"Freedom only exists during the fight for it. The moment it’s won, the slow but steady creep of bureaucracy begins to destroy it."1

Like milk, freedom is a thing that seems to rot quickly on the shelf. Fight for it and it tastes like heaven — drown in it and and the spirit of man quickly darkens and dies. Those to whom it is bequeathed seldom recognize its blessing; nations that attempt to store it watch it putrify in the bottle but still sell it as if it were fresh. One bathes in it on the dawn of victory after years of battle, showering in it, ecstatic, like victorious racecar drivers and war heroes and great admirals after the hard fight has been won. But almost as soon as one has dried off and sobered up after the great success of revolution — the demon of restlessness smolders under the skin like a cautery from within, and nostalgic visions of the heavenly fever of battle-for-freedom fly through the mind.

Meanwhile, the offices bustle with tepid creatures who type and mumble and legislate the peaceful freedom for which so much blood was spilled. They’ve not wandered amid so many landmines in the miserable thickets; they’ve not tasted the blood nor dreamed this dream nor fought for it — it has merely fallen into their laps. If they are grateful, their gratefulness only flits across the surface of their mind as a triviality or a truism and in a single generation wanes entirely. Some, perhaps, are not grateful at all, but roiled in the domestic dramas of an obscenely comfortable era. The veteran watches, disillusioned at the fruits of his “fight for freedom” — wondering why the vision of victory seemed so much sweeter in the trenches than in its actual and living fact.

For on the battlefield, there were not traffic tickets and ordinances and permits, nor did the elaborate dramas of the terminally comfortable and bored ever factor into one’s decisions — for there were no such dramas there. One did not wait in traffic for a pointless romp with softheaded jackals during the war; city officials did not come to measure the height of your grass. Man was measured only by his capacity to rise to the occasion; by his commitment to the vision that unified all who fought — the vision of Freedom.

That vision could consist of a freedom from taxes or aristocrats or kings, or —the freedom to impose Sharia law, as in the case of the Taliban.

Here, I am not writing about any war in particular at all, but an ancient war that stands on as the thread tying all warfare together. For all war has an objective that is held in the minds of those fighting it as being benevolent or ideal. No man fights a war in which he believes victory would leave him worse off, not unless he is forced — in which case, there is someone far above his paygrade who sincerely believes that even the drafted man will be better off for his fighting. Some vision stands in the minds of the architects of human warfare of every age — a vision of something better, and because I am an American, I will call that “something better” by its most familiar name in my country: Freedom.

Indeed, many have “fought” for “something better” far outside the confines of martial conflict and literal war. There have been many who have fought for a piece of frontiers far from the stultifying hand of civil society, and there have been men who have devoted their lives to innovating some means for mankind to be freed from labor. One could even fight for freedom from the body itself, as in the case of the “transhumanists.” Inventors and visionaries, optimizers and settlers and pilgrims — all striving and sacrificing for some vision beyond their starting point; a place or era in which things would be better, and indeed, more free in one regard or another.

But perhaps freedom is only a Trojan Horse in which a force much worse than tyranny travels. For the one who labors under tyrants knows who they are and what they aim to extract from him. He knows that they are external to him, that they are alive in this earthly plain. In battling tyrants, he battles no demons save those within the flesh of his mortal enemies. If he should succeed in his fight, however, his war will not really end, though it may be called “peace.” He will begin to do war with himself.

And so it is that those who fight for freedom find themselves in the land of the Noonday Demon — known also as the mortal sin of sloth, or acedia.

It should hardly be a question in the minds of anyone now living in the developed countries whether ennui reigns and takes a toll on the spirits of virtually all alive today. Ours is an era of almost supernatural plenty and comfort — convenience stands among the greatest and most profitable commodities in our economies; and comfort has been boiled down to a strange and incredibly effective science. Salt, sugar, fat, gasoline, air conditioning, digital user experience — all of them are lubricated to such a degree that a man can live almost completely without thought. Ours is a world where one need only click, swipe, or push buttons in order to make their living, travel across town, or purchase virtually anything they might wish to consume or possess.

And yet, though this world of ours might be dismissed as a divine and joyous hallucination by the vast majority of human beings who have ever lived in any era but our own, it has not seemed to provoke a renaissance of beauty or spiritual gifts or human thriving.

