"He who travels to be amused, or to get somewhat which he does not carry, travels away from himself, and grows old even in youth among old things. In Thebes, in Palmyra, his will and mind have become as old and dilapidated as they. He carries ruins to ruins."

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self Reliance, 1841

“The biggest misfortune in human history is the invention of the combustion engine. Cars & aeroplanes diminish the world, rob it of all its diversity. Young men who meet me want to know how they could do what I've done. But all they can be is tourists now.”

Sir Wilfred Thesiger, interview with Washington Post, 1999

I recently watched a baby crawl onto a tall mattress and wobble at its summit. This baby — a Canadian child — bumbled about on the floor in a state of incredible bliss and fascination at the slightest minutiae, reveling in the variegation of the obstacles and objects on the floor; and the climbable height of the mattress posed a valiant challenge to her small form. First an arm thrown lackadaisically over the edge of the mattress; then a leg — and then, like a crab mounting a sandy bluff along a harrowing, storm-tossed beachhead, the infant found herself dazzled by the heights to which she’d traveled, high along the apex of the mattress.

Faced away from the kitchen, she seemed to forget it existed. The dog was behind her; mother was behind her, father in his chair and out of her sight — if studies of infants’ cognitive abilities are any guide, her summiting the mattress was, so far as she could tell, her own solitary endeavor. Object permanence does not develop in the human brain until much later — that critical quality of knowing that when one turns away from a tree or a doorway, or from mother and father, that they all nevertheless continue to exist.

Can one imagine, in total absence of any ‘object permanence,’ what adventures the child must have in her own living room? Or — the total exhilaration, often of the most terrifying variety, involved in turning her head away from mother and father? As her head turns, it appears they have disappeared forever — and she becomes a lone wolf in a world of curiosities and dangers. As she crept up the mattress, I watched her gaze appear to reflect the seriousness of the challenge before her; I watched her lackadaisical, infantile manner firm up into something akin to resolve — and it was a beautiful and incredibly human thing to observe.

But at the high summit of her fluffy mountain of bedding and springy mattress, she attempted the inconceiveable — she tried her hardest to stand. And for a moment, she seemed to believe that it could be done. Perhaps she had reason to believe that such a thing could be done, of course; long ago, back when her toddler sister was in view — back when her toddler sister existed in her mind — she had observed her doing similar things. She firmed up her knees, lifted her midsection — and promptly went tossing downward toward the cold, hard floor.

My hand flew to arrest her fall, as I was close by on the rocking-chair; and unfortunately, I had only time to break her fall by catching her head — or essentially by giving her a frightening whack to the face. While I wouldn’t have preferred to address her dire situation in this way, so far as I could tell, it was far better than allowing her to tumble headfirst onto the floor. Wounded, she wailed and wept, and her smiling father took her to comfort her. I nearly felt remorse, for her emotions were so strong. Looking back at me from her father’s lap, her eyes cried out to me a tale of betrayal as she wailed; her eyes said with great intensity that I had injured her pride and self-respect with my unreasonable blow to her face. Of course, I knew at the bottom of it that I had saved her a good deal more injury.

Rocking in the rocking-chair, I thought to myself — what adventure! For this little one, she is already a vagabond, conquering far-flung and foreign challenges here on the floor, experiencing the full spectrum of human emotion — the most sublime joys, hurtling through her tiny heart; and indeed, the deepest, bitterest sorrows and moments of incredulity and fear. In this regard, this beautiful little infant seemed to be nudging me to consider travel in another dimension entirely. She made me wonder whether one needs to go very far — or to go anywhere at all — to employ the traveler’s mode to good effect.

