Lately, I seem to get a tremendous number of requests for advice from various readers. I consider this to be real strange, as I was never in the habit of taking any of the advice I’ve been given at all; and so naturally, the idea of giving and receiving advice is at least a little foreign to me. In fact, in all truth, I’ve made a sort of career out of doing just about the most inadvisable things a fellow could do. Godlessness, indefinite unemployment, Communism, drunken trysts with wild wenches, hopping freight trains, dumpster diving — hell, I even ate a half-rotted roadkill fox once, against all warnings, and paid dearly for the experiment. Indeed, I am almost the king of doing foolish things that most lucid individuals would quite rightly tell you never to do.

But perhaps the startling amount of solicitations for advice that I receive annually is a sort of ‘canary in the coalmine,’ or a sign of the times. You know you’re living in strange times when you find yourself emailing a literal hobo in search of wisdom. Nevertheless, these are, apparently, indeed the times we’re living in, and one friend of mine reached out to me for exactly this reason. Her eighteen-year-old son lives in Georgia, and has lately been feeling a little “stuck.” She wondered if perhaps I’d have a word of advice for him, and so I agreed to write him a letter.

Though this letter is tailored to him in particular, I suspected that others might find it a worthy read, and so I’ve published it here as an open letter, with permission. Perhaps you or someone you know would find it to be of interest. Thanks for reading, and without further ado — a letter to a young man in Georgia:

Dear Friend,

On the day you were born you hadn’t the slightest clue where you were or what year it was. You could not have known a thing about any of that — though if you could’ve, it might have been fair of you to presume that you could expect a life in the bush, as a hunter-gatherer.

For in the great, long, blustering story of the human race, the vast majority of our centuries have not been civilized times. They have been times well before the dawn of agriculture and cities, before alarm clocks and chicken patties and Instagram and all of that. Times when an infant boy could’ve reasonably expected to live a life of sleeping in rude huts in the wildlands, driving antelope down steep gullies and gutting them with knives made of flint or chert. Berries and mashed roots, naked swims in the waterfalls — grisly, feverish, howling, spasmodic warfare against neighboring tribes; there was a very good chance that this could’ve been your lot, as it was rather normal across the history of the human race.

Indeed, whether you realize this now or not, you were made by God and by nature to do more or less exactly that. To live a primitive, strenuous, wild sort of a life — a life of rough imprecision and corporeal risk, and at that, a life lived alongside the auspicious principalities and powers of barbarous wilderness; this is what you were built to do. To trek out onto vast and desolate wastes, bearing a spear rudely crafted from parched brakes out on some devilish bog; to seize upon woman as the peregrine ravages the salmon, to live as a foreigner to written words but not to bloodshed nor the gleaming viscera of game — a young stripling buck of the priordial chaos from which the human race sprang.

Even in reading such words as these, does your heart not leap a little at the notion?

Alas, I regret to inform you that you missed the boat on all of this, and as a baby, you did not have even the slightest inkling of what a profoundly different time and place you would be born in. For instead, far from the world of roasted moose entrails and wooden arrows and songs sung under ancient oaks by moonlight — you would find yourself in modern-day America, and I am here to tell you that such a fate is, so far as I can tell, a mixed blessing indeed.

This topic is among the few on which I can rightly speak with any authority; for I was born here too, at more or less the same time as you were, and in more or less the same place. Though I am twelve years your senior, and am an Upstate New York man rather than a native son of your Keystone state, I am intimately familiar with life as a modern-day American.

Oftentimes, I have quite wished that I was not. For I must state quite emphatically — this ‘modern way of life’ thing is not for me. It never was. All my life, my flesh has revolted against the thing, for it is so incredibly grim and unnatural. At the same time, no, I am not tempted to imagine barbarian times as being some kind of an Eden, not really — I know well enough what incredible exertions such times required of men, and of the heinous tragedy such a life often involved. I am often grateful to have been spared all this, and in so saying, I tell on myself as a thoroughly ‘modern’ sort of fellow. Nevertheless, I have often suffered from a keen sense that I am out of place — for I have a hard time paying attention to the time, or to my taxes, or to calendars and jobs and washing machines and other novelties and trivialities. The limpness of the body such times as ours can inculcate stifles me; the paralyzing safety and the hubristic certainty of everything is altogether suffocating to me, even now.

