My friends,

I write from a motel room in Elko, Nevada, where we’ll be for the next few weeks. This room was paid for by the Paid Subscribers of Hickman’s Hinterlands, and I want to express my sincerest thanks. After eight straight months of traveling, my wife and I have been in great need of a quiet, warm refuge in which to recoup, and above all — to write. Lately it has been a challenge to regularly post here, as both holiday festivities and travel have distracted us. But you have my word that in the coming weeks, there will be many more posts to come, the bulk of which will be about our recent travels around the United States.

I should also note here that Hickman’s Hinterlands has surpassed a major milestone — this publication now has more than 10,000 Free Subscribers! Thank you so much for your support and faith in this work; I am greatly emboldened by it.

This week, in the spirit of Advent, I offer a meditation on faith. Because I am a Roman Catholic, I write from a Catholic perspective — but I will say in advance that my reflections here should prove worthy of consideration to people of all backgrounds. Faith is the force that has led men to build great things, to settle distant lands, and to compile the inheritance of knowledge, moral order, and beauty we still enjoy today. Let this essay be read as a sort of prayer that the faith of men the world over should never die.

And now, I give you “Ave Maria!” —

This is why Catholicism is great: It is human. The dirty street under hanging gardens, the red wine hangovers, sun-drenched Crucifixes and lugubrious nighttime prayers — at the table, the Catholic's humor is dark and droll. He takes his meals sumptuously and with great gusto. He holds a skull and laughs. To the Catholic, the most precious Blood of the Lamb waters the flowers and sweetens the wine. His God is the salt on the meat and the seed on the field and the moonlit blood of the martyr. Death frosts his every delicacy.

For him, the streets swirl with violence and grandeur, marble and paupers, cobblestone and lace-fringed processions. Misfortune boils out of the human sphere, and almost involuntarily he mutters 'Ave Maria!' at every disordered act of his fellow man.

Contrawise, the Protestant1 has an ambition that is every bit as laudable as it is misguided — to 'smooth over' the Fall of Man with barrenness, white walls, the complete infallibility of Scripture, total sobriety. Pagan origins of European man and his diaspora, mumbling to the Saints, fumbling Rosaries for souls in purgatorio, the rambling fatherhood of Il Papa, Latin pomp and bloody images of the Passion — all of it is too human for the Protestant; too messy. He regards all such ‘Romishness’ and ‘Popery’ with intense suspicion and even scorn. He may sit in the barn, reading and re-reading, shunning drink, trapped in an eddy of sober sinlessness, convincing himself as much as his neighbor that his fervent, feverish ambition for perfection could even be possible. His haunting hymns bely his weird anguish; his schedule of endless toil has been laid out as his only form of release.

To this, a Catholic winces while laughing, raising his eyes in wonderment at the stone grotto arched above Our Lady, muttering some dry witticism with beer on his breath, shuffling back to Mass as if by pure unthinking instinct. And afterward, he says to his compatriots (even the Protestant) — "Let's eat."

He says this with the confidence and apblomb that could only be mustered by one who has just consumed the meal, the only real and necessary meal on earth — the holy, spotless Eucharist.

In this sacred meal, all things blush and dance and do their curtsy before the Lord; their nature is exposed as another of many delicate brush strokes of the divine Master. A convergence of all things on the good and hallowed earth takes place as the host is raised and the grim clouds over the Church open into smiling sunlight; and in the pew, a man's flesh stumbles over itself. His sins are rippling, clumsy things that stand between his soul and his Creator like tippling, rusty hurdles.

The Matroyshka doll of his layers altogether conspires to prevent him from entering into the hand of his God; first, the lazy, red-eyed rising from bed, then the bumbling action of his fingers above his shoelaces. The slush on the walk to Mass makes him think to turn around. “Ah,” he mutters, “I am too tired to go” — but he goes anyway. He stands by the Church door smoking a cigarette, cackling with the old coots, thinking he'll not go inside until the homily — but ah! The statue of the Virgin beams at him across the frost on the churchyard's surface, and like a shamefaced puppy he tiptoes in as the Mass begins — Ave Maria!

Then, he is distracted, trapped in worldly concern and worry. His wife is on the fritz, or no — perhaps she isn't, and shame on him for imagining it. The blasted washing-machine is a worthless hunk of metal; the payments are due. His sweet little child said the word yesterday — a dirty one — and what ought he do about that? But like the ringing of the schoolbell jostles the sleepy-eyed student from his idiotic reverie —

"Lord, hear our prayer."

