Human memory is a damned feeble thing. For all that might’ve been gained a mere three generations ago in wisdom and in grit, and in toleration for incredible risk and hardship — it is all a passing vapor when pressed against the bright, flashing fripperies of our beloved modern times. The days of balancing a few haypennies against the pressures of larder, fireplace, shingle, saddle, and enterprise — their memory seems to have vanished in direct proportion to the difficulty they posed to our own forerunners.

And in eras when men weighed notions as grave and radical as “the Kansas question,” or “this matter about a little land up in Oregon Territory,” a different sort of man was bred. Such men seem to have rapidly met a speedy and unceremonious extinction, and lately, we are wanting for them again rather badly.

It appears to be the case that the precious march of progress will, if taken to its most extreme conclusions (as we have done in America) — subsume all memory of the bad old days in practically no time at all. For, ridiculous as it may sound, there are now men my age who could not tolerate one one-hundreth of the wild and hellish life of sacrifice and risk their own great-great-great-grandfather was likely to have lived.

These are the sorts of men who have a great many princely requirements; the sorts of men who shudder at the notion of a night without the pleasant hum of the air conditioner, or at the thought of a freezer bereft of microwavable chicken strips for even a few days’ time. Like sickly thoroughbreds suffering from their own pointless, inbred beauty — such men languish in a peevish state, toothless against whatever indignities may fly into their delicate faces. Their weaknesses cannot be genetic, for they are the inheritors of the genes that settled the Western interior and harshest Appalachia and the fierce-wintered northern Plains; it is true to say that they’ve been bred from good stock. If they are cursed by God, it is only by way of aimless luxury — and if it is culture that is wanting, well, they are only wanting for exactly what was ever thrown away on the grand and feverish sprint toward our Brave New modern World.

If such words as these read to you as harsh, my friends, well — they simply ain’t. For what we are dealing with here is a plain and simple old case of a thing known to befoul every great civilization and all great bloodlines — we are dealing with what can only rightly be referred to as degeneracy.

By this I mean no great sleight against my own peers, not in any fightin’ kind of way, anyway. For I cannot claim to have escaped this most malevolent force, either. I rather like glass-paned windows and havarti cheese; and I tend to get rather sour if I find myself lacking a good pair of machine-made leather boots. A sharp axe, or better still, a thermostat; a plastic bug-net to keep the high-June hordes of blackflies at bay — a little glowing box on which to type the words that’ll be sent out in laser-light form, down through a global mesh of undersea glass tubes, to the good people who’ll pay me to keep writing — why, I like all this stuff. I’d rather not live without it, too. And for it, I’m just as afflicted as any other man is today, in my own way.

In truth, I neither hunt nor gather nor farm — and yet I eat. And so it is that I am no better than those who I’ve now made it my task to critique. But as I read through the old tomes that deal with the history of the North American continent and its European settlement, I cannot help but hear a sort of murmuring ghost who lives between the pages of such books, whispering to me about what I myself have lost. It seems that we have all lost it — and that this loss, tragic as it has been, has not received one-tenth of the funeral (or resuscitation) it really does deserve. By the by, it seems to mostly go unmentioned, except in the vaguest sort of platitudes.

Instead, the loss of the old rough-and-tumble gumption of our forebears has not entirely been eulogized or buried — but neither has it been given space to breathe and recover, either. Instead, this most potent spirit of the “North American Man” (and by that I do include Canadians and Mexicans here, in addition to us Americans) has only slithered about in the ether, yearning through the frustrated subconscious minds of so many modern men who reside now in the land conquered and constructed by our progenitors. It has lived as a zombified thing, or as a virus in the deepest realms of the brain’s bowels — it’s a thing that governs and moves us and spurs us to take action, but the action it has lately produced is only perverted, deflected, and pointed back inward in a kind of psychic seppuku that now ravages the culture of the North American continent.