This is, I suspect, why I wound up living life as a hobo for a long time. I hated the pallid hues of the workmens’ faces; I resented the very concept of “money.” I wished to go out for blood — to set the hairs about the back of my neck upright, standing perfectly straight as pins, tasting death in great big horrifying draws as if it were icy water from an opaline well. With skis strapped to my feet I flew from great heights, dropping down cliffs on thickly-treed mountainsides like a madman — sucking down whiskey and canoeing down hellish and somersaulting rapids as if I had a death wish. Later, I did the same as a hitchhiker; riding with meth-heads and drunks and perverts. And verily, I did have a death wish — I had the very, profoundly, completely normal urge that all young men must have in our times; to slither out from under the weight of my own flesh to become a sort of wandering entity, without body or bone; a creature composed purely of myth, forever unhampered by the inconvenient and often ugly realities of my flabby mammalian form.

Contemplating such things at the age of eighteen — I often said inwardly, as I believe you yourself have: “sometimes I want to get up in the night and just start walking.”

This was not, perhaps, because I anticipated anything particularly heroic out in the wide world I’d be walking in — but it was a sort of incantation mouthed out of a desire to move myself, to purify my flesh by way of exertion; to give my boundless energies some kind of an outlet, however insufficient it might prove to be. Whatever my lot in life had been, whatever tasks to which I’d been assigned by way of my birth — I aimed to slough them off as a stubborn equine bucks off a load strapped to his back. And I succeeded grandly at exactly that. As a matter of fact, even now — with a little help from Uncle Sam, my beautiful wife, a few hundred online benefactors, and God almighty — I still have never picked that load back up, and as a result, I quite blessedly remain an almost totally feral sort of man.

But to get from infancy to where I now sit — without going mad and without losing that ‘wildness’ that sits at the heart of any decent man — that is the central question. Sufficiently addressing that question is exactly why I am writing to you now. For though we have never met, and though we are (unfortunately) separated from easily doing so by way of 1,100 miles of American soil, it came to my attention that you might be in a fairly similar position to the one that I was in when I was your age.

The reason I ever learned of this was because your mother told me; and do not be embarassed over this for even a second, for it is all very natural and quite a normal part of one’s ascension to manhood. Eras like our own are, if we are to take a 10,000-foot view of human history — aberrant times, or extenuating circumstances; quite akin to a hypotheitcal time during which eagle chicks are all hatched inside of a Wal-Mart, and are consequently prevented from fulfilling their natural purpose. Men born for swashbuckling frontiers, oceanic voyages, beaver trapping in the deep Northwoods, great battles with enemy nations, and famous last stands atop high mountainsides — men like these are now born into a world where such flourishes of mythopoeic romance are exceedingly hard to come by. These days, they are often enough absent unless you have a sturdy imagination and a frightful and insistent degree of tenacity.

Because of this sad shortage of myth and wonder and frontier, your mother found you making intonations about “getting up in the night [to] just start walking,” “hitchhiking across the country,” and “living out of your car.” All quite reasonable instincts given the circumstances, I’d say — and all markedly more doable than you’d probably imagine. I can, again, speak with some authority on these fronts, as I’ve done all of them to such an extent that I am, in some circles, considered the vagabond par excellence — a veritable ‘king of the hobos,’ or at the very least, one with royal blood among vagrants, dropouts, and wanderers. On matters like those, I have much to say, and perhaps this is why your mother asked if I, of all people, would offer you some kind of counsel.

Prior, of course, to offering you any insights about how to go about doing such things, it is wise to contemplate where it would all leave you in the end. For make no mistake — vagabonds have a way of dying early deaths, and of more generally finding themselves proximal to death somewhat regularly. I have watched people overdose on heroin, I have known many who died on freight trains or by their own hand, I have fought and even seriously wounded human beings and animals who’ve sought to attack, molest, or deprive me of my few belongings. What the vagabond can and will usually see will darken him, and I will say before you even consider living such a life that it is of paramount importance to bear some light within you. To know God, and, if I may presume to know anything of your faith here, to know Jesus Christ — this is one armament that I did not carry with me as I traveled, and for it, my soul was bruised far more seriously than it would’ve been otherwise. I urge you not to make the same mistake.