I remember as a boy in Social Studies class, hearing the old argument that art emerged during the Neolithic Revolution — that the storage of grain-based crops allowed for a subset of human beings to have enough free time to produce art. The implication was as simple as it was absurd — that if human beings are given free time, they will make art. I remember thinking then that if this were really true, in our time — an era where labor-saving devices abound to fulfill an almost comedic level of basic human activities for us — that we should be living in an era of incredible artistic vigor.

It was obvious that we were not, and since then, the situation does not seem to have improved at all.

But the secular world has only the faintest explanation for why this might be. Some might make the outright ridiculous claim that ours is indeed an era of great artistic flourishing and human thriving — but such a claim would be patently unbelievable. “Deaths of despair” rise every time numbers on such matters are collected, and functions that anthropologists might consider to be essential to human community — like friendship, social activity, and mutual aid — seem to have been ‘optimized’ into oblivion. Other secular people would argue that these grim developments are certainly happening — but that they have come about owing to a “mental health crisis” caused by “chemical imbalances” in the brains of hundreds of millions of human beings.

For this, there are “happy pills.”

The track record of pharmaceutical mental health interventions does not lead me to believe that the human species has simply been waiting hundreds of thousands of years for the perfect pill, however. And the massive uptick in people seeing therapists does not strike me as a tempest either. In fact, a large number of those I’ve ever known to use these various means of alleviating the “first world problem” of despondency and passionlessness seem to report that none of them helped very much at all — and in many cases, they exacerbated the problem, sometimes fatally.

Perhaps the materialist-rationalist conception of being is lackluster at best — and actually diabolical at worst. The notion that man is a soulless, machinelike creature whose drives and hopes all boil down to the evolutionary biochemistry of the brain strikes as a macabre and degrading fantasy — it is a grim nightmare that the Priest can be replaced with the technician.

After many years of being a fervent anarchist, constantly obsessed with the idea of maximizing human freedom — while equally obsessed with the problem of the incredible psychological suffering coextensive with techno-industrial civilization — I became exhausted by the contradictions in my own thinking. It became abundantly, painfully clear that I did not possess the tools to diagnose and treat these problems on my own.

It was in that state of despondency that I sought some other wisdom — a faunt of wisdom that reached well behind our own era and into the ancient past. I found the heuristic of sin to be of incredible value, and shortly after, reverted to the Roman Catholicism of my youth. I found myself eating ‘humble pie’ mere years after dismissing the canon of Western Christendom as a milennia-long exercise in childish superstition — for the wisdom of the Church’s deposit of faith seemed to prove capable of directly addressing my concerns regarding freedom and human suffering.

Acedia, more commonly known as sloth and termed by the third-century monastic Evagrius Ponticius as “The Noonday Demon” can be translated from the Greek “ἀκηδία” as “lack of care.” This is not merely “sloth” in the colloquial sense — as in simple laziness — but the torpor of the passionless; a restlessness of spirit, boredom, ennui, discouragement, apathy, despondency. When a human soul slips into the languorous chambers of hopeless luxury and well-fed dread, he is slothful — and indeed, he is mortally sinning.

While “sin” is a word that most secular people find rather harrowing and unnerving, the Catholic understanding of sin is, taken in its most holistic sense, a transgression of the will of God — who is defined in the Book of John as love itself. His infinite mercy breathed each of us into life in a unique and singular manner, and He crafted each of us for a beautiful and benevolent purpose, Sin, then, is to defy His gorgeous and nourishing will for us, and in so doing, to separate us from Him, hurt ourselves and others, and to point our own lives toward ultimate and permanent defeat, emptiness, despondency, and death. I might posit that the sin of acedia, then, can be understood as a hopeless acceptance of the emptiness and defeat of sin and death — it is a current of thought in the spirit of man that waves away effort and hope; for in some sense, effort and hope flow from the same spring — which is God’s alone.

Far from saying that this grim condition is only a “chemical imbalance” that can be “corrected” with modern pharmaceuticals — the Church recognizes that the only salve for this condition is effort. Work and prayer, coupled with remembrance of death, tears of gratitude for the gift of life, and intense perseverance are the only correcting measures a human being can take that may aid him in unmooring him from the dark eddy of this grave sin.

