In Praise of 'Chaw'

To Revolt Against Modernity, Throw a 'Lipper' In

Fine-cut moist snuff tobacco looks like dirt. One opens the tin of dip and the room immediately smells of spicy manure. To pinch the wet, greasy, jet-black ‘dirt’ and actually dare to wedge it between one’s gum and lip takes at least a little bit of courage. This is because it is an objectively repulsive practice in basically every regard, as even the saltiest lifelong ‘dippers’ will generally admit.

And yet, to the chagrin of my lovely wife, I cannot help but indulge in the stuff at least once in a while. Copenhagen Long Cut, natural — the kind that comes in the little brown, round waxed-paper tin with the metal top; that’s the stuff. Pure tobacco, without any mints or wintergreens or peach-iced-tea kiddie flavors — the sort of thing favored by soldiers, ranchers, and hard-boiled beat cops. I run my thumbnail along the paper seal in one motion, hearing the paper hiss as it cracks open, and the distinctive ringing of the metal top clangs open rudely. All at once, the foul, leathery scent rises in humid curls of fetid air, and I place the portion under my lip with abandon, smiling a dirty, black-toothed smile.

This unfortunate habit of mine is an artifact from my desert days. A cigar smoker for years, supply chain issues and an abject lack of funds kept me from finding my brand of smokes anywhere. Worse, I’d been camped out at an old gypsum mine in the Sonoran Desert miles from any town. And so I began to suffer from vicious nicotine withdrawal — a hellish affliction that one can only understand if they’ve been through it. Those around me offered cigarette after cigarette, but much to their confusion, I wouldn’t accept. My suffering only ended when a man from Nebraska mercifully offered me two tins of Copenhagen natural long cut, and it was off to the races from there.

I never liked the idea of a cigarette. Sucking smoke down into one of the most important organs in the body has always struck me as a damn-fool thing to do. Moreover, as compared with the oral use of tobacco — whether one dips, chews, or ‘puffs’ the smoke of a pipe or cigar — it has always struck me as being dishonest. Where the dipper and the cigar smoker alike both make a decision to wear the ravagement of their tobacco habit openly on their own visage, the cigarette smoker hides the same filth and grime deep down in his lungs. If he thinks himself ‘classier’ than those who chew tobacco, he’s deceiving himself — his habit is every bit as disgusting, even if its worst effects take place way down in organs he’s never seen and never will.

Nonetheless, the cultural cache surrounding cigarettes has been, until fairly recently, associated with class and even elegance. I’ve heard that while chewing is for rubes, smoking cigarettes is civilized — modern. Chewing is an antiquarian holdover from the foul, dismal, barbarous ‘early days’ of American history, or so they say; the idea of plucking up a gob of natural tobacco and putting it in one’s mouth is, I guess, infinitely more repulsive to most than purchasing a carefully-machined paper tube of tobacco (and ‘recon’ — paper dyed to look like tobacco) and inhaling it into the lungs to blacken them.

For those who understand the real thrust of modernity, this prejudiced and incoherent view shouldn’t be hard to believe. So much of the project of modern times has been to tidy away the grisly and unsettling realities of the natural; to winnow down the savagery of the past into a neat, clean, pearly-white-plastic package. From buttressed Cathedrals to Soviet concrete, from the cacophony of the wet market to the self-checkout, from the feverish pageantry and sacramentality of wedding rituals to the nervous conjugal boredom of “keeping it casual” — modernity seems to have been a corrosive applied to the old, blustering, often arbitrary (or even Barbarian) life of God, nature, and Western culture.

Wolfgang Smith writes in the opening paragraphs of his 1984 work, Cosmos & Transcendence: Breaking Through the Barrier of Scientistic Belief:

“Nothing appears to be more certain than our scientific knowledge of the physical universe. But then, what is the physical universe? We are told that it consists of space, time, and matter, or of space-time and energy, or perhaps of something else still more abstruse and even less imaginable; but in any case we are told in unequivocal terms what it excludes: as all of us have learnt, the physical universe is said to exclude just about everything which from the ordinary human point of view makes up the world. Thus it excludes the blueness of the sky and the roar of the breaking waves, the fragrance of the flowers and all the innumerable qualities—half-perceived and half-intuited—that lend color, charm, and meaning to our terrestrial cosmic environment. In fact, it excludes everything that can be imagined or conceived, except in abstract mathematical terms.