If, in all I’m yammering on about here, you find yourself wondering just what the hell I’m talking about, consider this:

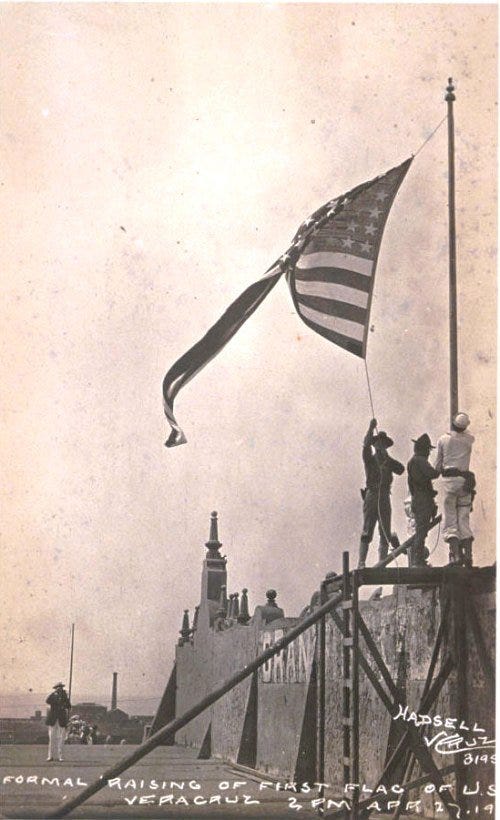

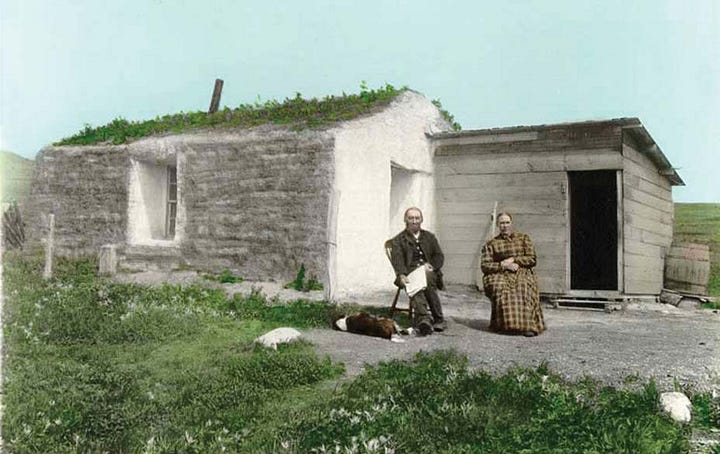

In 1620, 1720, 1820, and indeed, even 1920 — ours was a landscape that gave no quarter to whining. Salvific forces that could scoop a man up out of his desperation and lead him to paradise were limited solely to the metaphysical realm of life. This was the purview, more of less completely, of Almighty God and none other. There was no “bail out” for the French & Indian War era settler along the northern frontier — there was no WIC for the Nebraska sodbuster nor a Social Security program for the vaqueros deep in Bolson de Mapimi.

And if a man should find himself meditating upon a “housing crisis” at any point in any one of these centuries, why, the solution of such a crisis was wholly incumbent upon him to find, engineer, or seize. It motivated him to build a house, and to find site for his dwelling come high or hell water. If he failed in this, his only recourse was to learn to enjoy the taste of rain and the nightmarish feeling of frostbite on his digits.

These days, the life of our people is a hell of a lot more comfortable. And if I could be so bold as to make a direct comment about what the wages of this comfort have been — I’d say it’s killing us all in a hundred ways. For where in America can you go now without finding bored, frustrated men who simultaneously yearn for a frontier yet also lack the gumption to go out and find one? And what do such men do but flounder and fornicate, take to liquor or to pot or even to ‘fent,’ or languish on all-too-safe paths that kill the soul and spur a weakling fellow to inch ever-closer to the noose? Or — they find crime, or war, and fizzle out into a fever. Gone are the days of a man exercising every pound of his flesh against the elements; of scooting out like a mad dog in deep prairies or cold islands or stomach-churning seas to build and create and eventually steward his hard-fought prizewinnings.