Yet effort is the very thing our revolutionaries in the technosphere have sought to “liberate” us from. Freedom-fighters delivered us from various tyrannies, and commerical magnates crafted for us an “American Dream” — a devotional article in the worship of freedom and plenty. Work, effort, perseverance, and the memory of death seem to be the precise things which our world shelters us from and exhorts us to evade above all, and for it, we are now living in a time of profound and radical sloth. We are “Acedians,” living in the Land of the Noonday Demon — a ghastly fate none of those who ever fought for our freedom seemed to ever see coming. They seemed not to have had the faintest clue that in fighting for “freedom,” they fought only for the freedom to descend into the sin of sloth.

Of course, the human impulse to “fight for freedom” is not entirely stupid and worthless — it is only by and large misplaced. For there is no earthly freedom in this mortal coil; in spite of the babbling of idealists and utopians, (and I do say babbling, for I was one myself) we cannot create heaven on this earth. Our only thread of heaven in this life is that of love. And directly, without any reservations, I would affirm that sin is the antonym of love. Therefore, inasmuch as the urge to “fight for freedom” is situated as a fight against sin, it is the only sort of “fight” that any human being can engage in that may actually have the effect of creating a better, freer world. For there is no freedom worth anything at all if a man is still a slave to sin.

Where other struggles for freedom — freedom from political tyranny (be it in the form of frontier-settling or in revolutionary warfare) as well as freedom from exertion as found in technological development and 'optimization' — ultimately create a vacuum in which acedia reigns again, the struggle for freedom from sin does not and cannot do this except by human fault. The identification of acedia as a sin means that one must also struggle for freedom against it as well — other forms of "freedom fighting" lack this recognition, and therefore, their weakness is found there.

Such a battle is a lifelong battle in which victory comes only through Christ — and we cannot be certain that we have conformed to His will for us for all of the days of our lives. Therefore, there is not tangible and definite moment of victory, and as a result, no subsequent replacement with the freedom that victory has purchased. In this respect, the battle against sin is the most complete battle for freedom possible — and all others are paltry and ultimately of no value by contrast.

Acedia is intimately connected with a lack of exertion, or with circumstances where a man need not take care or maintain a vigilant disposition toward the life of his own soul. The one who cooks his dinner on the stove must pay attention; he must be creative, he must not let the flame of the stove burn his apron, nor can he allow the meal to burn. His mind is focused, and for it, the fruits of his effort are the fruits of earthly joy, even when they are simple. By contrast, the one who makes a meal of fast food is in the realm of convenience and ease; he thinks of nothing, mumbling his order into the microphone and swiping his card. He gobbles in his automobile, and when he is sated, he is sated in body only — the meal has not stimulated his soul, for it has come too easily.

And so, in the world of convenience, anomie reigns, and sloth bites at the spirit of a man. He is in a realm of incongruity — everything is "all right," at least by the most basic metric, and yet, he is lacking something ineffable that he cannot name, and because of its namelessness, his instinct says to ignore it. But ignoring it only feeds it, worsening it, until over time a man is rendered totally despondent. The longer a man lives in the world of easy things, the more drastic his descent into the hands of sloth — the Noonday Demon.

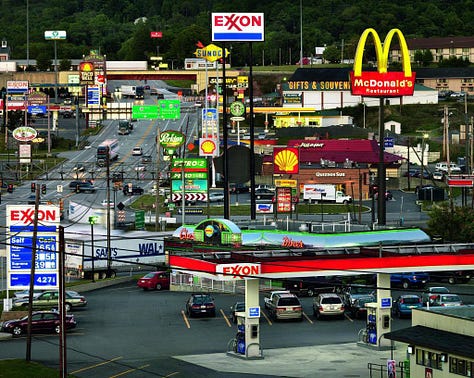

Is it any wonder, then, that the relative density of commercial development in a given place is a fair metric for the authenticity of culture? By this I mean, within the sprawling gigaplex of strip malls and interstates, one finds only the dimmest and most ersatz copy of American culture, and indeed, of the human spirit. A sickness reigns there, one that is not nearly as present on our dirt roads, or, say, on roadless islands which can only be accessed by boat. Even our county highways and dusty rural routes are not afflicted as badly as the "Breezewood, Pennsylvania" commercial zones.