But where does this leave our familiar habitat: this ordinary, unsophisticated world, which artists have painted and poets have sung?

It is with a certain (and quite fervent) triumphalism that our ‘scientistic’ master-class has unfurled a project of intense rationalism and sophistication — in totally uncertain terms, the late 19th century reformers, utopians, ‘scientific’ moralists, and post-millenarian Protestants sought to trounce the sinful backwards squalor of the Old World, and to replace it with state-enforced purity.

Yet when Hank Williams Junior, in meditating upon a bandit who shot his Manhattanite friend in a holdup for forty-three dollars, speaks the primeval truth that is so completely intuitive to the American Scotch-Irish ‘Borderer’ descendant in his song A Country Boy Can Survive, he makes a strong and guttural counterpoint to the reformer’s hatred of tobacco, retribution, and violence:

“I had a good friend from New York City, he never called me by my name, just ‘hillbilly.’

“My grandpa taught me how to live off the land, but his taught him to be a bus-i-ness man.

“He used to send me pictures of the Broadway night, and I’d send him some homemade wine.

“But he was killed by a man with a switchblade-knife, for forty-three dollars my friend lost his life.

“I’d love to spit some Beech Nut in that dude’s eyes, and shoot him with my old .45, because a country boy can survive!”

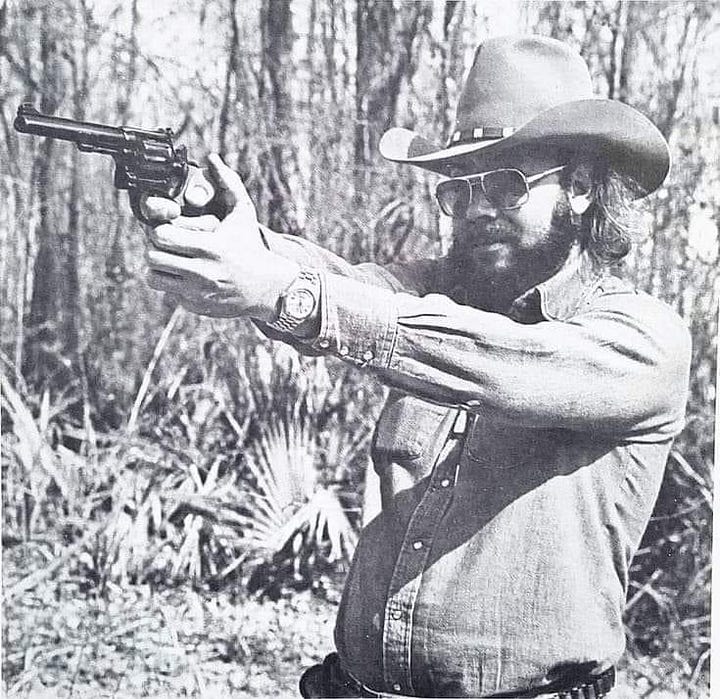

In hearing his lamentation over his murdered friend, the listener is drawn into Mr. Williams’ heady nicotine buzz from his Beech Nut brand ‘chaw’ — and is likewise pulled into his desire for homicidal retribution in the style of the ‘old days,’ where men take matters into their own hands. Where the modern, rational, ‘reformed’ man would have the bandit prosecuted, and would file his court documents in a sober manner — without one fleck of filthy tobacco in his tidy mouth as he does it — Hank Williams Jr. contemplates the delivery of swift and absolute justice on his own terms, doubtless abetted by his consumption of the mystical, warlike tobacco plant of his native Southern homeland.

In this respect, Mr. Williams brings to bear the full weight of the intuitive, ordinary, and unsophisticated world that Wolfgang Smith describes in the introduction of his Cosmos & Transcendence. As he strums the guitar, spitting the sweet, jet-black tobacco juice onto the dust in front of his porch, Williams revolts not only against the unjust, senseless murder of his New York City compatriot — he also forwards a complete revolt against modern society, abstruse scientism, and the ‘mechanical’ morality of the sleek, smooth, ‘enlightened’ champions of sobriety, ‘health,’ and bureaucratized righteousness. His insistence that ‘a country boy can survive’ is a declaration of his own perception and will against the machinic, faux-sophistication of Yankee Pietism — which he obliquely identifies, by implication, as one contributing element (or even the ideological culprit) of his friend’s murder.