And his ears perk up; he is remembering something now. He has stopped gazing out the stained-glass window.

"Pray, my brothers and sisters, that your sacrifice and mine may be acceptable to God, the Almighty Father."

His mind returns; he stops fiddling with his tie, and he responds with a stern and manly resolve in his voice:

"May the Lord accept the sacrifice at your hands, for the praise and glory of His Name, for our good and the good of all His Holy Church."

Now the piss and vinegar within him drains down into his heart to be stilled and quieted and even consoled; he is 'locked in.’ His eyes are fixed upon the altar and his mind has ceased to shamble through the byzantine corridors of his own worry. The silence soaks him — he is removed from the bruised and blemished world of humanly things. And the bread is raised to the sound of the bell; the smoke of the incense rises into his nostrils, and he is dead — dead to the world. Lowering his head, he understands that he is in the presence of Jesus Christ; that the greatest of mysteries is indeed found in the mysticism of the Eucharist. He begs before Him; he remembers his somber confession — he shrinks back into the hoary, cold world of his own conscience, finally rising without noticing it, kneeling before the altar in a heavenly fugue.

And upon his hopelessly human tongue he receives the body of our Lord Jesus Christ, the God who is love itself, the God who created man and would come down and suffer alongside His own creation out of supreme benevolence. Our man floats back to his pew as if living in an infinity of miracles, swirling in the vortices of the Angels and Saints. He raises his eyes at the stolid countenance of Saint Joseph, who holds the Christ-child in his arms — carpenter's arms — and the incense has by now ascended into the atriums to form its own divine weather system. Though he is a grown man, his eyes gleam with the purity of a child.

After the final blessing, the organs blare, the impenetrable and dour Priest cracks a Mona Lisa smile — the first of the day — and suddenly he is bobbling about with droll men in suitjackets, noticing the lines on their faces as they emote as unreservedly as men can emote. They are smiling, for in spite of the gravity of sin and the ever-present lure of disillusionment and anomie, on this morning, they have risen from the foxholes of their darkness and have been led to hope. Now the cycle shall begin again, first with Monday's humor, then with Wednesday's wrath, then with Friday's gluttony, then with tears by the silk curtains of the confessional — and again, they shall find themselves drawn back to Mass again, as if by magnetism, for the architecture of their very wills has been crafted into a Cathedral of the mind and heart.

These men are Catholic men; they are men whose spirits fly through the pipes of the organ and whose flesh is washed from hot to cold like the wool in the feltmaker's hand. The trajectory of their lives is in place, and they can only oblige it lest they sputter out into the howling wilderness of the apostate — out into the world where men no longer wear suitjackets, where every sin they once confessed eclipses the weird and inaccessible virginity at the core of the heart, forming them into ghastly and clownlike caricatures of human men. At such a thought our man ejaculates in prayer — Ave Maria! — and finds himself strolling into the parish Church yet again.

Such a world as that of the Catholic is a world of sauntering romance — for let us not forget that "romance" finds its etymological root in Rome; the city that would bring the sumptuous dramas of Catholic life out across the earth. One can hardly think of romance or romanticism without deferring to that great city; the city where the apostle Peter was sent by Jesus Christ. Peter's bones are still there, and the supreme sublimity of all things Roman seems inextricably tied to those blessed bones.

Now, when we speak romantically about a thing, or a person, or if we find ourselves entertaining ideas of things that are romantic — we understand (or should understand) that there is a flip side; for romance has within it a seed of heavenliness that cannot survive in the harsh world of mortal men. We find earthly delights and pleasures and they are profound to behold and even strike us as hopeful — but we know just as well that they may contain the seeds of our disillusionment and sorrow. And so it is that when we begin to romanticize anything, we are remembering the cycle of heavenly, hopeful boldness in the human mind and its Janus-faced converse — the tears that well up in the confessional; the morbid defeat of hunger, sacrifice, and sin. Anyone who is a romantic is, at their core, wandering through the gardens of the Vatican in their mind whether they've ever stepped foot in a Church or not. The question is whether they are equipped for the dark side of it, as practicing Catholics are and should be. Often enough, those outside the Church are not.

Strangely, it is this romance that seems to have a remarkable capacity to lead men and nations to build and do in way that has no equivalent or comparison anywhere. For as Antoine de Saint Exupéry — a Frenchman and a Catholic — said:

“If you want to build a ship, don't drum up people to collect wood and don't assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea."

