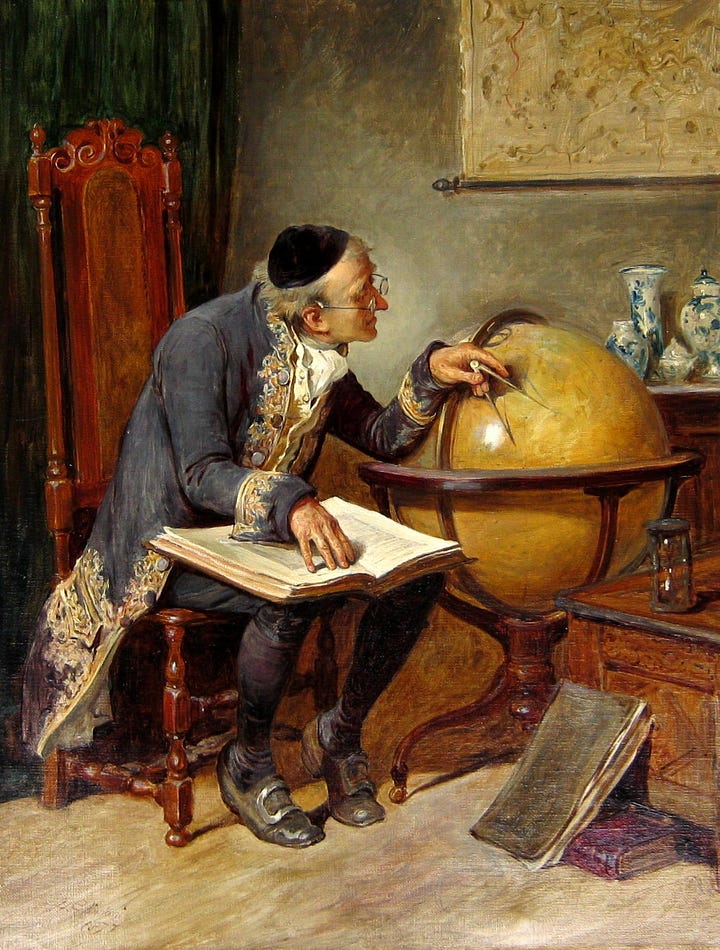

The geographer is an anachronism; he is no longer prized by royal courts nor is he of pedigreed employ. His trade is as apocryphal as that of the lamp-lighter and the alchemist. To sit jolly-faced behind leather-top desk, leafing through paper cartographic maps and pawing at demographical tomes by candlelight is these days to engage in a droll bit of historical re-enactment. The fade-to-black of the geographical arts has proven to be a ghastly development in the long story of the Western intellect; now, pencil-pushing techies push drone-based Geographical Instrumentation Systems, running raw data into voidlike computer programs which fail to impart on their users any of the human dramas of place. Insectoid robots fly through the hills, analyzing remote ravines and morasses with laser light — remnants of old mills, hidden moonshine stills, pockets of rhizome-laced loam and acidic peat, all quaint roosts for poets and hermits alike: all chalked up in the data as "physical phenomena within the margin of error" and little more. So thoroughly has this digital malady colonized the venerable study of geography that when I enrolled at State University twelve years ago to pursue a B.A. in Geography — I was informed by the bursar on my first week that the program had been discontinued due to "post-graduation marketability concerns."

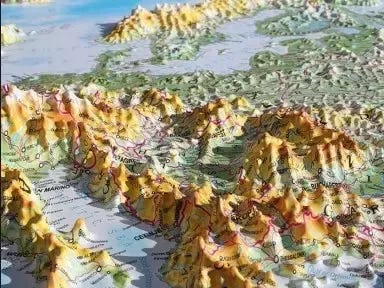

From my earliest years, I grew to treat maps with an extreme reverence that bordered on worship. It was not strictly the content of the maps that captivated me, but in particular, my interest lay in the form of the map. The very existence of cartography as an art calls everything we know about visual human expression into question, especially in the age of literacy. The map is simultaneously a book and a painting; a drawing and a poem. It contains information that can be read and yet its lines never comprise so much as a single paragraph or stanza. The cartographic display is artful and even expressive — and yet for it, even the most primitive maps make at least a minimal attempt at precision. More than any of this, however, is the implicit superstructure on which the map rests — the knowledge that someone had to go out and make it. Men gazed out at the world with wonderment — that commodity which has been in such short supply in our time — and it drove them nearly mad. And so they set off to make maps.