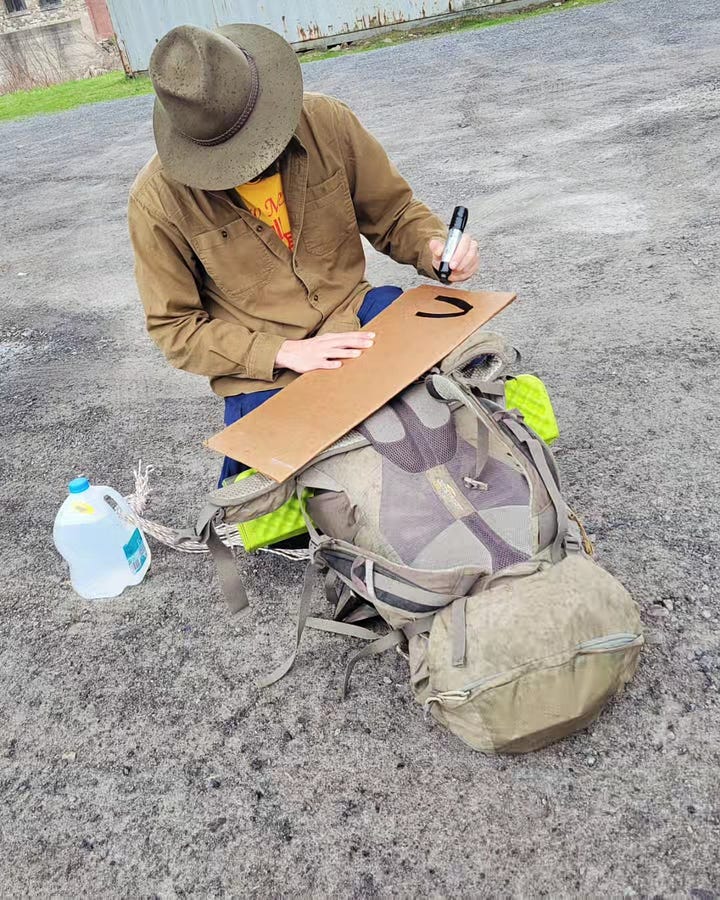

The red-headed boy from British Columbia drove 70mph up the I-25, while his grandmother — an old woman from Ohio who said “warsh” instead of “wash” — snored in the back seat. The sun had left Wyoming cold, and the mountain winds whipped across the blacktop in violent gusts that seemed insistent on pushing the SUV toward the white line of the shoulder.

“Nietzschean Christianity — how about that!” the young lad exclaimed. “No inherent meaning in anything but the experience of the self in the present — and where does that leave Crucifixion?”

We went on, barreling down the wind-lashed highway, delving into the heady territory of summer-break-from-college midnight discourses. I was a total greenhorn hitchhiker — raising my thumb still filled my belly with adrenaline every time. I had no idea that I’d keep doing what I was doing for so long; no clue that one day, I’d hitchhike the same road and feel nothing but vague boredom. Our conversation started like a campfire, and then a bonfire, and then a furnace — two young college-aged guys, feverishly babbling about meaning, and God, and sex with increasing fervence and blustering conversational force.

The weather began to mirror our conversation, but the red-headed Canadian lad didn’t notice. Soon the gusts sent glassy sheets of Wyoming rain against the windshield — like being carpet-bombed with splattering bullets of icewater — and the driver’s Chihuahua started to whine. We passed tractor-trailers as they did battle with the winds, we sped toward Casper in a nightmarish world of black rain, babbling and drinking coffee at midnight — until all our talk about God and the meaning of life was interrupted by blood-curdling shrieks issuing involuntarily from our own mouths — and the Chihuahua had pissed itself on my lap.

Only in retrospect do I realize how completely each motorist on the wild American highway places his life in the hands of road engineers. The types of men who Teutonically stare at spreadsheets displaying information about rates of drainage, the impact of so many lumens of streetlight pouring into the cornea, signs and lines and median reaction times — they shield us all from a world of constant death and emergency. One miscalculation from any of them spells accident after accident — and we’d found one blind-spot in the Wyoming Department of Transporation’s engineering department in an asphalt depression outside of Casper, Wyoming.

The rain had flooded the low spot beneath an overpass, and traveling at 70mph, our vehicle hydroplaned; spinning 180-degrees, flying backwards up a concrete retaining wall and snapping the rear axle. As we came to a stop — eyes closed, all certain we may have met death or horrifying injury — the SUV pitched downward into oncoming traffic. An eighteen-wheeler sped by within an inch of my window — and my eyes saw the pure white of certain death.

When I rubbed my hands against my leg, noticing the dog piss that had soaked my jeans, feeling myself for blood — heart still racing — I leapt out of the door into the hellish downpour and screamed a guttural, primordial yowl out in the passing lane — an instinctual celebratory exclamation of life. Miraculously, I wasn’t dead, and neither was anyone else.

Seconds later, a towtruck backed down the off-ramp and sped down to us. An exceptionally short, swarthy man hopped out of the truck, saying “My name is Elvis Lick, how do you do?” He proceeded to explain that he’s a first responder in Casper and that he was here to help us out. His kids were in the truck, and his wife tossed him a blanket through the window, which he promptly put over the old Ohioan woman — who was receiving quite a warsh from the ceaseless rain, and was quite shaken besides.

Later, we found there wasn’t a single motel room available in all of Casper — as the shale oil boom was on, and workers seemed to have taken up residence in every single available space. No matter — Elvis Lick offered us some floor space in his own room at the Motel 6, where he “had some family staying.” Upon entering the room, it appeared he didn’t just have “some family” with him — unless “some” meant his extended family. Fifteen or so people were crammed in that two-bed motel room, several dogs, babies, and big piles of luggage were all somehow made to fit. The combination of snoring and mammalian humidity hit me in a grim wave as I passed through the doorframe, and it was clear there was no room for me.