Alongside this weighty consideration — a purpose. For one thing has struck me more and more as I’ve aged, and it’s the importance of working backwards. By this I mean: set your heart upon some lofty goal (the loftier the better) and let it become your timeless and unshakeable maxim in life — let it buoy your every action in daily life, such that the setting of every sun finds, God willing, that you’ve inched at least one inch closer to your most venerable and sacred goal. But understand this: such goals as the type that could suffice toward this end are rare to come by, and it is quite likely (and quite normal) that you would not be in possession of it today. For this, you must go on a sort of ‘vision quest’ whereby you wrangle such a goal and bring it into your possession, as one ventures out to exotic quadrants of the map in order to procure a rare and valuable seed that will someday fill great valleys with its heavenly flower.

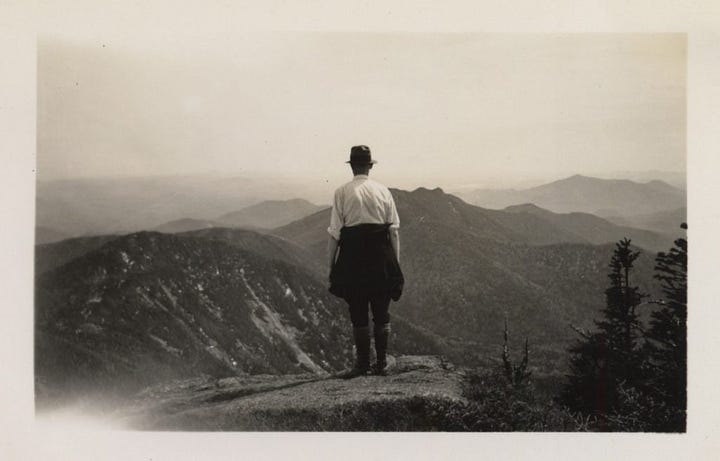

Now you may be seeing clearly what I am saying — if you have ever pined for a frontier, and have mourned the closure of the American West or the end of the mythic eras of men, well, you have mourned vainly. For the process I describe — the process of obtaining the goal that will gild your every hour — this is a frontier all your own. And lest you should get the sense that I am only making witty equivocations here, or are playing some kind of a parlor trick with rhetoric — understand that I mean this all in the most serious way I could mean it. If you find yourself in a rut, my friend, you must take action, and you must do so immediately, and physically. Do not research whatever it is that you choose to do; saunter up to it as men in battle saunter toward their quarry — stalk it as you live and breathe, as hunters do. Banish neuroticism, risk-aversion, and overwrought calculus of every kind. Lift up your musculature and bone (and indeed, your eyes) and move forward; understand that the story into which you are now stepping will appear to you only in vague, random strokes and visions — and that it is, above all, your task to navigate such strange and immeasurable phenomena deftly and with incredible style and grace.

For before you have even obtained the slightest whisper of a goal, it will be style that you will have to cultivate. A man with style can stand naked, penniless, imprisoned, alone — and can suddenly find himself ascending to startling heights with preposterous speed, and he will have done so solely by way of his immaculate and effortless style. And, on the obverse of this formulation; there are billionaires, CEO’s, statesmen, and Kings who, for their lack of style, will have for their legacy only the barest and most perfunctory footnotes and nothing more. Let this most important ember of wisdom (perhaps one of the only ones that I have managed to securely obtain) float upon the surface of your brain and heart — and let it be your task to seek to live it as truly as you can imagine.

And like many quests worthy of the term quest, you will scarcely know when you have succeeded at it or completed it. There will be a litheness to your muscle; a weightlessness to your bones. Your face will glow as if it were a small sun in and of itself; the eyes of others will be fixed upon you with solemnity and seriousness. Your back will be erect — and your stance will seem as if it is anchored by great leaden weights when you stand before anyone, be they friend or foe. More than this, you will find yourself remembered — even by those you yourself have no recollection of. There will be circles in which mere mention of your name will bring great broad grins, or, conversely — even fear. These will be the fruits of your long and ardent pursuit of style, but they will only come to you after many difficult miles.

But how to begin? This may well be the question that has now risen to your mind. On that matter, I am reticent to give prescriptions, as I do not know you well enough to say straightforwardly what would now be the best for you to consider doing. True enough — were you to pick up an Army surplus rucksack, a sleeping bag, a metal pot, a knife, and a copy of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, and to get yourself a Greyhound bus ticket to Yuma, why, I’d say you’d be on the right track. And then, to walk north, or east, day in and day out, carrying water and bread and dried meat and apples and a little coffee — yes, you’d probably find what you are looking for (so long as you took great care to stick with Christ Jesus, and to stay away from drugs, liquor, and slattern women).

