Last of a Dying Breed

The Yokel's Remedy for a Homesick Age

I am profoundly sick. But I do not have a cough or a fever, nor stomach pain nor septic wound nor toothache. Pneumonia and flu, cold and runny nose: I do not have the slightest touch of any of these, and yet I am gravely sick. If I am now mentally ill, one could not call it "depression" or "anxiety," and so far as I can tell, no doctor could diagnose me with schizophrenia either.

Yet I am very seriously sick, and unfortunately, the only hospital that could help me is exactly 2,058.7 miles away from where I am typing now.

I am, for the first time in my life — homesick.

Homesickness is not a condition that is often discussed among grown men, and among the sorts of men who often travel long and far, it is usually very conspiculously never mentioned. In my case, I am especially resistant to making any admission to suffering from it, given my public-facing modus and lifelong resume as a vagabond. I hesitate to even publish this article, in fact — especially the very week that Hickman's Hinterlands has pulled into the Top Ten in Substack's "Travel" leaderboard, and as we begin our ninth straight month of full-time, continuous travel under the banner of our Falling Back in Love with America project.

Yet I have no choice but to admit it. I know my sickness is so gravely serious that I would do my readers a profound disservice by concealing it. More to the point — I could no longer hide it even if I tried.

My symptoms are like this: In attempting to write, I am paralyzed. In attempting to sleep, it is as if I am fasting from rest, tossing and turning red-eyed. At dinner, I am never hungry; the beef feels limp and even good wine tastes like acid. Irritable and distant, distracted and inconsolable, my heart is weighed down by a deep yearning for the hills of my Eastern home — which I only left a month ago. Because of these ailments, I am suffering from a complete drought of focus, and as various projects and obligations mount, my despondency further increases. This is all quite serious; it is not a bit or a literary stunt I am performing here for the reader — this is instead an honest account of the sad truth of my present position.

Even more frustrating is the intense embarassment these feelings cause me. It is as if I have softened totally or been caught in a ridiculous bluff. Like the nine-year-old on his first trip to summer camp, I — Mr. Traveler, age 30 — beg the counselors to allow me a tearful telephone call home to mother. And I weep, begging her to come and get me. My tough facade as a swashbuckling King of the Road has melted. The mandate I’ve received from you all to set out across America to gather electrifying tales from her heartlands and backwaters slips from my hands.1 And after a lifetime of devoting myself to the act of pure travel for traveling’s sake — I watch the sum total of that great effort evaporate as I gaze at photographs of home.

Something is changing in me. I feel quite hopeless to stave it off or arrest it — I now yearn for the porch and the daily walk; for a seat at the village tavern with my name on it and for long evenings by the woodstove. God-willing, I will return soon to embark on a totally new chapter of my life, with my wife at my side in our northern home.

For now, I must continue on my path. Thankfully, I have extensive notes and photographs from these nine months of traveling that, because of the harrying nature of the travel itself, I have not yet had a real opportunity to process into articles for Hickman’s Hinterlands. Perhaps sometime soon, I’ll get a long, unbroken fortnight of fortnights by the woodstove to do exactly that. With any luck, I’ll be pecking those essays out on my own porch again instead of at yet another Motel 6.

If I have learned anything at all from these months of continuous travel, or from any of our efforts at “Falling Back in Love With America,” it’s that I have no need to fall in love with every inch of this country. Far from it — such a thing would not be possible no matter how hard I try. Our nation is changing constantly and quickly, and above all — it is simply too vast in size.

But even if America’s vastness can be conquered by means of planes, trains, and automobiles, the great bulk of what anyone will find in passing along the surface of the North American continent will be disturbingly similar. At the risk of sounding totally cynical, I can only describe what goes on in the vast majority of this country as a human monoculture. Our towns, cities, highways, and villages are mired in a purely commercial, globally fungible approximation of a human culture that is, at bottom, the anthropological equivalent of a cornfield. In so much of America, climate, flora, and signs for regional corporate chain businesses are the only indicators that one is in one place and not the other.

If an alien were to tour the United States and provide a brief summary for his commander, he might say something like this:

“Long asphalt paths connect the towns, on which the humans drive rolling machines from one to the next. In general, these towns consist of a series of long ‘strips’ with 5-lane, 45-mph roads flanked by glowing, box-shaped buildings in which commerce is conducted. The humans purchase 100% of what they consume from these buildings. Behind those buildings, there are many smaller roads where vinyl-clad living structures are. Inside those structures, the humans seem mostly to look at bright screens and occasionally sleep. Nearby, there is usually a “downtown,” where a minority of residents live and those in the vinyl-clad domiciles only occasionally go. Note that there are “rural” towns as well — usually an asphalt path surrounded by houses and calorie-production facilities, with a “Dollar General” nearby. And in “urban” areas, there are streets with smaller glowing buildings for commerce, on narrower streets, and most residents live either in “apartments” or in more average-sized towns outside of the city. While climatic differences distinguish each place, and the humans assign values to them within their caste system, they are otherwise usually indistinguishable.”