Though it could not be posited that 'effort' is the diametric opposite of sloth, not really — God is the true opposite of sloth —- this formulation is not without at least some merit. For the spiritual void created by convenience and ease lessens as one departs into territory where life requires greater effort. It should not be any wonder, I should think, that there are now so many youth who have ambitions of "homesteading," and so many "urban refugees" who are striking out in search of the country life. Their efforts appear to be an ambling, half-conscious response to the problems posed by the mortal sin of sloth. And, it should be mentioned — for every handful of Americans who aim to "go back to the land" in one form or another, there are at least a couple who are finding themselves walking back into Churches as well. Theirs is another response to the problem of Acedia — a response that is, to my mind, far more complete.

To understand these developments, one must take a brief look at the history of the United States. We are a nation whose birth was revolutionary in character — our founders were guerilla warriors who sought political freedom and did so by bloodshed. The impulse for "fighting for our freedom," then, is ingrained in the national character of the American people. But like most fights for freedom, no recognition was written into it which would identify the problem posed by sloth; and so it was, as the man on Twitter said to me yesterday, in so many words, "freedom found only in the fight for it, a freedom rapidly consumed by the peace that followed the fight for it."

Quickly, the "freedom-fighting" impulse found another outlet: The frontier. As the slothfulness of peacetime bureaucracy took root in the old East, our "fighting stock" men struck out to the Western lands to do battle with the elements and to conquer Indian lands for the sake of the country. Rather than quelling the spirits of the American people, this development only channeled energy that once went into shooting Redcoats into shooting Redskins, and later in founding towns, panning gold, and building dams. But not all who adopted the "frontier mentality" were actual settlers in Western lands — for many others back in the East, this same mentality was applied to commerce, which became for many a sort of facsimile of war. The early tendrils of "The American Dream" rose to the surface of our people as the ultimate vision of "freedom," and they fought to achieve it by founding companies, working in factories, and scheming up tycoonish ambitions that would someday purchase for them immense freedom.

In both cases, these efforts only purchased further miring in acedia, for again, neither the frontiersman's rifle nor the capitalist's tenacity provided any schema for what a man might do once he aquired his vision of freedom. And so the American people wandered into the twentieth century. Throughout this time, various wars also piqued the old literal "freedom-fighting" urge in men, and when their efforts were settled in so much blood, they found themselves again wending into the world of frontier-settling or commercialism. In these regards, the American story is, in truth, one vast patchwork quilt of various iterations of "freedom fighting". But none of the substance of these fights contained any signpost toward solving the underlying problem of sloth.

Later, innovation became a sort of "freedom fight" itself — the fight for human freedom from effort. The iron law of history that man must live by the sweat of his brow could be trounced by the genius of inventors; it could later be refined by increasingly idealistic and even utopian optimizers. If only we could do away with the rough labors of farming life, and later the morbid darknesses of factory work; if only we could live in a world where all of the desires of man could be sated with the push of a button, the swipe of a card, or the flicking of a switch — and where we cannot actually reduce the effort required, we can at least export it. And so it was that a nation supported by neoliberal economic policies rose, where factories were sent overseas, and a nationwide frenzy of office work began. Automobiles, drive-thrus, fast food, cell towers, telephones, and televisions flourished.

The innovator was the clean, neat, idealistic visionary whose "fight" for the nebulous freedom from work yielded enormous economic output and the development of the world's most complex and impressive technologies at a feverish pace. Electricity came to far-flung locales as a triumph; later the radio came, automobiles and lightbulbs and washing-machines, computers and surveillance cameras, and even later — the internet, that ultimate handmaiden of acedia.

Even the Taliban commented on the internet after the fatha — their victory over Afghanistan, when US Forces pulled out of Kabul in a whimper heard around the world. “I spend most of my time on Twitter … Many mujahedin, including me, are addicted to the internet, especially Twitter,” one said. “If we complain, or don’t come to work, or disobey the rules, they cut our salary,” said another. Some even stated that they missed the days of Jihad; and so it was that in one fell swoop, in only ten months' time, these freedom-fighting Jihadis made an unwitting indictment of the history of the developed world.