But of course, such a dramatic course of action may not be desirable, or neccesary — perhaps your particular Odyssey would involve Law School, or the Marine Corps, or a fishing boat in Alaska. Perhaps it would involve acquiring a dirt-cheap house in Saint Mary’s PA, to read the Western Canon at the public library, to pick up playing Celtic jigs on the accordion, and to start an enterprise in breeding prize-winning pigeons and quail.

I cannot say what particular journey or goal is the best for you to pursue — no one can. Determining what to do is strictly your job, and I should offer a word to the wise there, to say that it is best for you never to ask others what to do, but instead, to ask them how to do it. If you are experiencing a shortage of ideas on what to do, which is really a common affliction even among men thrice your age, then I will give you a prescription for this: walk ten miles every single day, rain or shine. And spend the rest of your day at the library, reading an entire book every single day. In your reading, avoid stupid self-help books and any novel that could not be considered a classic; perhaps lean toward non-fiction about history, industry, war, and geography. Balance it with poetry, great American novels, botany and ecology. And stay on that regimen until you get a wild hare to try something, for no doubt, a strenuous course of self-directed study will produce it — and when that day comes, do not move slowly but leap toward whatever it is, so long as it is moral.

You must understand that you are from a country that was built by men of action. Sturdy souls who did not fret and frown and wonder at the risks; men whose minds were not clogged with so many words and expectations and apprehensions — but men who went and did it, whatever it was, and whether it was for good or for ill. It is lately popular among young American men to forego this most essential quality of who we are as a people, and to do nothing, to overthink, to be sucked down into a nervous, effeminate miasma. But I must implore you to heap disputations upon such sluggards, and to craft your proofs against their nail-biting theorems and warnings not with words but with actions; and not to do so for the sake of disproving them alone, but in hopes of sending them a clarion call to disabuse themselves of their lack of gumption. Rise to the occasion, decisively and with tremendous style and apblomb; wear the full weight of your life’s many miles and myths on your flesh — build something that glistens in the eyes of even the most cantankerous critics. Hurry to do so, but do not, in hurrying, cut so much as a single corner or you will be sorry. To do this — is to be an American in the best way you can; and if you should doubt what I am saying, simply and try it and see whether the result is to your liking. I suspect that it would be.

For the nervous man is a man without myth; he has no style and no higher purpose. If he has had the virile spirit of masculinity etched into his flesh it is for no good purpose; if he has been born under the Stars and Stripes it is only for bureaucratic purposes and nothing else. Such a man is only a “human resource,” and God help him. To avoid his fate you must only avoid the thousand traps that exist to force you into his plight; and chief among them is overthinking. If it seems I belabor this point, it is only because it is of such incredible importance — sprint into myth and into a world of primordial powers and spirits above all; sprint into the good world handmade by God, a world whose mode of action is supernatural more than it is purely measurable and rational. Banish the mind if ever the mind should threaten the spirit, and you will be made whole in your manhood.

In striving toward such high and indescribable ideals as these, make keen note also of the land. For in our time, we are an anomaly in the sense that the land is no longer a central and requisite component of ourselves and our lives; but nevertheless, its incredible, immutable degree of constancy can act as a perfect rudder on your journey. The slate ridges of the Appalachian Mountains are worn on the faces of living men; the aridity of Western deserts is discernible in the eyes of their inhabitants. There are men of maple and men of oak and men of spruce — there are riverine fellows and islandmen and men who thrive on the flesh of lake trout and moose. Such creatures as these wear a style that is not solely of their own invention; they borrow style from the land for so long that they become the very fruit of that land. And so, if you find yourself traveling, I will tell you that the cities will offer you little, for they so seldom contain citizens who live by these truths. Find the land that speaks not merely to your mind nor merely to reason but the land that flies up through your spine and bones — and wed yourself to it as a suitor is wedded to a maiden.