I think of this as I lean back and feel the harsh burn of the tobacco in my lip as I write this. The nicotine courses through my bloodstream and I am roused to a sort of wakefulness that is more intense than organic, regular wakefulness — my mind is sharpened into a dangerous instrument by the crumbled black leaf in my mouth. The tobacco juice enters my brain like the shimmering humid heat of primitive Southern mountain ridges and remote Alpine zones; I close my eyes, spit the juice on the dirt underneath me, and mentally, I am hiding in a “laurel hell” with my own .45 in hand.

Something about this experience even recalls the original North American Indian warrior — who in his fiercest heyday performed a similar ritual as Hank did: rolling the fresh leaves of his beloved, sacred tobacco plant into a plug to suck upon as he readied himself for battle. Descending into the ancient realms of an ancestral, ethneogenic ‘buzz,’ the Chickasaw or Mohawk or Lakota did not only fly high above the measurable and scientifically absolute domain and into the province of his own intuition and perception — he heightened his perception into a sharper, more intensified state. The entrance of sacred nicotine into his bloodstream was central to his being and identity, not only for the pleasure it produces, nor simply for the increase of focus he experiences by it — but as a measure taken to make himself utterly illegible to the world of measurement, machines, and man-made systems. It is from this vista that he could then make war with famous tenacity and spiritual clarity.

Therefore, as one consumes the tobacco plant in its rawest, most original state, they engage in a quiet, firm, berserker-style revolt against the ‘Pure Reason’ that Kant so forcefully critiqued. And as this old-style manner of consuming tobacco wanes and becomes increasingly irrelevant, to insist on continuing to chew Beech Nut ‘chaw’ or to slip a portion of Copenhagen under one’s lip is to be aggressively anachronistic — it is to celebrate the primordial, primitive, allegedly ‘backwards’ frame of mind one enters by daring to put sweet chunks of tobacco in their mouth. It is not an understatement to say that this is not so much philosophical, at bottom, as it is spiritual. Both chewing and smoking tobacco, in this way, affirms an ancient, timeless, boldly primitive masculine spirit.

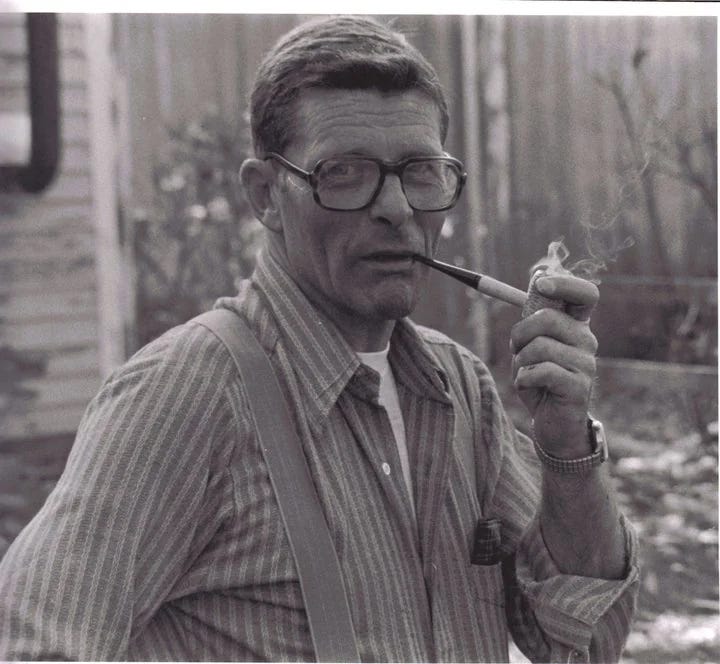

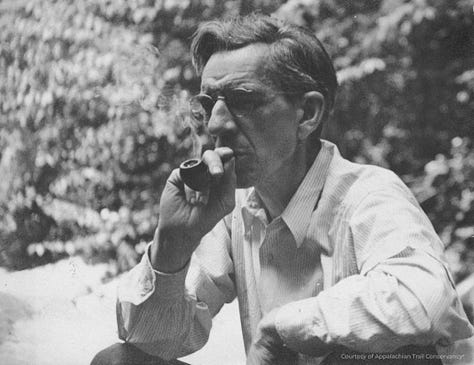

This revolt continued in the earliest era of the American pipe. By this, I do not mean the mass-produced clay pipes of German biergartens or English pubs, nor the absurd and precious Meerschaum pipes of French and Dutch aristocrats — I mean the American corncob pipe.