So mad were they that many shirked nearly every other duty of earthly life for the investigation of isolated regions, carefully taking inventory of the good earth. As they went, their expeditions sharpened their souls, steeping them in local flora and fauna and human culture. They set off on grand journeys to map the earth, steeling themselves against hardship after hardship with incredible resolve; but in time, many fell under the spell of distant worlds, mapping themselves — understanding a secret metaphyiscal cartography known only to those who take such journeys.

Such journeys call the reader of the atlas to make an inquiry into himself. The physical world described by the map is real — one could, in the vast majority of cases, go out and make a survey for himself of nearly any nook or cranny of the earth, especially these days. As the budding geographic voyageur ponders this reality, he begins to inquire into what it'd take to get there. Svalbard, Sable Island, Rub Al-Khali, Navassa Island, Utgiavik, Franz Josef Land, Tripoli — every millimeter of the paper splayed out upon one's desk calls the mind to another plausible journey. Serious consideration of these pathways calls the mind to further inquiry; could one stomach the gut-wrenching bushplane ride to Qaanaaq? Would the rough and hazardous seas of the Drake Passage drive a man to madness as he makes his approach to the glacial cliffs of Tierra Del Fuego? Looking up from the map, a man with an explorer's mindset might look up in wonderment not merely at his own deficiencies but at the awesome diversity of the wild earth. A lifetime of study of the physical earth and its human geography would, to my mind, make a believer of even the most hardened atheist — especially when coupled with the voyaging that would inevitably accompany such a study.

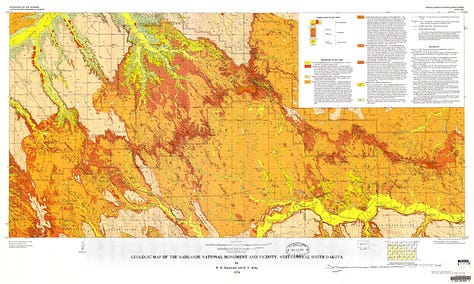

The need for expeditions is made obvious by the great frustation of any natural-born geographer; there is a very real and very intense limitation to the geographical knowledge one can find at his own desk. Laying about in the far stacks of university library basements, one finds the information they're aiming for — from 1982, 1951, 1904, etc. Old maps of Rhodesia and the USSR lay in dusty somnolence between ancient and rarely-prowled stacks; in this regard, they call to mind the temporal realities and limitations of published knowledge. One can see the cod exports of the Dominion of Newfoundland in 1910 on the yellowing pages of a forgotten tome easily enough — but one can hardly imagine from his library desk the life of a present-day Newfoundlander as he navigates his trawler upon the belligerent seas of the North Atlantic. Even if his almanacs are of recent marque and contain the most up-to-date information, he winces as he realizes how insufficient his information really is. The entire domain of geographical study consists of suggestive whsipers in the form of data and visual displays; tempting their student with so many hors d'oeuvres which threaten to become meals if only he will exit his office and make the trip himself.

Of course, were it to be that any academical blockhead traversed to the obscure corners of the earth in search of more updated information on cod fisheries (or some other number), he'd likely leave his destination with a great deal more than numbers. If he made his voyage correctly, he may come to the dim recognition on the train home that he'd never gotten the "updated information" he initially came to find — that such information was, in the end, an afterthought. This is because — in flagrant contrast with the new geographers and their computer-based mentality — lands and their people are not merely phenomena to be measured. Neither are they automata remotely suited to rational grasp; all but the most obtuse practioners of the geographical arts may find that by the end of their careers, they've resigned to writing poetry or mumbling prayers — their hearts levelled by the vivifying and storied living realities taking place at every corner of their studies. There are places — most especially the remote places — where one cannot observe; the visitor is sucked up into them as a living appendage, gripped whole by the scenes of daily life and the biographies of those who stoke the fires and pole the coracles along their alien shores. Some immeasurable thing is alive in them, and in spite of the best efforts of even the most persistent and finnicky gatherers of data — the map remains a mere suggestive visual and little more even after one ventures to the lands it wordlessly displays on the paper.

Now, the man who aims at such a vocation has been starved of any hope at achieving the glory of his forebears. The royal courts that once employed geographers and their teams of voyageurs have been ransacked and turned into lifeless tourist displays; next door, sprawling and ugly parliaments chortle with ghastly men to whom cartographic poetry is unknown — the sorts of creatures who might glibly state that "the world has already been mapped". Absent any structure that could confer legitimacy or gainful employment upon the would-be geographer for his trevails, he descends to the level of an outlaw — he either capitulates to the geomatic panopticon or is relegated to the status of the vagabond.