After continuously traveling the United States for as long as I have, I could not argue with the alien’s rather dismal description of my country. That is, I could not argue except for one thing — there still are towns and people who are, often by their own admission, “the last of a dying breed.” For the art of really traveling the United States is the art of somehow finding a backdoor out of the monoculture — which is, more and more, far easier said than done. To truly understand what this country could be, and in some places still is, one must venture to the places that are off the highway, out of cellular service, and far from the places where “economic development” is a going concern. Finding these types of areas is simply not a thing you can Google — because if it’s on the internet, it’s already been “found.”

In such places, one is liable to meet men who still do not own a mobile telephone. Some have never filed a tax return. Their wives may be old crones who pride themselves on how they hardly ever go to a grocery store, and their old-timey regional patois may be borderline incoherent to outsiders. There are still places where, as the Steve Earle Band said in their hit song Copperhead Road, an old man might really “only go to town about twice a year” — and his family may still largely subsist on what they kill, grow, and make from the land around them.

When I have had the great privilege of being in the company of such men, and have gotten the rare opportunity to survey the isolated hamlets in which they reside, I’ve been struck by a profound sense of what so much of America has lost. Or, worst than lost — in many cases they’ve eagerly given it up. I’ve also gotten the tragic, sneaking sense that such places and their people are a critically-endangered species.

What makes such places what they are is their profound, almost alien fixity. The residents of isolated, back-woods locations are often so distinctively “American” in an old-world sort of way simply because they do not interface with the outside world very much. If there is anything I have learned, it is that connection to the outside world is — indisputably — a harsh, fast-acting cultural corrosive. There are a few chief ways in which this corrosive can enter the bloodstream of a still-old-timey sort of place:

Good roads

Commerce

Tourism

Government (schools, programs, initiatives, etc.)

Communications technology

Gentrification

Each of these involves the movement of people, money, and ideas into an area — and those corridors of motion are well-established. Each time a community is newly connected to these channels, they seem to find that these new roads aren’t two-way streets in the manner they might’ve hoped. What they give to the outside world is not their culture — it is their land, their money, and, if the tourists have come, a cartoonish simulacrum of their culture. What they receive are cheap products, bad traffic, trash at swimming holes, and the bad, often perverted ideas, practices, and politics that now circulate so widely on America’s “Main Street.”

Now, many could read that list and say — “wait a minute, those are all GOOD things that people WANT!” And in some regard, they’d be right. The history of rural America has, at least in some parts, been characterized by an ardent desire for modernization — for roads and electricity, for jobs and tourism and, lately, a dubious crusade for rural broadband internet.

In due time, however, whatever our rural modernizers might’ve hoped for in the arrival of a newly-paved road, a cellular tower, rural broadband, “jobs,” or increased tourism proves to have been a dirty trick. Their children eat Oreos from Dollar General instead of black-caps from out by the crick; they listen to Justin Bieber instead of singing hymns on Sunday. They tell you they’re going to move to New York City when they grow up, and the neighbor’s son won’t trap beaver anymore — and he says he’s a girl now. Meanwhile, out-of-towners are buying up the houses left and right — and they’re bringing their wacky politics to the town board — and they’re on the internet telling all their friends they ought to move here, too. It’s a spectrum, of course — some towns get it worse than others, but almost everywhere is now impacted by these changes in some regard or other.

A man who sees these changes sweep through the seldom-seen village of his youth might feel sick at the changes he’s witnessed. He might be enraged or depressed. He might adjust even if he knows what he loved has changed so drastically, or he might move off, deeper into the woods or to another state entirely. But there’s hardly anything he can do to save his place and its unique way of life — by then, it’s just simply too late.

He, like me here in this motel way out West — he’s got a bad case of motion sickness. Though he may never have left his humble town, he might be homesick right on his own front porch: because where he’s living now, he’s never seen it before. He might as well have moved to a foreign country — or, perhaps a foreign country moved to him. But the problem is, that foreign country is now almost all of America. The very monoculture I so bitterly lament now steamrolls so many of this country’s crown jewels, even now as I write this. In just ten years’ time, I’ve watched it happen myself to a long list of places I’ve loved.

And as goes some of the other places I love so dearly, I get the sad sinking feeling that now it’s just a matter of time until they’re pulled into the monoculture, too.