It is said that "history repeats itself," and I suppose there is no clearer instance of this than what is found in political discourse today, where an expression of political apathy is often answered with admonishments to "fight" for "our freedoms." But whatever this "fighting" looks like remains obscure — for violence, the ancient heart of any kind of a "fight," is strictly illicit, and most people seem to be trapped in such a comfortable quagmire of sloth that any murmurings of revolution strike as being totally absurd. As one friend has remarked, "as long as the AC keeps running and the price of beef stays low enough to allow for frequent barbeques, there will be no civil war in America."

Even for those who reject such a theory, it is clear that in spite of the extreme political division now thriving in the United States — no one wants to be the one to fire the first shots of any revolution, for the possibility of prison is not only real but extremely likely for any would-be American guerilla. And if, then, the "fight" is to be waged at the ballot-box, it is clear to see that even if our votes are counted honestly (an idea that is contentious among many) that the surgical level of narrative control that the Powers That Be seem capable of in the news media is almost insurmountable to contend with — unless you are exceedingly wealthy.

What, then, could those now proclaiming the need to "fight for our freedoms" really mean? Do they mean we should fight in the cultural domain? Do they hope for us to hold signs in "free speech zones" at protests? Are we to be writing novels and painting paintings that might influence the culture so thoroughly that we are later able to secure some sort of a dubious and far-fetched political victory? Are they suggesting anything at all? Or does the fantasy of "freedom fighting" simply linger deep within the collective psyche in an era when technological development is no longer viewed as a necessary and glorious triumph, when the frontiers are totally settled and closed, and when our citizens are even growing tired of the endless march of "optimization?" What are the fruits of such an impulse when it not only lacks any apparently suitable outlet — but when virtually all of us are residing in easy places, flooded with conveniences, and languishing in a nationwide eddy of anomie and acedia?

There can be no suitable answer, insofar as I can tell, save whatever is yielded by a serious and nationwide meditation on both acedia, which I have meditated upon at length here, and freedom.

I still appear to value earthly freedom. Do I really care for "freedom" in the most commonly used sense of the word? Perhaps I do not.

Perhaps what I am after is only liberty from a fickle current of novelties, from the ghastly hand of commerce and the weightless grin of the "re-educators" with their perversions and needles and pills and charts. Beyond freedom from sin — an effort at which I am certain I shall work all the years of my life — I simply want a slice of the earth where things are reasonable and decent; a world of whole and romantic, uncut, unfiltered, bleeding, real things.

Whether these things exist under the thumb of a tyrant somewhere is of no concern to me, at least not in theory — for I can tolerate tyranny if it is a faraway thing. It is only the niggling, granular, tiny tyrannies that drive me mad — and they are all the worse for ever traveling under the disingenuous banner of "justice" and "democracy" and so forth.

A forest that will not be cut down and turned into trinkets; a gaggle of girls who will not be mangled by surgeons or addicted to fentanyl. A boat that a man built and drives around the bay as he likes, no inspections or oversight but that of his own invention and drive. Nothing of this is "political freedom" at all, not really. It is only wholeness, slow-moving, taken straight. A wholeness that allows the human being to be a human being and assumes that he has lack of freedom enough in the internal tyranny of his own sin — and that no official or inspector would be so indecorous as to add to that burden.

No, I do not want the screaming, flag-waving, shot-firing exhilaration of "freedom," I want the stasis of God's good earth, living and green, untrammeled and unpaved. I wish for a corner of it that could be kept and stewarded by humble, fallible souls, where our children can live and climb the maples and jump into the creeks.

This does not require war; it only requires that one prayerfully march off into some hardscrabble patch of woods, well off the beaten path and well beyond the sight of Godless buzzards who gnaw and buzz upon a happy man like a fly upon meat. Forgive me if I am on a quest to find my little patch where I may ever be able to live in such a manner — I do not think the ballot-box, the television, or any amount of money in the world could buy it for me.

The place where I will find the wholeness I seek is known only to God, and it is apparently my mantle to broadcast my journey towards it publicly on this website. I will find it — I'm only as close to finding it as I am close to blowing the sin of sloth out of my veins forever.

I will find it in the hinterlands, God-willing, far from the convenience stores and drive-thrus and even the paved roads — as far from the Land of the Noonday Demon as I can get.