No longer does a man run himself haggard as he fights to build what he can out in some lonesome and dreadful land of opportunity. Now, the only “frontier” is the cyclical existential angst he does battle with alone, in the depths of his own soft-bellied interior. I am no stranger to this myself, and I suspect most of us under 35 years of age aren’t either.

Along the way, he might get an inkling to look toward whatever high-held structure approaches a place of true power — and beg for it to see him, to know his plight, and to ladle good fortune out onto him as its own loyal son. But where once such a thing as this was strictly a matter of prayer — now it seems to have become a matter of politics.

“Housing is a human right!” goes the chant of our leftist agitators in our cities. Such “rights” as these are, perhaps, not exactly the rugged old rights that ever hearkened from a place of divinity and naturalness so much as they are rights conferred upon citizens by an extensive and all-powerful secular state. For this slogan is no prayer — it is a demand, and at that, a demand upon the state to intervene in a decidedly particular way. For some, it might mean the construction of more public housing, or the implementation of more rent control and rent voucher programs. For others, it could be a “YIMBY” type of sentiment, that developers ought to have the green-light to go ahead and keep on building ever upward in our biggest cities. In truth, this slogan carries a great deal of weight from a diverse number of sources and sentiments — but at the bottom of each is essentially a request to the almighty government to ameliorate a crisis against which all victims are otherwise helpless. Nevermind that in many cases, it was the government who facilitated or even created the problem in the first place (see: Building Codes and Zoning).

Then again, if I’ve picked on “leftist agitators” here — it is only to credit them for having such a keen understanding of the times we’re living in. For, as far as I can tell, and after many years of deep, earnest study of leftism — it seems to me that we’re all leftists now. For what is the spirit of leftism if not one of making demands of the earth’s secular powers — or of seizing them in order to create a technological path to universal and equitable technological comfort?

I say this only to highlight the simple truth that the old, conventional, historical political divisions ever known through the history of Western Civilization have, by now, all been simmered on the same pot over the same flame. Modernity, the techno-industrial civilization, and the psychologically debilitating degree of comfort that we have now achieved have taken us all well past politics in their classical sense. The chief differences between “right” and “left” are now almost solely aesthetical in nature — in substance, they both take the form of cries raised in the direction of the state’s giant bureacracy, to intervene for the citizen, that he may be delivered from his every grievance by way of central banking, high finance, and higher technology. And at the end of it all, ideally, a suitably Instagrammable result will be produced in the lives of all the citizenry who supported the effort.