To long for any ideal vision of anything is, as many modern people seem to be fond of saying — quite dangerous. For one's longing may indeed be fulfilled; but it may just as quickly expose the object of one's longing as a darkening thing, or a non sequitur, or an immiserating chain of pointless sufferings. Far better to — lest we are tempted to veer into "dangerously romantic" territory — to long for nothing in particular, to pass through this life as a bloodless observer for safety's sake. This seems to be to be the thesis of so many slick moderns, 'scientific' secularists, therapists, and clean-heeled 'rationalists.'

And in the case of the "endless immensity of the sea," as Exupéry mentions, this is a particularly good example — for death by drowning or scurvy seemed to be the reward for so many sailors' oceanic dreams. The misery of being tossed about below-decks in a maddening storm, the torment of being caught in the doldrums or doused by violent rains — the long, endless voyages during which one will not catch sight of a bird, much less a woman. These are the rewards for a sailor's romance.

Yet such sailors would not only change the world forever — they would articulate the beauty of what men with a fervent vision are capable of achieving if only they should have the bravery to tackle the accompanying sorrows headlong. This should, in and of itself, count among the highest vocations in human life — and it begins with an impossibly ideal vision the likes of which more 'sober-minded' folk would dismiss as foolish, doomed, and unreasonable.

But just as blood is drained from the dissectionist's pig for the sake of cleanness, legibility, and experimentation — the longing Exupéry describes seems to have been drained from the sons and daughters of the West in witheringly short order. Just as quickly as one can walk out of a parish Church, they can go and trade the dramas and romantic mysticism that has ever led men to real passion for a blockheaded sort of practicality. Vision falters, "tasks and work" comprise the essential structure of his every effort — and the work is more tiring than it was before.

So began the West's descent into languor and acedia.

Now, it is only the monstrous thrust of the space-ship that ever catches the passionate, romantic eye of a man — though I suppose the exponents of that sort of thing seldom imagine that Netflix would get every bit as boring on Mars as it is down here.

Until that lesson can be learned — if it ever can be learned — we find ourselves mired in a culture of "laying down in easy places," as a lyric from an old Folk Punk band goes. A certain exhaustion at the world of "tasks" creeps in, and an escape from that exhaustion is the only sort of vision that men now dream of in daily life. Once, the hallmark romantic vision of former generations was found in the erection of Cathedrals and the mastery of self against sin or against earthly ravages in great journeys; man found himself living through a story of overcoming, eroticism, and beauteous struggle with and towards the Divine.

Now, our dreams seem only to be tepid visions of a "house by the beach" or an early retirement. We have collectively transitioned into a mythological stage that is stripped of its Faustian spirit in this way; where once our fantasies were imbued with a willingness to confront the sublime and the horrifying all in one swashbuckling slash, crying “LIFE!” — now, we live in a pallid, neurotic world of fantasy without romance.

This difference may indeed be the difference between those who build great things and those who merely seek to live in the shadow of the great things others have built. It is the difference between the men who built San Francisco and the men who, today, move there because San Francisco is already ‘cool.’ For where the romantic creates madly and without regard for cost, where he cycles between the ecstasies of birthing beauty and long sojourns into sorrow, the man whose vision is only an easy fantasy is a consumer. He shuns the days of ice storms, shame, and hunger; he shuns the confessional, the “judgement,” and the paternal safety of Christ — and he slinks into a languid, passionless state. He does not live the “high highs and low lows” of his forefathers but paralyzes himself into a rut of comforting constancy.

Here, he is in control; he is never judged, and never hungry — but conversely, he does not wed his action to a transcendent vision. If he builds anything, he labors only as a fungible, abstracted ‘contributor’ to an inhuman scheme of technics, usury, and efficiency. The modern man is, then, a withered creature. Made in the Image of God but having turned away from Him, he is reduced to a tired shell and little else; he is shuffled off into the province of faceless machinery, finding his only reprieve in vacations, or in revolutions (which are really like little vacations). Life for him is tragically reduced to a sort of video game of “economic utility” and little more — for he has wandered away from the heavenly vision of the Virgin and the mystical beauty of her infant Child. Modern man has, by a ghastly accident, come to prefer concrete to Cathedrals.

Just shy of a year-and-a-half ago, I made a post on Twitter that went viral:

In Lansford, ND, you can buy this house for $15k. It's a little rough but livable. In the same town, Northern Plains Railroad is hiring for $25-28/hr for a Utility Mech. No experience required.

There's no 'housing shortage' — there's a shortage of imagination and flexibility.