This was the style of tobacco use I first engaged with as a fourteen-year-old boy. Taking a cob of field corn up from the fields by the Mohawk River, I cut it in half and used my stepfather’s drill press to bore a large hole in it, and then a smaller one for the stem. I picked one of last year’s jalapeno stems from the garden that had completely dried, running a red-hot wire through its center to hollow it out. And then, I snugly fit the stem into the cob, filling the voids air-tight with bits of clay, and I sneakily baked it in the oven on an early morning before the schoolbus came. It was then finished into a true masterpiece of illicit teenage engineering.

Later, after school, I visited with my aunt and uncle — as my uncle was a very occasional pipe-smoker, and I knew he kept his fragrant tobacco in the bathroom. Wrapping a few measures of it in some toilet paper, I gingerly placed it in my pocket and rode my bicycle home. Finally, by the dying light of the sunset, I crawled onto a boulder in the center of the river, flanked on either side by two strong whitewater torrents of riverwater, where I packed my pipe and lit it with a match. The river sprinted in a deafening stream; the peeping frogs commenced their nightly symphony, and I blew smoke out of my young, inexperienced cheeks as the moon rose — slipping into a state of rippling, nicotinated madness, as if I were a frontiersman or a warrior or a scholar of an antique and inaccessible era.

So began my love affair — and a habit that still not only plagues me but delights me, too. Later, little hand-rolled cigars called “Banditos” would become a part of my daily ritual, too. Rough, stubby, Clint Eastwood style smokes, I’d order them online, directly from Hispaniola. In those days, one had no need to show ID when ordering tobacco from the internet, and when I received those large burlap bags full of oily, black cigars, I felt like Lewis & Clark on a reconnaissance run to Saint Louis for a supply of the vices that would take them clear west to Arizona. Standing out on the river, I’d bathe myself in the smoke and wonder at why the habit of smoking was so thorougly scorned and reviled by so many people. Such people even struck me as joyless and neurotic, all too taken with aggressively insisting upon a perverted and bleak sort of sophistication and false piety.

The cigarette revolution, of course, de-fanged the immense power of the tobacco plant in harrowingly short order. Upon the advent of this most miserable smoking device, all of the rough, organic, and un-civilized inexactness of ‘chew’ and the older forms of smoking was tamed with mechanical precision. Tiny white tubes — the modern spirit is obsessed with the parched cleanliness of bone-white absence of color — with pre-measured and weighed portions; styrofoam filters and plastic-wrapped boxes. No burlap, no improvisation, nor corncob, no work of human hands. Every cigarette is the same experience, over and over and over again: and it therefore inculcates in its user a peevish insistence on machine-like consistency and regularity of his experience. The cigarette-smoker is not the sort of man who can stomach the imprecision of his grandfather’s habits, and for it, he is groomed to despise the very imprecision in all domains of life that verily makes us human beings and not robots.

More recently, a development took place that I almost hesitate to mention because it is so abjectly ugly — it is called “vaping.” This verb appeals to the man who is trapped in eternal, video-game-style boyhood; he holds an electronic joy-stick and sucks the phony, futuristic “smoke” into his lungs, imagining himself to be the protaganist of a sci-fi film. His little plastic “vape pen” looks like a lightsaber or a Nintendo controller, and he treats it as his ‘binky,’ constantly sucking on it. His addiction to it is foul precisely for its removal from the life of organic, imprecise, unmeasured ‘natural-ness.’ The vaper literally breathes the completion of the modernization of nicotine, and therefore of human life in general — he is the all-too-willing Guinea Pig for an industry run by weird technological grifters and Utopians, who unflinchingly evangelize their product as the ultimate answer to scientistic criticisms of actual, ancient, natural tobacco.

I could make a similar criticism of those who use the oral equivalent — nicotine pouches that are sold under the brand of “ZYN,” “On!,” “Rogue,” and in Canada, “ZONNIC.” While I do use these myself, I must admit that they are hardly different from vaping — for they are an experimental, new-fangled sort of vice, consisting of plastic ‘pouches’ containing laboratory-grade nicotine dust. Many are flavorless, or even when they are flavored, offer the user nothing but his daily fix of nicotine. Were it to be that my true favorite — Swedish snus, which I will discuss at greater length in a moment — were more widely available, I would never use these stupid products; but because they are uniquitous, I unfortunately do use them.