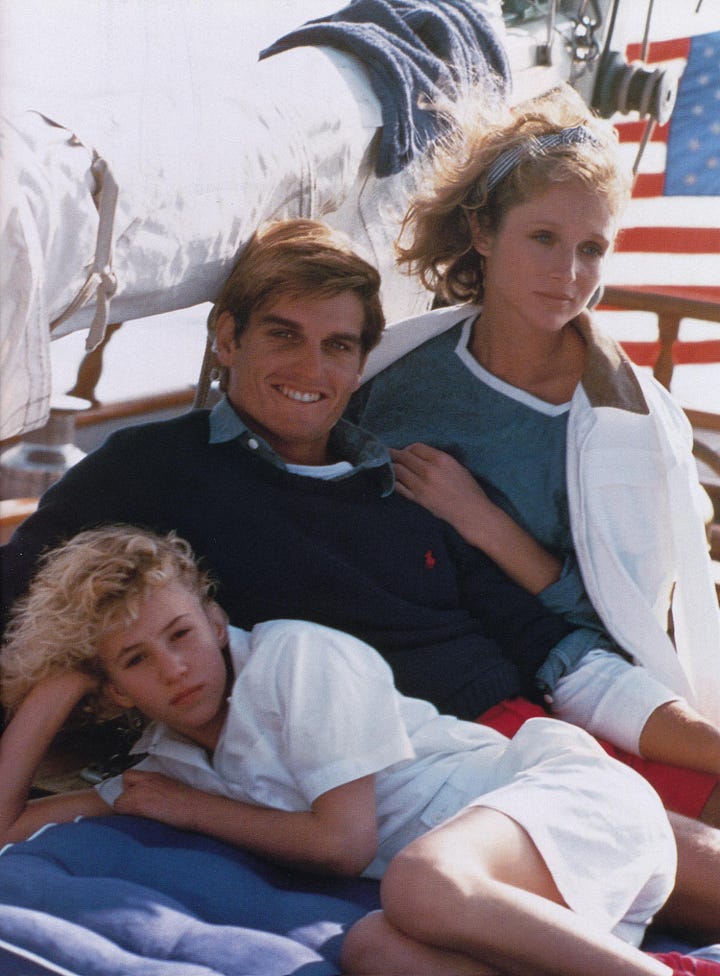

What is actually argued in the public sphere today, then, is what that ‘techno-deliverance’ will look like in aesthetic terms. The “right-wing” fellow might want a state-mandated recreation of 1980’s Ralph Lauren magazine advertisements for him and all his buddies the country over. And his “left-wing” counterpart wants all the same A/C, the same building-code-compliant drywall, and the same plastic-wrapped grocery sweets as his conservative neighbor does — he just wants the whole mess of it to look more like a queered-up “Corporate Memphis” picture and less like 80’s-era Ralph Lauren. They both agree on the big stuff — “economic development,” “human resources,” electricity, flourescent-lit grocery stores, air conditioning, WiFi, government subsidies for industrial infrastructure, you name it. These agreements are so sweeping and so totalizing that the actual disagreements between left and right now, often enough, seem only like window-dressing at day’s end.

What these agreements seem to belie, above all, is a sort of universalized drainage and death of old-time American gumption. That old, “get-your-ass-in-gear,” tearin’ across the prairie, kissing mother goodbye and taking a train out to the territory, cut-your-own-shingles and deliver-the-twins-in-the-sodhouse type mentality — both “sides” seem to agree that that type of thing is altogether best left in a museum, or in a history book that neither of them actually cares to read. On the off chance either of them did walk that museum, or read that book — they’d now be liable to be offended at what these histories might seem to imply for their own lives.

An irony comes to the surface in considering these things: The very grievances at the center of an individual’s politics would, most often, be able to be solved if only they’d shake off the stupor induced by their beloved modern comforts, read a little of the history of our country and of the human race at large — and then saddle up to take a heavy dose of gumption. For gumption seems to have a way of producing action — a thing that any earnestly political soul is almost by definition allergic to.

On the topic of housing — which remains a sort of locus point of collective anguish among the youth of all political stripes — a simple thought experiment regarding gumption bears out clear results. This is a hornet’s nest I’ve been known to poke a great deal over on X, and to me, it’s a nest that is quite worth poking. Here’s what I said way back in April 2023:

In Lansford, ND, you can buy this house for $15k. It's a little rough but livable. In the same town, Northern Plains Railroad is hiring for $25-28/hr for a Utility Mech. No experience required.

There's no 'housing shortage' -- there's a shortage of imagination and flexibility.

The responses provoked nothing short of opprobrium and feverish belches of rage. Many users decried the idea, citing North Dakota’s freezing temperatures, the sheer distance from momma’s house, the incredible boredom of life on the Great Plains, the (wholly imagined) dearth of suitable romantic partners in North Dakota, or the apparently “uninhabitable” state of the house (which is to say, the modicum of effort it might take to install a stretch of flooring).

In reading all of these, I quite wondered what all of their great-great-grandfathers would think about such a precious display. No doubt, whatever they might say about all this would be dismissed with utterances of “OK, Boomer” and scorching indignation. And where it might be tempting to imagine that it was only the urban leftists who raised such cries as these — I can assure you that the white-collar, status-seeking, suburban-type right-wingers were every bit as indignant.