This is a truth I know all too well; I’ve lived it myself and I am certain I am not alone. Genius octogenarians slouching upon chairs at bum-feeds and libraries, fingering the vellum of cartographic apocrypha one volume at a time — residents of squalid tenements and subterranean caverns dug in the banks of foaming rivers, anxiously devouring virginal tomes detailing obscure foreign histories. All of them, unemployed geographers. They walk and wander or lay back at libraries, half-doddering in their disgruntlement and poetical hopes for the faraway shores — listless and shunted from the corridors of relevance, having missed the golden age of their forgotten craft by mere generations; unemployable. A vast and seldom-noticed contingent of tragic men seem to have been born for an era of exploration that — allegedly — has come to its bitter end.

This purported 'end to exploration' is not for lack of worlds to explore, of course — it is merely another cruelty of this era quite akin to the fade to black of poetry. That the poetical arts have sunk to the level of a niche interest says nothing about whether poetry is actually dead or whether its universal import is actually in question; to the contrary, it is needed perhaps now more than ever before. No, to the complete contrary, poetry has been ripped from the hands of mankind by a glistening technological Leviathan which renders the conscious brain into a trembling, worthless mesh of ravaged neurons — this, I contend, is the sole reason for its stunning absence in the modern West. Shimmering loops of video and sound mouth this inhuman system's triumphs; all of them bruising the spirit such that poetry is only an unrecognizable approximation of the sentences modern man reads in technical manuals — its stanzas make the Man Without Qualities haughtily suggest that their author go on and "get to the point".

The lamentably obtuse claim that the world has already been explored is no different. It is borne of an extreme and hyper-modern narrowness of mind; etched into its underside is the bleak notion that "if it cannot be measured it does not exist." True enough, the world over has now been measured; our airborne laser-light technologies could measure the remotest crevice of the most inaccessible glacier in a few hours if the powers that be wished for it to be measured. But mere measurement is only a minute and rather hamfisted corollary to the geographer's actual purpose — to journey into the land as it now is; to offer oneself up whole, plunging inescapably into the bloodstream of its colorfully peopled contours. So much has changed since the dawn of industry and the internet that there are vast quadrants of the world which must be re-explored and re-charted again — that "it has already been done" would only seem relevant to victims of a complete and tragic spiritual defeat. Moreover, whether the world has already been explored or not is irrelevant to the fact that exploration has become a genetic imperative for a great many human populations. Many of us were simply born to do it.

In his Substack titled Grey Mirror, Curtis Yarvin reflects on hunter-gatherer populations, whom he has termed "autochthonous" peoples. He writes:

" ... a lot of humans of recent autochthonous descent [...] are indeed failing to thrive. They seem to need more freedom and challenge than agriculture-adapted populations, probably because tending crops is boring as hell. [...] for those without the evolved Sitzfleisch to endure boredom, man has only alcohol. The paradox is that while urbanized observers from Tacitus to Fenimore Cooper, too often by accident, portray a more ancestral population as an inherently superior race of lords, pre-agricultural populations are like Italian racecars: specialized. They do very poorly, except in their adaptive environment. Yes, this is probably a DNA thing."

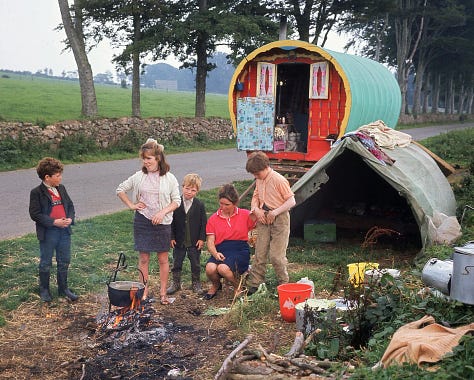

For my purposes here, the phrase "autochthonous populations" can be used interchangeably with hunter-gatherers and those with a natural-born and inescapable proclivity for exploration, travel, vagabondage, and hands-on geographical study. Individuals of such a pedigree have an overwhelmingly hard lot when forcibly incorporated into sedentary civis — and the former practice of creating legitimate and paid roles in polite society for them as explorers, geographers, and colonists was perhaps their only saving grace for many centuries. As of late, these roles seem to have dwindled to the point of collapse. Now, one can "tend their crops," growing tidy fields of time-sheets, mortgage statements, and paid days off — or they can exist in a profoundly marginal and eccentric niche.

Years ago I might've rankled at the phrase "blood memory," thinking it to be a phrase that would only get play among nerdy, kilt-wearing neopagans or among Blut and Boden fascists. This changed when I made contact with my father — a man who has never laid eyes on me even once, and whose name I did not know as a boy. I had not a whit of information about him for my first twenty-five years of life — years during which my unquenchable desire for world travel had been totally apparent from my earliest years of youth. By the time I spoke with my father, I'd hitchhiked more than 100,000 miles in the continguous US, Canada, and Mexico and was still living a decidedly un-settled life as a sailor. Our first call took place during a covid quarantine, when I was a military fireman stationed on an icebreaking tugboat in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan. My seabag leaned against the door-frame — a new sort of backpack to live out of — as I listened for the first time to the voice of a man whose genetic content was irrevocably present in my own flesh.