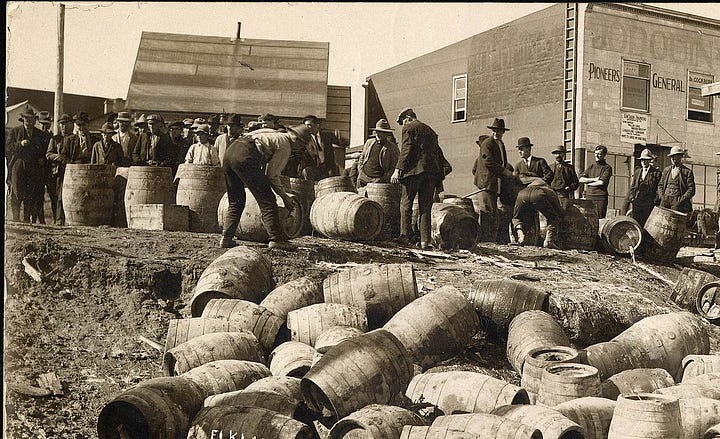

Following the ‘vaper’ and the ‘ZYN-er,’ of course, are the ones who abstain entirely from nicotine, in a latter-day rendition of America’s horrifying “prohibition” era — when various blue-bloods and Protestants took to a feverish moral crusade against the ancient beverages which Christ Himself consumed. Just as the fruit of the vine was regarded scornfully by the ‘reformers’ and Utopians then — even where such scorn boiled down to being only a pointless scorn for the very things that make us human beings — a more contemporary corollary is found the the anti-tobacco crusade, which seems even to include a scorn for “vaping” and “ZYNing” as well.

For while the descendants of ethnic America — our Micks and Guineas and unflinchingly Papist Frenchies and Spaniards — revel in life itself, there is another demographic in this country that seems more to revel in fierce moral crusading and a conception of social status rooted in self-righteous abstemiousness. Toward this end, this latter group will cook up almost any allegation against the happy pleasures of this earthly life — even resorting to bald-faced lies when the precise rationality they praise fails them. To describe the tensions between these groups, one really must examine the period of American history between 1840 and 1940 — particularly as it relates to the genesis of what came to be called “progressivism.”

Murray Rothbard — the eccentric “anarcho-capitalist” libertarian — wrote a thick, nearly-600-page opus titled The Progressive Era, which was published shortly after his death. In the book’s fourth chapter, titled The Third-Party System: Pietists vs. Liturgicals, he details the profoundly different points of departure that the American ‘WASP’ had as compared with their Catholic counterparts, borrowing two terms coined by professor Paul Kleppner in the 1970’s.

On the “Pietists,” he says this:

The Pietiests were those who held that each individual, rather than the Church or the clergy, was responsible for his own salvation. Salvation was a matter, not of following prescribed ritual or even of cleaving to a certain fixed creed, but rather of an intense emotional commitment or conversion experience by the individual, even to the extent of believing himself “born again” in a special “baptism of grace.” Moreover, the outward sign — the evidence to the rest of society for the genuineness and the permanence of a given individual’s conversion — was his continuing purity of behavior. And since each individual was responsible for his own salvation, the Pietists concluded that society was duty-bound to aid each man in pursuing his salvation, in promoting his good behavior, and in seeing as best it could that he does not fall prey to temptation […]

Society, therefore, in the institution of the State, was to take it upon itself to aid the weaker brethren by various crusading actions of compulsory morality… [they advocated] Prohibition, to eradicate the sin of alcohol… Sunday Blue Laws… and compulsory schooling to “Americanize” the immigrants and “Christianize the Catholics”… to transform Catholics and immigrants into pietistic Protestant and nativist molds.