As I sit here and stare out at the neon-lit stretch of desert before me, I reflect on my sudden and confusing ache for home. It’s a real conundrum to me. To have finally ‘made it’ as a man who is paid to travel and to write; to be living a childhood dream by the good graces of those who like to read what I’ve got to say — but to be caught in a ghastly rut, disillusioned, exhausted by the long, long road my wife and I have been running, even struggling to write. Just last night, I wandered over the railroad bridge with my Rosary, fumbling the beads as the trains roared past, praying: “Lord, why now? Why do I have to be homesick now? What are you trying to tell me?”

I can’t know what He has in store for me, but I can say this: My experience being homesick here has led me to take a cold hard look at the sorry state so much of this country is now in. The 20th century had a fetish for motion; for commerce, for mechanized efficiency and speed — the Interstate System and the jet-plane, the radio tower and the telephone. That led to TikTok and PornHub and Facebook Reels and Youtube for babies, and, no doubt, even to Substack. The information travels at the speed of light now — when I hit “publish” in a little while, it’ll be in your inbox on your “smart” telephone in about five seconds. This is the world we’re living in, and the particular respect with which this all pairs with the American spirit is a thing we haven’t fully thought through just yet.

For what is an American if not a homesick sort of fellow, at least deep down in his heart of hearts? This is a nation that was not built by men who stayed home. Lewis and Clark weren’t home making cups of tea in fine China for momma — they went in a canoe down wild rivers, occasionally becoming convinced they might never see momma again. Our immigrants packed their trunks and boarded westbound ships, or wagon trains, or packet boats, or steam locomotives, knowing full well they’d never see the “old country” again. Sure — in an encampment of migrants and drifters, one must employ a certain degree of machismo to strong-arm their homesick feelings out of sight. But I’ve got no question in my mind that that feeling figures prominently in the “dark matter” of the American subconscious mind.

For such a people, then, to have later invented the most state-of-the-art motion technologies is a frightening concept. One imagines a wino drunkard in the age before distilling was discovered, taking that first tipple of extra-strong liquor from a primitive still — that is a dangerous moment. For the hapless European diaspora, cut adrift in the new world, to then dive headlong into the world of trains, planes, automobiles, television, and the internet sounds to me like a good recipe for a nation of desperadoes. Add money to the mix and you’ve got the sprawl around Denver, or the New Jersey Turnpike, or the gentrification of Bozeman. And if they aren’t barreling down the highway to the next city, they’re barreling down the “information superhighway” to whatever fantasy world they’ve constructed — forever, whatever the cost.

When it comes to culture itself, it does seem to me that the ones who produce it in the most original sense are the ones to whom fixity is no strange idea. To remain in place for all of one’s life; to “live a certain type of way,” even to hew to a parochial ideal about what one ought to do and not do — this is what men who produce culture do. The “open-minded” and infinitely mobile; the relativists and universalists — they seem not to produce culture worthy of the name but only to consume it. For they have no zeal for absolutes, nor are they married to oak trees or stones or spawning salmon. They are not fiery-eyed in their fever for God or their hard-won acreage, nor stubborn on the question of a life best lived. They remain in motion — always in motion — grazing upon this and that as they go, wandering into the movies, absconding from their towns and Churches, “making it up as they go,” but indeed, leaving what they have made behind on their aimless path as they go.

Even their ‘culture-makers’ only pluck various authentic characters from wherever they still grow, using them in novels and films and paintings. It seems they are getting harder and harder to find. But there will always be peasant villagers and hillbillies; even now, somewhere in Kentucky an old boatman smiles as his new cellphone flies overboard into the river, and somewhere in Idaho there is a man who’d rather pick huckleberries than ever get a job. And deep in Downeast Maine, a young lad stands on a wharf speaking his mysterious old brogue — “ayuh, we’ah gunna scoot da boat up‘ta Cutlah ‘ta see Auwnty Mawtha on Mahch Fust.”

He will, God-willing, never learn the King’s English, nor will his name ever reach the desk of any “human resources” department — or any IRS office — anywhere.

Though such types may be few in number, they are as Atlas to our nation, unwittingly carrying our whole world upon their backs. Without them, we lose the plot — we forget everything, and we shall find ourselves desperately trapped in a global “economic development zone” where, for all the word “diversity” may be bandied about — there’s simply none to be found anywhere. For in that world, they all wear jeans and Nike sneakers, with iPhones in their pockets, no matter where they came from. Living in their own sort of ‘nowhere,’ they seem to look to those who live in the ‘middle of nowhere’ for clues as to who they ever were or could still be.

As I write this, I remember that I am from the middle of nowhere. I’m from a place that Edmund Wilson described in this way:

“Unlike most old things in America, Upstate New York is an anachronism that still flourishes, that is still more or less of a going concern.”

