of credentialling and bank transfers struck me as almost cartoonishly cynical — the notion of "education for education's sake" seemed to be an afterthought at best. Most often, the idea of education as a vehicle for the betterment of the mind and spirit of the student is entirely shrugged off, if not actually beyond the grasp of many prospective students. If such heady abstractions are ever mentioned in a discussion about the purpose of college, they are quickly followed by talk about "employability" and the job market — scholarship is almost never seen as an end unto itself.

Though I joined to keep the girl, she didn't stay. When I got stationed on an icebreaking tugboat on Michigan's Upper Peninsula, she declined to accompany me. A heartwrenching "on-and-off" long-distance relationship ensued, and meanwhile, my cabin sat idle, succumbing to mold and rot as the rough humidity of Upstate's seasons took their toll. Many old friends were shocked by my decision to join, and we drifted apart, while my enlisted compatriots were virtually all much younger and difficult to be close with. All I had now was an enlistment obligation in the era of covid, and I watched many of the young men who'd joined for the "free" money for college darken as they found themselves pulling soaked corpses out of bayous after hurricanes and doing suicide cleanup under inner-city bridges. It seemed to be that our GI Bill benefits were not by any means "free" — that perhaps the promises on the plastic signs on the edge of rusty towns like Malone were just as deceitful as those hanging above casinos and topless bars. And us Coasties were the lucky ones — while I sat in quarantine on a military training center and some of my boot camp buddies scraped paint on ships in the pacific, many of those tantalized by promises of free college were being shot at in the Middle East. Some of them would be disabled for life. Some would even perish.

From this point of view, the post-college receipt of a comfy, high-paying job takes on an almost religious quality. For some, it becomes the sole upside of a long, dark journey through service to Uncle Sam. As the young seaman pukes into the bilge in the screaming engine room of a ship in violent storm surge, he consoles himself with the thought of hot college chicks, fat '“Basic Allowance for Housing” checks, keg parties, and the eventuality of a nice office with a window.

The Admissions office at the State University of New York's Potsdam campus looked like a strange combination of a two-star hotel lobby, a high school guidance office, and a psychiatric center waiting room. Motivational posters hung on the walls; a middle-aged woman's neck flapped as she typed, her eyes heavy with the somber look that State employees often have. Though it was a non-holiday Tuesday afternoon when campus affairs ought to be in full swing, the college seemed devoid of life — as though it were somehow still caught in the pandemic era. My fiancee and I were motioned to sit down in one of the plush chairs next to the faux fireplace and in a few minutes, a blue-haired woman about my age came in to receive us. As I sat down in her office, her eyes narrowed in on mine, and with a smile, she asked point-blank what job I wanted.

I stammered, delivering a vague answer — I had not prepared myself for the weirdness of this environment, nor for the chasm of difference between my own conception of education's purpose and her own. The entire environment caught me off-guard; the lifeless campus where only a handful of lost-looking provincials wandered, the Holiday Inn decor, the extremely pointed and perfunctory opening question of my interview.

"In so many words, I suppose, I am a writer, and I find it a little hamfisted to study writing itself; I guess I am mostly here because I have the GI Bill, so it is free, and I live nearby. I figure I might be able to enrich my mind by doing a little school. I couldn't care less about money, careers, stuff like that — I guess you could say I'm eccentric."

She was flummoxed. Her unspoken job title as a broker for white-collar credentialling services was somehow undermined by my flatly stating I'd like an education. While I have absolutely nothing against State Colleges, nor anything against the idea of white-collar credentialling per se, I was feeling a strong sense that I was personally terribly mismatched to the prerogatives of the instutition I'd come to visit.

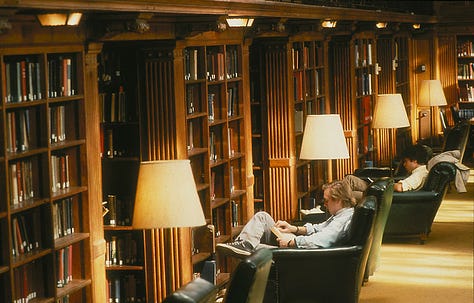

On the other side of town, I visited Clarkson, which was a bit better; the admissions counselor seemed to understand that there might be the occasional oddball student who'd inquire about merely educating himself without regard to his "earning potential after graduation". The moulding on the ceilings was ornate, the fireplace was real, the couches were leather — and the people did not look quite so cookie-fed and dim-eyed as the state employees over at SUNY.