Yet none who commented seemed to be able to disprove the very real possibility that their tears over “the housing crisis” are, at the very bottom of it — vainly shed. For unless the sacrifice of our forefathers purchased for us some kind of Divine right to an extremely novel form of housing in a top-ten metro area, it would be reasonable to assume that we all would be capable of accepting a far, far easier, safer, cleaner, more comfortable iteration of what so many of our own forefathers went out and did. That little house in Lansford wasn’t a sodhouse, and it wasn’t surrounded by marauding bands of Indians who might seek a householder’s scalp. The grocery store down in Minot is dutifully stocked with historically unimaginable luxuries (like coffee, pineapple, and blueberries in January), all on the cheap.

And as for talking to old momma back wherever she lives, well — at least you’d have telephones, Zoom, interstate highways, and commercial aviation. Lord knows the first settlers in North Dakota had none of this; yet they built an empire of sugar beets, wheat, cattle, and oil there nonetheless.

Why, then, would this proposed solution to a “housing crisis” provoke such an intensely emotional response? Perhaps that’d be because the life on Easy Street that we’ve all enjoyed since we were in diapers is a life to which we are all emotionally attached. And as with any emotional attachment, an otherwise reasonable and lucid human being can be provoked to irrational bouts of outrage when presented with any notion of being separated from that to which they are attached. This is what they call a psychologically pre-operational process — and it seems so far to have succeeded in producing generations of Americans who have an iron-clad immunity against the old-school, original gumption that built our very societies.

So far as I can tell, the only way to shake this attachment is by prolonged separation — as one finds it in militaries, homelessness, extended wilderness camping, seafaring, or life in third-world countries.

Indeed, it was that gumption that ever built our world of luxuries in the first place. Yet those to whom it is an alien thing seem not to taste so much as a whiff of irony on these points. It is fair to wonder where these internal contradictions will leave us in the end.

More frightening still, perhaps, is that the litany of smaller ways in which gumption is necessary for a robust and worthwhile human life are also shapeshifting into a weaker and whinier form. Where once a fellow had to go out on a limb to ask a woman out — and felt lucky to get a date with practically any decent woman he could find — now, the subject of dating is a damnably sore one for so many “blackpilled” American men.

And I stirred them up, too, in quite the same fashion as I stirred up the “housing shortage” crowd with my post about North Dakota. Last June on X, I wrote:

Here's my advice to single American men who feel hopeless about ever finding a good woman to marry:

Take a month or two between jobs and drive across the USA. Stop at every gas station and truck stop, and eat every meal at diners during non-rush hours. Avoid cities; stop primarily in poor rural areas out in the middle of nowhere.

Every time you see a pretty cashier or waitress with a good vibe, politely ask her out. Tell her you're out seeing the country and looking for a place to settle and a good woman to marry. Repeat until you've found someone to go steady with.

This worked for at least one young, awkward guy I knew at a Catholic Church in Louisiana. Met his wife at Love's on I-80 in Iowa. She converted, moved to Louisiana with him, and they go back to Iowa together every Christmas, fueling up at the truck stop where they met.

She was giddy to find him, as most of the men in her town were either already married or total losers. They were both in their early 30's when they met. I had planned on doing this when I got out of the military, but Providence had it that I'd never have to try it out -- I'd be engaged to Keturah just before my discharge. But I say to any young man having trouble finding a woman it's absolutely worth a try.

At worst, you see the country and go on a few bad dates. At best, you find the love of your life.