The “Liturgicals,” by contrast, were puzzled at this aggressive and often State-enforced moralizing, and moreover were vexed at the notion that government-mandated purity could be imagined to have any kind of salvific power. For the Liturgicals, purity was a matter of how one exercised the God-given freedom of will — and in fact, could not be produced by compulsion or policing. Moreover, the hard-coded inevitability of sin described by the Fall of Man as they understood it led them toward a disposition that did not punish the individual for his failings with regards to a performative “purity,” but for heresy, or the refusal to remain within the bounds of his ancient and creedal theology. This was the case not only for Roman Catholics, but for certain Lutherans, high Church Anglicans, and other non-Pietistic Protestant groups.

Rothbard — who was not religious — said the following on the matter:

The Liturgical correctly perceived the Pietist as the persistent, hectoring busybody and aggressor: hell-bent to deprive him of his Sunday beer and his voluntarily-supported parochial schools, [which were] so necessary to preserve and transmit his religion and his values. While the Pietist was a pestiferous crusader, the Liturgical wanted nothing so much as to be left alone.

In this way, the central ethnic and religious conflicts of the Progressive Era of American history were not as strictly drawn on ethno-religious lines as many would imagine; the substance of these conflicts was, more than anything, connected to religious views on the issue of individual freedom with regards to the state. Many native-born, ‘heritage American’ WASPS, for example, were avowed Democrats — which was then the party of personal freedom — alongside the immigrant Catholics. Additionally, the “Southern Democrat” was also joined with these in an unlikely alliance for the sake of personal freedom — as their theology differed considerably from the Yankee Pietists with regards to the question of whether the state should enforce matters of purity and personal morality.

The Pietist model laid the groundwork for what would become modern secular progressivism, as their moral fervor began to slip further and further from an explicitly-Christian theology. These Methodists, Presbyterians, certain Baptists, Quakers, and later left-leaning immigrants from Eastern Europe would congeal into a political alliance, and as the 20th century pushed ever onward — they would all ‘secularize’ at the same time. Today’s political left is comprised largely of the inheritors of these alliances and movements, and as a result, many of our “blue states” still are in the business of finger-wagging and unfurling a triumphantly scientistic morality, over and against tradition, intuition, and human freedom.

What complicates matters considerably is the fact that now and again, the Pietists’ conclusions about how best to employ the state as an arbiter of morality and right conduct are actually correct. When Mayor Bloomberg illegalized king-sized sugary sodas in New York City, for example, the obesity rate of that city decreased dramatically in short order — yet this prohibition is decidedly Pietistic in its nature. And during the era where the activities of large American tobacco corporations came under fire, and cigarettes were discovered to have objectively ghastly health impacts — subsequent efforts to curtail cigarette usage had a very clear and measurably positive impact on American health. But again, the mechanism by which this change was brought about was fundamentally and, at times, rabidly Pietistic.

And so it is that, owing to their efforts and the undeniable truth of them — at least as far as cigarettes are concerned — I cannot defend cigarette smoking here or anywhere. The era of the American cigarette involved generations of pointless early death and hellish maladies of the lungs and throat; owing, no doubt, to the idiotic practice of inhaling smoke into the lungs. As anyone who has ever spent a good deal of time around campfires, wood stoves, or hot grills would know — inhaling smoke is something that every mammal should avoid under all circumstances. This was intuitive to me even as a child, when there were still smoking sections in restaurants — which disgusted me greatly.

Yet the dangerous thing about the Pietistic mode of social improvement is that once it picks up momentum, it is unstoppable — even beyond the point of the very reason that was initially employed to initiate that momentum. By this I mean, the crusade against the public health impacts of cigarette-smoking became a crusade against smoking in general, which was a grave category error — for the health impacts of cigar and pipe smoking are not even one-tenth as grave as that of cigarette smoking. In one study of pipe, cigar, and cigarette smokers in 1964, it was even concluded very soundly that pipe smokers in particular actually live longer than non-smokers! Yet in spite of the evidence that those who smoke without inhaling are generally no worse off for their habit than non-smokers (or are only slightly increasing their risks of grave maladies), this has not been reflected one iota in the public health policies surrounding the matter. In fact — pipe tobacco has recently doubled in price in my home state of New York, to the benefit of no one at all, excepting the tax man.