"What have you done with your life?" was my first question. He answered quickly and with a voice of certainty and pride — "I have been on the road for almost 40 years." The man was and continues to be what some call a "carnie" — a circus-man, traveling town to town all summer, putting on shows and erecting Ferris wheels and game booths for meagre pay. Carnies have a reputation as a dysfunctional, semi-outlaw bunch — to "run off with the circus" is almost a proverbial expression of failure and marginality, but to my father, he is proud of his vocation quite nearly to the point of tears. He met my mother at the largest Renaissance Faire in the United States, where he'd been in the habit of painting his entire body blue with woad, dressing as a Pictish warrior, slugging mead from a ram's horn and sleeping in canvas tents — all to bring a bit of nourishing mirth to the sedentary inmates of a society in which he was a perpetual visitor and outsider.

"Your great-great grandfather was a showman in Scotland — a circus-man of Scottish Traveller descent." His son had come to America to be an itinerant goat-herder in Utah, and insofar as anyone on my paternal side could tell, itinerance stretched back in the family lineage until the dawn of time with only a handful of known exceptions. The few men of the Highland Mackintyre clan in the New World who'd forgone the vagabond's life in some form or other were roundly plagued by a grave dysfunctionality that ended them all. When I asked if there was anything that my father thought I should know above all, he only said that I should know that I'm a Scot, authorized to wear the Tartan of Mackintyre — and intoned that the ancient imperative of wandering place-to-place was probably my inescapable mantle.

I couldn't disagree. That I and he had been rambling across the roads of North America at the same time wholly independent of any knowledge of the other seemed a marvel to me. I hadn't a clue about any of this peripatetic predilection in my family tree — insofar as I could tell, my penchant for travel was an anomaly, for the other side of my family seemed to consist of hobbit-like stay-at-homes who relished the rectitude and peace of the settled life. Without a doubt, some blood memory was alive in me — an ancient connection to the insular tribes of wandering Scotsmen some derisively refer to as "tinkers," however tenuous or mythological. This blood was the same blood that always boiled up under my skin when I'd stayed somewhere for too long, causing me to "itch" and eye my maps and camping gear with a lustful eye. I found a profound comfort in these revelations, and as I near the age of thirty — that age at which a man is implored to start "settling down" — I am only emboldened that the nomadic ways of life my ancestors knew will continue to be a defining feature of my life until I am simply too old and broken to ramble anymore. My woman is of a similar disposition, having been raised in a band of Gypsy-like wanderers herself, and we've resolved to find ways to travel no matter how large our family becomes — lest the "itch" which sedentary life imparts on a born Traveller should wither the both of us.

Yet we do so without the royal blessing of the geographers of yore. In the settled world, there is no place for us but as temporary observers, poets, bards, healers, and showmen. I am sure that there are many more like us in the New World — perhaps the trope of the "drunken Irishman" and the "lugubrious Celt" are really tell-tale indications that many souls of the Celtic diaspora are unwitting descendants of the Travellers of the Isles; that their apparent status as eternally misfitten and lost souls owes only to the fact that sedentary life is unnatural to them. Born to travel — yet ignorant of their precise origins — they live a workaday life to which they are not well suited and it drives them to drink. My own relationship to spirits is, after all, inversely correlated with miles walked. I take no interest in drink if I am walking daily — without looping or turning around, breaking camp nightly as I go, placidly ensconced in the rhythms of my footfalls as I go.

While I might've secured tenure as a great geographer or map-maker in former days, to live this sort of life today, I must accept my status as a permanent stranger, vagabond, and — one hopes — a poet bringing nourishing mirth to the settled. Perhaps I am even a piper playing a homecoming song to lost Traveller relations in the New World — perhaps it is only a matter of time before the scattered embers of a culture so distant and unknown that it is only a sleepy-eyed myth or blood memory are rekindled and awakened. Perhaps there is a certain sense of inevitability and fate written into the metaphysics of human lineage — I reckon this is the greatest hope I could have in my life. As I survey the dozens of maps pinned to my wall, I wonder whether I shall find the others.

You’ve hit a lot of themes that have been bubbling up for me lately. I think there are so many people for whom the root cause of their malaise is ‘nowhere left to explore’. I’ll bet there was a time when it was comforting to know that someone’s out there doing the exploring, even if you weren’t doing it yourself.

Love that this gypsy found that nomad!!