Again, as with the North Dakota post, this Tweet drove the internet utterly wild. The post received 14.3 million views, and was even read (and endorsed) by Matt Walsh on his show. Thousands of people found my formulation disgusting, or creepy, or “serial-killer-esque,” — and thousands more found it to bespeak a very necessary and quintessentially American flavor of gumption and grit. Many of the more progressive commentators chided me for “encouraging sexual assault in the workplace,” and many of the conservative types seemed to think that the types of women working at gas stations and truck stops are all “toothless, obese, and on meth.” In all, I could only marvel at the sheer diversity of the delirious responses to what seemed at the outset like a simple, wholesome, adventurous little idea.

In either case — many people from all sides of the political spectrum seemed to condemn my advice. And by the same token, many of these same people were also the sorts who are “blackpilled” on dating, or are those known colloquially online as “incels.” Practically everything they said on the matter seemed to boil down to a professed emotional attachment to their lack of dating prospects — and they responded with an inferno of outraged disbelief at the idea that they could change it.

None of this was my goal. In general, I have taken keen note of the respects in which young people seem to be anguished and suffering — and I have noted again and again that a great deal of this suffering is chosen, and at that, chosen on a voluntary basis. To kick things into high gear, take a little risk, and stray away from the “Instagrammable” vision of what life ought to look like — that has always struck me as the cure for most peoples’ angsty yearning. It’s certainly been an apt cure for mine. And yet it is precisely these sorts of actionable, here-and-now, bold rolls of the dice that seem to make those same suffering people so completely mad and outraged.

At the risk of offending any of my readers who might profess to hate Donald J. Trump — I can’t say that I am particularly against the idea of Making America Great Again. I forcefully reject and scorn the likes of those, such as former NYS Governor Andrew Cuomo, who claim that “America was never great,” as he did in 2019. And I can’t quite accept any idea that “America was always great and still is” — or any idea that the “again” in “MAGA” is somehow unnecessary. Being from the decaying ruins of Upstate New York, where grandeur has not only faded but has actually completely rotted — I can accept that we’ve had some kind of a fall from grace, and that in turn, it’s time to get back up again in a very real way.

Whether President Trump’s actual movements in this direction will bear that fruit or not is another question for another article. But suffice it to say here that if I have any real criticism of the “MAGA” idea — is it only this: We cannot Make America Great Again without gumption. And our citizenry (particularly the younger folks) seems to actively detest and revile anything even vaguely approaching such a thing.

I hypothesize that this open, bald-faced hatred of or aversion to gumption is not merely an arbitrary change of culture, but that it is a spiritual malady that has been caused directly by the suite of modern technological comforts that have accompanied our blind march into “progress.” It has also been caused by deracination from the land and from the God who has made this most well-appointed, rugged, and possibility-laden land — and indeed, our world of modern comforts has wrested us all off the land at harrowing speeds.

In all truth, the material and technological basis of our culture has moved at such a rapid pace that no man can keep his eyeball on it as it goes. We can’t keep track of it. So many deep-reaching changes have occurred in so short a time that I reckon we’re all in a collective state of shell-shock — and that this en masse flavor of shock is only a continuation of a thing that began at the close of World War II. Ripped from the land, packed into a world of blinking, beeping novelties and empty bureaucracy, ushered into an arena of both Godlessness and endless digital imagery that always depicts a mirage of a lifestyle we can never obtain — the great mass of us find ourselves clinging onto what little security we can obtain in our various comforts. In so doing, we cling to the very thing that ever caused America’s temporary fall from grace in the first place. And indeed, it is that very thing that now looms as the only thing actually capable of killing this country and ending the long, strange story of America once and for all.

For we are hard to invade, we are laden with incredible blessings in the way of good soil, timber, ore, and oil. We could be cut off from the rest of the earth entirely and continue to eat well and build world wonders. There’s power in things such as these — but when one has constructed the greatest fortress in the world, one finds its weakest point is found in the psyches of its occupants. What good is great sculpture if the sculptor is a madman who pushes his greatest works off a cliff in a bout of insanity? What good is a fertile, beautiful continent packed with descendants of history’s most capable soldiers — if they all lose their wits and their resolve, if they suddenly have no tolerance for risk or discomfort, and languish in suspended motion, high among their piles of luxuries?