The post got over nine million views, and the opprobrium it caused was stunning: thousands of commenters flew off the handle, decrying small-town North Dakota as “a frozen shithole,” “boring and flat,” and declaring my suggestion as “brain-dead,” “disgusting,” and even “racist.” I received dozens and dozens of enraged direct messages. I even got death threats! The official Lansford North Dakota Volunteer Fire Department Twitter account replied as well, pridefully informing the world about the “greatest fire department in America,” and the Fire Chief himself invited me to Lansford for a free weekend stay in his rental apartment. Bizarrely, one reader even used the Tweet as the basis for a piece of homosexual erotic fiction. The aura around the discourse on this small North Dakota town, population 238 — was downright delirious for weeks, and I was genuinely amazed.

But hundreds more commenters applauded the idea, saying that it represented “the best of the American spirit,” and offered a realistic path forward for anyone fed-up with big-city housing costs. They also pointed out, correctly, that one wouldn’t even need to stay more than a few years to build some savings and equity before going back home to settle there. “Be careful if you come to Lansford,” one local commenter said; “you just might get addicted to the best waterfowl hunting in the Great Plains.” Another said: “Americans are now too locked into dreams of status to ever consider moving there. Their loss!”

One idea consistently cropped up among the optimists that I found inspiring and true — the recognition that not so long ago, there were people who would do anything to settle in North Dakota. Boatloads of Norwegians, Finns, and Americans from points further east fled the hovels of their homelands for a chance at a “frozen shithole” on the icy Dakota plains, descending upon the prairies in hordes. They often arrived dirt poor, with large families in tow, and many settlers of urban extraction learned how to farm on the spot with no experience. Some died, some left — but many lived and stayed on. Those who succeeded did not arrive in search of a cheap, low-risk, easy fantasy: They arrived with a vision that they pursued with intense vigor and insistence — they embraced the good, the bad, and the ugly of their new Dakota life and overcame all, fighting the subzero chill for their daily bread, dwelling in sodhouses, and setting into motion one of America’s greatest stories in her rich history.

What remains of that incredible effort are hundreds of villages dotting the plain, surrounded by some of the most productive agricultural land on earth.

At the center of each is a Church.

Now, the villages are emptying and the Churches are often vacant. To mention moving to the Plains to anyone under 35 elicits jeers and ridicule. North Dakota is, in spite of its wealth of opportunity and gorgeous scenery, simply unattractive to most Americans today. As one North Dakota local told me in a DM after the Lansford Tweet went viral: “My grandpa has pointed out to me that as soon as the Churches started going empty — people started moving away. It all happened within his lifetime.” I found this Dakota grandad’s view quite telling; perhaps his analysis of his own state could shed light on the decline of other rural American regions.

Perhaps the answer to the decline of America’s rural heartland regions is not to be found in grants and subsidies or ‘artist loft’ complexes in our downtowns; nor in remote work, or corporate investment, or tourism. Perhaps the revival of our rural hinterlands requires only a return to the romance and mystery of the fervent faith that ever settled these regions in the first place.

For at this stage of our country’s economic history, there is no ‘rational’ reason to live in far-flung backwaters which lack tourism or development. To willingly go where there are ‘no jobs’ is considered a sort of insanity, and by the standards of the secular-modern philosophical system — it is insanity. It is only great romantics and mystics who seem capable of delving into insanity; of embracing it and wrangling it into an edifying and profitable thing — and no doubt, when they should turn to do so and begin to build in our dearest rural counties, their efforts are not liable to dry up too quickly. For what they build requires no grant-writing, nor foreign investment; it requires no fiber internet connection nor luxury hotels — it is sustained by God alone; and man is only the humble tool of the Master, oscillating between ecstasy and ruin as a servant of God humbly does.

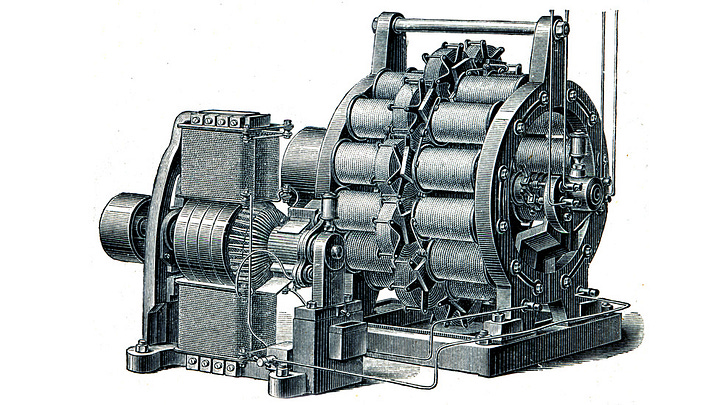

In the year 1900, Henry Adams — a descendant of President John Adams — ventured to Paris to view the world’s Great Exposition. His dear friend Samuel Pierpont Langley showed him various exhibits, including one displaying some of the earliest electrical generators, called ‘Dynamos.’ Here, I will offer some lengthy quotes on his reflections, from his autobiographical work The Education of Henry Adams, which seem to me to be being strikingly germane to the subject at hand:

[Langley taught me] the astonishing complexities of the new Daimler motor, and of the automobile, which, since 1893, has become a nightmare at a hundred kilometres an hour, almost as destructive as the electric tram which was only ten years older; and threatening to become as terrible as the locomotive steam-engine itself …

Then he showed [me] the great hall of dynamos, and explained how little he knew about electricity or force of any kind, even of his own special ‘sun,’ which spouted heat in inconceivable volume …

To him, the dynamo itself was but an ingenious channel for conveying somewhere the heat latent in a few tons of poor coal hidden in a dirty engine-house carefully kept out of sight; but to [me] the dynamo became a symbol of infinity. As [I] grew accustomed to the great gallery of machines, [I] began to feel the forty-foot dynamos as a moral force, much as the early Christians felt the Cross. The planet itself seemed less impressive, in its old-fashioned, deliberate, annual or daily revolution, than this huge wheel, revolving within arm’s length at some vertiginous speed, and barely murmuring—scarcely humming an audible warning to stand a hair’s-breadth further for respect of power—while it would not wake the baby lying close against its frame. Before the end, one began to pray to it; inherited instinct taught the natural expression of man before silent and infinite force. Among the thousand symbols of ultimate energy the dynamo was not so human as some, but it was the most expressive.

Yet in spite of his willingness to grant that these machines were indeed awe-inducing, he admitted his interest in them was more in their “occult mechanism” than anything else. He seemed naturally to draw spiritual conclusions about the strange contraptions he viewed at Paris:

No more relation could [I] discover between the steam and the electric current than between the Cross and the cathedral. The forces were interchangeable if not reversible, but [I] could see only an absolute fiat in electricity as in faith. Langley could not help [me]. Indeed, Langley seemed to be worried by the same trouble, for he constantly repeated that the new forces were anarchical…

Finally, a discomforting conclusion welled up within him as he continued to stare at and study these mechanical behemoths and the feverish men who presented them as God-like entities. He’d only days before paid a visit to the Cathedral at Chartres, and the juxtaposition between the whirling Dynamos and the high-flying stone arches of the Cathedral struck him. He mused:

All the steam in the world could not, like the Virgin, build Chartres.

For where the steam wafting through the rotors of the Dynamo was the product of a sexless, industrial rationalism — a passionless, nearly autistic sort of ‘sensemaking’ devoid of fever and flesh alike — the figure of the Ever-Blessed Virgin Mary looms large in the fervor of Cathedral-building men. Even Adams — who was raised a Unitarian and was far from being a Catholic — could not help but admit the potent truth of the Virgin in the inexplicable strength and genius of the Western world. Later, in his 1907 book, Mont-Michel and Chartres, he even argued that the ‘masculine character’ of modern machinery was a destructive force that would result in the decline of Western society. Without the Virgin — we would find ourselves doomed.

For the Virgin Mary is a trove of mystery and profound beauty; she herself is a commentary on the character of God. A model for all women; the true and sinless Handmaiden of the Lord — she is the redemption of Eve. In her, a man sees a mirror of himself: If he is a sinner, he might think only of her virginity, and haughtiness may fly up into his craw like a devil — but she, in her blessedness, intervenes like a mother does; she grabs him by the hand and leads the wayward lad to the wellspring of truth and eternal love, and there, a wayward boy awakens to virtuous manhood. If a man strives to please God, who has instructed us to “honor thy mother and father,” he yearns for her blessing and comforts; he carries great weights to please her, shouldering timbers for the sorts of Churches that his distant offspring will praise one day as ‘world wonders’ the likes of which our ‘rational’ architects can no longer even conceive of constructing.

Reverence for the Ever-Blessed Virgin Mary seems to be, as Adam Van Buskirk said, largely congruent with machismo. Strangely enough — she is venerated in cultures where the men take great pride in their manliness and strength; yet by their faith in her Son, this manliness is well-ordered and clarified into a civilizational potency that has no positive equivalent in modern secular society.