"Our humanities program is small, but robust," the man declared, seeming to understand that academic robustness was what I was after. He inquired about my writing, and in time, we were discussing my years as a traveler. Instead of seeming confused, he seemed pleased — that perhaps my attending Clarkson would be a mutually beneficial arrangement; that maybe Clarkson could use a little bit of my 'Liberal Arts mindset' for the sake of balance at his institution. I left feeling encouraged, though nonetheless a bit shaken by the contrast between the two schools — and the fact that even at the better of the two colleges, my simple hope of utilizing my GI Bill for my own academical betterment without regard to my "employability" was still seen as odd or eccentric.

Meanwhile, employers seem to be backing away from degree requirements. A recent survey by intelligent.com has indicated that more than half of American companies are abolishing their degree requirements in at least some positions; more than half said they'd already done so this year. College enrollments have also declined — they are 14.3% down this year from their peak in 2010. And since 2016, ninety-one American colleges have shut down or merged with another instutition, with many more closures on the horizon. Still more deeply financially distressed schools are floundering nationwide as the vultures circle overhead. While a chorus of voices in higher education bemoan this shift and view it as a fundamentally negative development, I am of the mind that this is probably a fantastic thing for education on the long arc of time.

The decreasing popularity of the Bachelor's Degree probably also has a great deal to do with the US Military's recruitment crisis, for better or worse. When degrees are no longer a sacramental article of religious faith in getting a "good job", the "free money for college" pitch stops seeming so lucrative. This is especially true as most of those who are warm to joining the Armed Forces tend to skew conservative — and the prospect of attending school can seem downright unpleasant to many after four years in the military, when most colleges seem to have lately "gone woke".

I suspect that most thinking people would agree, at least partially, that the relatively recent transformation of colleges into credentialling mills for midwit white collar workers has been a disaster. I am hopeful that as colleges reliant on this model see declining enrollments, a handful of particularly dynamic institutions will rise to meet the need for classical "education for education's sake" type programs. Once higher education is again decoupled from occupational credentialling and is mostly the concern of a small minority of intellectually gifted students, society at large stands a good chance at recovering from this recent era of intellectual decline.

We traded our intellectual class for legions of ditzy psych majors, airheaded business students, Marxist grifters, and a mind-numbing pile of worthless debt, and it's been a damnable failure. As employers shrink back from 4-year degree requirements, perhaps we can overhaul academia into something worthwhile again and as a result, rescue American society from its presently dismal state. Maybe this is an optimistic view, but I frankly applaud the conditions leading to enrollment crises and financial stress for colleges focused on 'vocational credentialling'. I think good things are coming in our universities, in spite of how bleak things presently seem.

For now, those for whom the Post 9/11 GI Bill benefits are on the table will have to tread carefully. This great gift can feel vaguely burdensome to those for whom “education for education’s sake” is a life prerogative, but nonetheless, it would be foolish for veterans not to use those benefits. While many are using theirs at trade schools, union apprenticeships, CDL schools, and police academies, those who are called to an intellectual life will simply have to make-do in a collegiate environment that is still focused on credentialling. Truly, the promise of “free college” is a strange one in this era of change in higher education.

The "education for education's sake" folks of today are either autodidacts or else so-called, and pejoratively so, "career students." O, the tragedy! the horror! of a person enriching their intellectual and interior life...and not for monetary gain!!

It may be that God has sent you to make Wisdom's way straight in the universities, and here you are on the edges of society, the Substack wilderness, preaching the Gospel of True Education and baptizing them into a better pedagogical way. I'm thankful for your optimism re: the future of universities and I hope that it comes to pass sooner rather than later.

Has anybody commented on the size of that tub for that tiny shack!? What luxury!!