That the word anachronism literally translates from its Greek roots to mean “against time” makes it such a perfectly fitting description of my home state’s far-flung rural regions — for our land and its people still somehow quietly defy the current of American Main Street and its tireless impulse for modernization at any cost.

For example, when I first watched my old Uncle Andy try to use a computer, at the age of sixty-two, he did not have the slightest idea of what he was doing. That the movement of the mouse correlated with the movement of the cursor on the screen confounded him. He pawed the plastic mouse with all the finesse of a gorilla, moaning tones of gruff irritation — until finally, he stood up and said “Bah! These are such ridiculous things. I just don’t know what the point of this stuff is.” To this day, he has my grandmother — his sister — send emails for him in the rare event he finds it necessary to send one.

Years before that, I have a fond memory of riding north on NY-28 with an old family friend, speeding by the giant stone cliffs north of Old Forge to get up to camp. The man at the wheel was a hill-country sort of fellow named Elwin; a soon-to-retire highway worker who was firmly set in his ways. He’d been gifted a mobile telephone recently, and as we sped up the road, it began to ring loudly. He was so startled he nearly swerved off the road. Enraged at the obscene beeping of that tiny machine, he dug it out of his pocket, rolled down his window, and summarily chucked it into the pond at the bottom of those giant stone cliffs, where it made a large splash.

“I don’t think I’m gonna like the future,” he said. “Seems like it’ll nothing but a bunch of damn beeping blinking plastic shit and foolish nonsense.”

Even to this day, I can’t say he was wrong.

These are men who can count the number of times they’ve left the Empire State on one hand; men who have never had a Passport in their lives. Often, many years of their lives have passed without their ever venturing beyond the county line. They are as rooted in the land here as snarling old hickories and beeches, and for it, they are true characters.

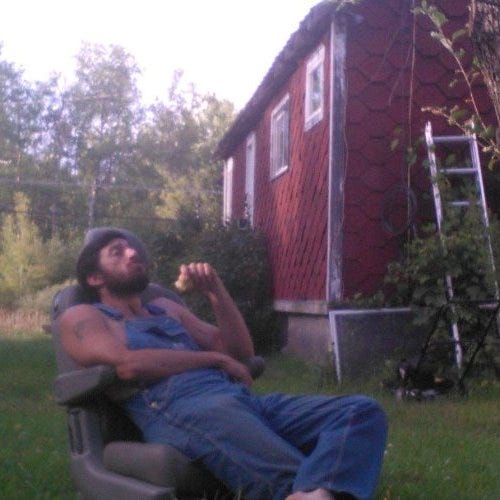

And if I am today ever called a “character” myself, as I occasionally am, I probably owe a great deal of whatever makes me one to them. After all, their weird old world is mine, too — it made me who I am, and it is mine to inherit. The anachronistic land of my youth has continued to run against the all-consuming monoculture, and it’s been doing so all my life without my help. How much firmer could our bulwarks against the monoculture be if I stood strong in my homeland, sans mobile telephone, car, or job, cackling along our muck-brown rivers and granite rock-walls and larch-flanked bogs? To chew the spruce gum and eat the roadkill beaver meat; to fire up the still and put a shotgun slug in my laptop — yes, I rather think I’d do my country a great service there, schlepping firewood around on a snow-sled, mumbling to myself as the trout line bobs above the ice, fixed in place and forever “behind the times.”

Just thinking of it brings a smile to my face. To see the look on the power company man’s face as he arrives to disconnect my house from the grid, and to sip whiskey from a deer’s hollow femur-bone as I bark at the coyotes. No, I couldn’t have started out like this — I was too hot to trot to see the whole country at first. But now that I’ve seen it, I know where I’d do best to be and to remain. Though “falling back in love with America” could’ve looked any number of ways, these months of meditation on the matter really only seem to teach me one thing — and that’s to go home, to stay there, and to pray the whole world doesn’t come stampeding in on the dirt roads and fiber optic cables. To be a modern-day villager or peasant, trotting up the tired old pinnacles of stone and mumbling my prayers; eating bowls of sprouted einkorn for breakfast with bush meat and black-cap berries — arriving to dinner parties by mule-cart and firing my flintlocks over the lake for the Fourth of July — that’s where I’ve got to be. That’s how I’ll love this country back into what she ought to be.

Just thinking of it eases the homesickness. For now, I’ve got another westbound train to catch. But it won’t be long until I’m back home again. This time — home to stay.

Though, I’ll emphasize, I have more than enough material already to complete the Falling Back in Love With America project. It is simply a matter of precious focus and time to actually write the numerous essays I have already outlined.