And so it is that I find myself arguing this: If we are to Make America Great Again (with or without Trump) there will be no choice but to address the Great American Gumption Shortage. Without uncovering the old embers of former days that still do reside in the blood of our countrymen, and setting them aflame again — there is no “MAGA.” There is only air-conditioned anomie and dread; only excuses and aimless demands in the political arena — only an ever-changing matrix of aesthetical cravings and fashions that shall not fill the void where great adventure, risk, and great feats once stood tall and proud.

In closing, perhaps it would do some good here to remark upon the specifics of what this gumption could look like, or where it could go. It is now a popular idea to imagine that “there is no frontier left” and so on — but I find such ideas to be baseless and melodramatic, and I would like to explain why I would think such a thing.

From the first, it’s worth saying that there are a litany of ways in which Americans used to act as they approached life’s problems, big and small — and many of these methods deserve to be brought into good use again. At the very start, I must highlight one — a staunch refusal to complain about one’s plight. Rather than languishing in disgruntlement, or hoping for some external force to liberate us from our trials — it is of critical importance to instead focus on immediately actionable solutions to all of life’s problems. If none exist within one’s comfort zone, well, the problem at that point is usually not the world or the cruel forces that seem to have built a wall between a man and his dreams — it is his comfort zone that is the problem. Widen the aperture of how we approach our problems, I say; let us head off into experimental territory as we seek each particular end in life.

Had none of our ancestors ever given this method a try, Arizona would be an empty wasteland — and indeed, North America would be a vast wilderness. Virtually nothing we now know, think, or use would’ve been uncovered.

For by all I have gathered in years of extensive study of our frontiersmen and pioneer forebears — they simply began at the beginning, with no thought paid for what should be. A means by which to keep the rain off of one’s head, and to keep the heat of some kind of stove inside one’s domicile — that was the baseline in housing. A few bowls of cabbage, or a few loaves of bread; a little beef now and again if you can swing it — such would suffice for one’s subsistence in a pinch. Porter and prime rib, crown molding and gilded doorknobs, running water and telephones — these were filed under “someday” if circumstances demanded. What one did until that someday came usually involved either a great deal of work, or a fair bit of scheming, or moving overland to wherever land was cheap, or a combination of all three. It’s a time-tested way to conceive of home economics, and so far as I can tell, there’s nothing wrong with it.

To interrupt this most natural and ancient process of discerning our needs with an impudent cry of “but I deserve…!” is a fool’s errand. To weigh and carry each of one’s basic needs with realism and gratitude is an honorable thing. When “boomers” complain of “entitlement,” I do understand what they are complaining about — if only because it is painful to watch suffering people further hobble themselves with so much mishmash about what they believe they deserve; all of it preventing them from doing anything.

For still, even to this day, there are opportunities that could be considered analagous to those found by the early pioneers — and a fair few of them still exist within the legal boundaries of this nation. Towns in Kansas that offer newcomers free land; uninhabited islands in the Northern Marianas, Alaskan bush parcels where no property tax of any kind is now or ever will be collected. But more to the point — there are frankly even better opportunities than these in America; opportunities that most of our pioneer forerunners might’ve chosen well before they went for the ‘hard fifty’ out in the Western desolation.

Tens of thousands of potentially-habitable properties now exist throughout the country at rates well below $50,000 — some of these are even under $10,000. These could range from half-acre lots in counties with no building codes or permits, where a man could build himself a cabin from whatever scraps he could locate — or in much-maligned and economically depressed backwaters in Southern Illinois, North Dakota, Upstate New York, Rural Arkansas, or Pennsylvania, one may be able to find a ready-made, move-in-ready home for well under $50,000.

In many cases, you couldn’t build these houses for what they’re charging for them — and in that regard, you are in some sense getting paid to buy such a house. That is certainly true of my own house, which I purchased about two months ago.