One could make similar remarks about chewing tobacco. For not all forms of this vice are equal in the eyes of renowned doctors and medical researchers. While traditional American chewing tobacco — the ‘Beech Nut,’ ‘Red Man,’ and ‘Day’s ‘O Work’ varieties — is indeed a malignant habit, with a demonstrated record of ravaging the mouth with all manner of mouth cancer, sores, and tooth loss, and indeed while the same can be said about fine-cut moist ‘dipping’ snuff that is placed in the lip — other types of oral tobacco usage have been proven to be essentially harmless. This is because the driving force behind the cancerous impacts of tobacco use boils down to whether the tobacco has even been exposed to fire. And while classic chewing tobacco and ‘dip’ style tobacco are both fire cured during their manufacturing processes — Swedish ‘snus’ is instead pasteurized, and never exposed to fire or smoke at any point in its production.

Swedish researchers have, perhaps not unsurprisingly, found that their ‘snus’ is about as carcinogenic as dark-roast coffee or smoked meat. The incidence of serious chronic illness among Swedes with a penchant for snus is barely higher than that of non-snusers. Yet in the United States, where Pietistic mentalities surrounding tobacco reign un-checked, these products are treated as every bit as much of a blight as Copenhagen dip and Red Man ‘chaw.’ Of course, given the research, if our public health officials cared about health itself rather than the Puritan-style outward appearance of purity — one might think these products would even be encouraged as alternatives to dipping and smoking. Instead, they are taxed heavily, hidden behind counters, and their flavored varieties are even banned in many cities and states.

Unless the extensive and thorough research done by the Swedish government is a shameful series of lies — which is dubious to imagine in a nation with a costly socialized medicine program — we can conclude that these taxes and bans are not driven by health at all, but by Pietistic morality and nothing more.

And so it is that I am a defender of snus, and of its older, more primitive grandfather — the tobacco pipe.

Of what import are these reflections as I seek to meditate upon America, traveling as I am across this wild land? To me, this essay is not about tobacco at all — not really. It is instead one example of many in a centuries-long battle between two chief factions within the American social landscape: the Pietists and the Liturgicals, the teetotalers and the beer-drinkers, the spreadsheet-thumping bureaucrats and the parochial romantics. However each of these might be termed could change depending on the subject at hand, but without any question in my mind, I would argue that they each cohere as competing ‘wings’ of American culture.

Far from being a defense of boorish libertinism and nothing more, what I wish to communicate in highlighting this difference is to suggest that G.K Chesterton was not wrong when he said: “Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.” This mentality, though expressed here by an Englishman, also speaks to something that makes America what it is.

For while the Pietistic progressivism of former eras gave birth to a gamut of joyless bureaucracies and to the fungible, interchangeable, globally-legible and metric-based wizardry of “progress,” the real McCoy in American life has always been found in the intuitional side of life. One could tear down the practice of drinking liquor or “throwing a lipper in,” one could cite any number of statistics about the inefficiencies of cattle ranching or the hazards of firearm ownership — one could rail against good barbeque or neon lights or barefoot home-schooled children. But they would do so in vain — for however well-meaning their ideals might be, they would spit in the face of the natural man and his land; they would denature the organic and wild and free, favoring instead the mechanical and the sober and the sensible.

In a country built by cider-swilling squatters and pipe-puffing provincials, the efforts of the reformers have only resulted in chaos. To illegalize the pig roast and to sanction the owners of tarpaper shacks; to legislate the labels on the tins of tobacco purchased by free-born Americans — to demand that taverns place the “NO SMOKING WITHIN 50 FEET OF ENTRANCE” signs on their doors; this is a non sequitur here in America, and I suspect the Pietists who remain here in this country know it in their hearts. Their fever for purity only increases the more they realize it — such is the psychology of overcompensation for what one has misjudged.

Left unchecked, their efforts will convert what remains of the free portions of this country into a gigantic HOA, complete with armed truancy officers and monitoring devices shackled to every teenager and toddler; a country where one must get a permit just to sit on his own porch. A vegan, teetotaling country where even the musket on the wall has been seized by robo-cops and botoxed federal agents — a nation where a man can’t take a pinch of a strong, spicy plant off the surface of the green earth to smoke to his contentment under the hickories, raising his eyes upward to heavenly God.

If we go that route — I’ll be hiding out in the swamp. And I’ll be praying that it won’t last forever.

Love it! I won a corn cob pipe at a carnival when I was 12. Still enjoy one good cigar a week. I love your demolition job on vile cigarettes. I’ve always hated everything about them. But you said far better than I ever had.

pressure is on... i haven't set aside the time to read much in months, so i am catching up using the audio versions