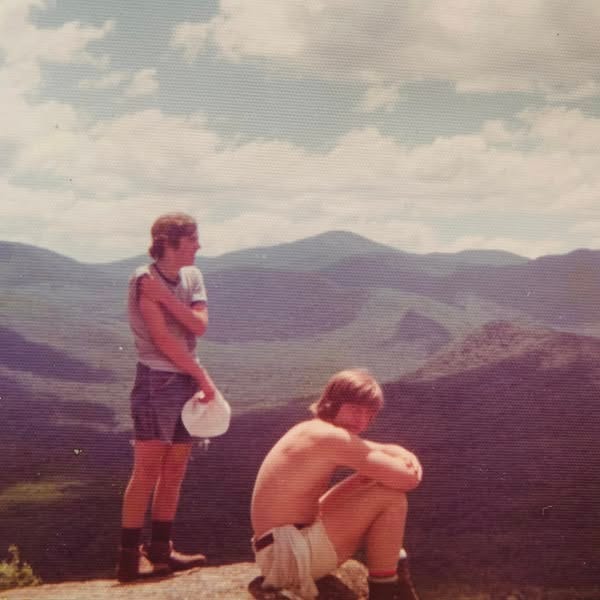

In all this, if you find any one thing to be true, beyond God, beyond nature, beyond the immutable truths buried within you both as man and as an American — I should think you will find sublime truth in the act of walking, and at that, of walking overland. Truly, my friend, if you find yourself at your wits’ end, whether now or in seventy years’ time — consider the mantra of the great Saint Augustine, who famously said solvitur ambulando, which is Latin for “it is solved by walking.” The weightier your burdens, the longer your walks must be; if circumstance binds you to a particular place, or has only given you so much time, you would not do poorly to spend all of your free waking hours walking in lonely places. Better than this, of course, is to be unbound by time or place, and to walk a continuous, unbroken path in a single direction, day in and day out. In such a journey, the body arranges itself as holy God has meant it to be arranged, and following this, the mind and heart go in likewise fashion.

For the automobile, the aeroplane, the train, and all of this sort of thing — they are frankly hazards the likes of which I rather wish I had avoided in my years of travel, and heaven knows I avoid them now. They move faster than the soul can move, and fragment the spirit, shaving parcels of it off with every hasty departure. Far better to move as God intended, foot over foot, breathing as you step, lucid, sober, simple, even prayerful as you go. And truly, if I must give you any prescription for how you are now feeling, and what you are now wondering about, it is only to follow your instinct, and to heed the very words you yourself said to your dear mother: to get up in the night and just start walking.

Along the way, the heavens will show themselves in the briefest, most sublime flashes — you will see what it is that I am saying if you should think to go and do it. The mind will settle out; what blows have ever been dealt to your heart will scab over and heal — your body, your heart, your style, your ambition, all of it will be revealed in the silence of a long and solitary walk in this old country. Much of what you’ll see will be ghastly and untoward, and on that score you can be well-assured, but what you will see underneath it all will cause your blood to rise in a way that cannot be undone. You may find yourself in thunderstorms with ripped tents and soaked blankets; you may find yourself drinking ale with antique men from former eras — you may even find yourself holding hands with the woman you’ll one day marry. It all begins with a simple, bold, courageous trust fall upon the long road, and with a prayerful breath to begin each morning dawn. Armed with this, you will thrive, and I am certain of it.

There is much else that I could tell you, and perhaps a time will come when I will do just that. For now, it is my hope that what I have written here could be of some use. These are not straightforward things to describe, not by any means, and so forgive me if any of what I’ve written here has seemed strange or off-color. I simply feel a good deal of passion on the subject of young men and their often difficult, strange plight — for we are, as I said, living in a strange and difficult time. By the same token, of course, there are dimensions in which this is one of the finest times a young fellow could be alive; after all there are now houses for sale for practically nothing (the villages are full of opportunity) and food is extremely cheap by historical standards. Jobs are everywhere in the US, if you’re willing to travel, and I know for a fact that there are many fine women a young man could marry who, in former times, bachelors would’ve been fighting over. In spite of the difficulties that this era might present, there is a great deal to be found in the way of opportunities for any spirited young fellow.

So, I say, go with gusto and with great passion — and if you should want any specifics on the fine art of vagabonding, hitchhiking, camping, or what have you, know that I will promptly reply to anything you should write me.

Warmly,

A.M. Hickman

Let this essay be added to the American Canon. I myself am about halfway through this depicted journey--about halfway in age between writer and intended reader (I'm 25)--and I can say with certainty, consequently, that half of this essay's "advice" (though I know that's not what it's necessarily intended to be) is 100% sound and that the other half is exactly what I'll need for the second half of this young manhood journey I am at current partaking in. Incredible, incredible essay.

“sometimes I want to get up in the night and just start walking.” - At 67, I still think this every single day. It is a blessing to live in the same time as you, good sir.