Our 1,100 square-foot, two-story, three-bedroom home in the Adirondack Mountains cost us $33,000 cash. It’s got a 1,000 square-foot barn, a brand-new propane furnace, a wood-stove, and two giant porches, all nestled in on a tenth-of-an-acre village lot in a 250-person village in the wilderness. Our town has a daily bus line to the County Seat for groceries, and it’s got a gas station, liquor store, bar, library, Catholic Church, school, and 76,000 acres of forever-wild wilderness preserve within walking distance, including several islands and waterfalls. Our monthly taxes, sewer, and water bills altogether total $115 per month. We own it outright, with no bank, no interest, no nothing — it’s ours, for a monthly price that’s about on par with a single night in a Motel Six. And beyond any reasonable doubt — we could not have built this place for $33,000.

The home’s only real blemish is found in three or four beams that must be replaced in the floor — but the job is not that serious. We moved right in, and I am typing this from this house, with a view of the mountains in the distance. In the summer, we’ll sister a few new beams in in the crawlspace and the job will be done — good as new, if not better.

You can do this too, if you wish. And while many talking heads on the internet might lambast our town as a “shithole” and our house as “uninhabitable,” well — we suspect that by Pioneer standards, we’re living downright large. Such things as what we have done are still possible in America, if only people will buckle up and go for them. And for all the talk about a “housing crisis” I now see, well, last time I checked Zillow, there were still some 11,000 homes for sale in America for under $50,000. Until I see more of those getting bought up by the folks who’re hot around the collar about housing, I’ve just got to assume that this “crisis” business is all talk.

The only trouble with a course of action such as this is that we’re pretty much alone. In resettling the heartland of America, and in thereby “Making it Great Again,” as I like to think we are now doing — we just don’t find very many newcomers with the same idea. Instead, we find “MAGA” folks lampooning us online — literally making fun of us for actually going out and fixing up this country’s bones, and for salvaging some of what our ancestors built when they settled this country. And meanwhile, more than a few of our “MAGA” neighbors rather wish that their beloved hometowns wouldn’t just dry up and die.

I can’t make it make sense, myself — but I can celebrate American gumption, and I will exhort all who care to read my own meditations on the matter of America to hop into their granddaddy’s saddle and GO! Get on it, my friends! By no means can the best of what the country is and ever was be propped up by any political establishment, no matter whether they’re renegades or not. There isn’t any kind of Executive Order that can replace that certain gutsiness that makes an American an American. No Act of Congress can get an aimless young fellow out of bed to get him to swashbuckle his way to a Lousiana shrimp boat, or to convince a “blackpilled” online “shitposter” to put the phone down and go buy an old hardware store in small-town Nevada.

If all this sounds real romantic — that’s because it is, and at that, it’s unapologetically romantic. The modern, air-conditioned, chicken-tender-fed American seems to want a bureaucracy of rational, clear-cut life choices laid out before him, all like silver finery on display.

Well, that’s not what our great-great-great grandparents got — instead, they simply got wild ideas, hit the road, tore up the stakes, and made it happen. That was what made them Americans. Every one of us can do the same, and the sooner we adopt that kind of hell-yeah, get-up-and-go, make-it-happen mentality — the sooner we’ll actually “Make America Great Again.”

So hit the road. Hop a freight train. Buy the old house in small-town Iowa. Ask the waitress at Denny’s on I-90 out on a date. Build a boat to live on in the swamps down in Mississippi. Take the fishing job in Maine. Run for Mayor. Think on what sort of life your great-great-great grandfather lived, and what sort of modus he employed — and adopt it as your own. It’s quite likely the very best part of your inheritance as an American.

Please take these great essays and make a wonderful book with them! (I’ll beg.)

There is nothing about this I don't love. I have been thinking for decades that we are hopefully heading for a time, given the ability to work remotely, and people just getting sick of all the trappings that are now considered necessary .... where more people will just head for these nooks and crannies and live their best lives! Thank you for writing about this so eloquently.