If there is any equivalent to ‘the Virgin’ in today’s world, it is only in the negative — it is the shimmering, digitized, silicone whore one finds in pornography and among so many celebrities. It seems the ghost of Eve has returned, or a demon has floated into the flesh of our boys and men, drawing them down into a mire of pointless darkness. Our feminine ideal is, now, the “anti-Mary:” the glistening ‘beach babe’ one finds on their dearly-beloved ‘vacation’ to our Miamis and Ibizas, and indeed ‘the whore’ is a sort of vacation in and of herself. She is the sultry, dark-eyed temptress in whom only a mire of pointless lust and pharmaceutical infertility is found. “She” is the very portrait of hell itself, almost precisely for the very ‘rational’ basis on which her beauty and value is judged.

Where the “anti-Mary” is a deceptive, surreal “10/10” — the beauty of the Ever-Blessed Virgin Mary flies high into the heavens, far beyond numbers and catalogues of plastic features, into the world of mysticism and passion — beyond measurement; straight to the foot of the Cross.

It is with her blessing and prayers, I might hope, that mankind has the hope of ever opposing Dynamos and automobiles and ghastly, frightening concrete edifices. By her intercessory prayer have men ever fought Communism and nihilism and murderous notions of false, ‘rational’ utopias which seek to denature the very heart of man; traveling at the side of the Virgin, they dream far beyond the ersatz fruits of commerce and witless ‘prosperity,’ impoverishing themselves of earthly delights and wandering out into the heaven-on-earth one finds in the Eucharist. This is, by all I have gleaned, the architecture of a faith which makes life hyper-real; sending man into the highest realms of his own capability and belevolent power. And so I say that Mr. Adams was, so far as I can tell, dead-on with his assertion that “all the steam in the world could not, like the Virgin, build Chartres.”

Many will object, I should think — and understandably so — that my thesis here could be read as a chauvinistic, triumphantly Catholic sort of essay and nothing else. To the contrary, whether one is a Roman Catholic or not is only of oblique import to what I am suggesting here. While I would hold, as I am duty-bound to do (not only by my faith but by my reason, too) that those who understand the thrust of the arguments I’ve presented here would, in time, have no choice but to convert to the faith built upon the Chair of Peter — I do not write this to convert so much as I write it to suggest that the revival of passion is the most integral ingredient required for improving society in any manner whatsoever. Whether such a society is Catholic or not, I hold that this axiom would be true in all cases.

For passionless managers and joyless bureaucrats can make all the ‘sense’ in the world; they can be as ‘rational’ and ‘scientific’ as their duty to a dead and numbered sort of truth would demand — but their efforts mean nothing if they do not rouse the heart with potent art and myth and literature. And more than literature and art, it is the myth — the myth that ascends to a position of hyper-reality in the souls of men; the myth that is reborn in the heart as mystery and mysticism. Without this, nothing can be done, and we are paralyzed: we are, absent such vibrant passion for the sublime, condemned to languish in our present state, and far worse.

To have the sort of vision required to forge out into the hinterlands and far-flung backvelds is not a thing of the mind or of the will so much as it is a thing of the spirit. To laugh — and at that, really laugh — as one dines, in the company of Catholics or Muslims, Orthodox or adherents to the nameless, modern, secular religion; one must have a blossoming heart which traces the line between sorrow and sin and repentance and heaven all through the hours of its days. Above all, what I am writing about is larger than Catholicism in its strictest, most parochial sort of sense (and I do mean parochial). It is an inspection of the forces within the heart that, when loosed, give birth to ecstasy, fertility, creation, and a passion for risk, and beauty, and divinity.

Without that ‘thing’ — ineffable as it may seem to be — mankind and his societies are only liable to fade into mechanical oblivion. I must thank God here, in closing, that the situation is not, and can never be, completely hopeless.

Ave, María, grátia plena,

Dóminus te cum.

Benedicta tu in muliéribus,

et benedíctus fructus ventris

tui, Iesus.

Sancta María, Mater Dei,

ora pro nobis peccatoribus

nunc et in hora mortis nostrae.

Amen.

I mean for my comments here to be taken with a spirit of good-natured jocularity and not as some kind of nasty denouncement; I certainly harbor no ill-will toward our Protestant friends, nor, for that matter, any bad feeling toward our secular friends as well. My only ambition here is to shed light on ‘the Catholic mind’ — apologies in advance if you should find my styling of that idea here to be offensive. I quite hope you do not.