“I’ve got enough camping gear — I’ll sleep by the highway and catch up with you all in the morning,” was my answer to all of that, and Elvis gave a half-smile and bid me goodnight while my driver and his grandmother wedged themselves and the Chihuahua in between anyonymous, snoring silhouettes.

Later, I charged my cellphone in the motel lobby, where the television was on. The headline was that a family of five hyrdoplaned in the same spot we did, only an hour after us. One was declared dead on scene, and four others in critical condition, helicoptered to Cheyenne. Such was the fate we had only by Providence avoided.

I thought of this again as I watched the baby fall off the mattress. In many regards, life seems to be nothing more than a successive chain of such events; one scuffs their knee on the sidewalk as a boy and, such things being relative, feels every bit of the fear one later feels in an automotive brush with death. Every era of life seems to have its horrifying and sublime peaks, even from the beginning — summits we approach with great resolve, seeking ‘somewhat which we do not carry,’ as Emerson says; and when the tumbling fall comes, we are inconsolable and shaken stiff. In the moment of the tumble, one feels as helpless as an infant — but in tumbling again and again, one also ages, sometimes profoundly, into a pallid, ruined creature.

If wisdom comes, it is the only honey one finds in all of it, and for the traveler, it comes in oblique and un-digestible form quite often — it is the weird consolation prize for the successive layers of infantile helplessness and subsequent decay that characterizes all the years of a traveling life.

Amid all this, any who carry the traveler’s mantle seem wont to find the biggest such shockwaves and to sprint into them headlong — until the vagabond appears to be broken beyond his years. He has skipped middle-age, it seems; shirking his era of stolid, quiet endurance of sameness and duty known to more settled men. He bounces through so many towns and roadways with the infant’s naivete; he holds his head beneath bridges, contemplating death like a winnowed-down geezer facing Saint Peter’s gate. His flesh is only a mixture of the infant’s and the elder’s — his only possession of any freedom from the infirmities of either is found in his physically ‘rubbery’ form, which seems capable of taking a great deal of pointless abuse.

His great burden in life is only to ‘bring ruin to ruin,’ and to do so aimlessly. If the sculptor sculpts in marble and the painter paints in oil, the vagabond is the one whose art is made from his own flesh and heart. Stones on the earth dig into his spine like the sculptor’s chisel; blood on his knuckles after another scrap drips onto the soil like the painter’s paint. And where once such men were at a minimum constrained by the speed of their own feet, or of schooners and camels and horses; in the age of the machine — he now conducts his work at incredible speeds the likes of which would have driven his ancient wandering forefathers to certain madness. And verily, he is a madman.

For Emerson to write what he did in 1841 bodes poorly for our latter-day travelers. That then he could so straightforwardly conclude that travel is only conducive to the aging, dilapidation, and ruination of the traveler’s mind — well before the aeroplane and automobile were invented, and even before the locomotive came into common use — should roundly cause concern for any taken with traveling today. For today, travel is no less a process of “bringing ruin to ruin” as it ever was; the chief difference is, as Sir Wilfred Thesiger intones — that this process is sent into a sort of hyperdrive by the machines we now use to transport ourselves across vast distances at eyewatering speeds. Our travelers seem to be ‘bringing ruin to ruin’ as quickly as is humanly possible.

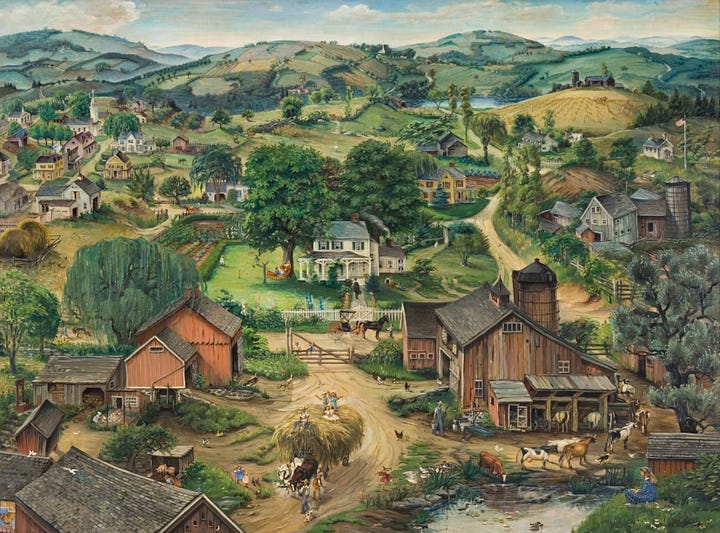

And yet, for this, the traveler’s resolve to achieve something by kicking his leaky boat off into the great unknown — or by wobbling his infantile form onto the high heights of the mattress on the floor to stand proudly — is, at heart, a natural instinct. Even the most exceptional homebodies in human history could not stay perfectly in place; even those taken with the strictest routinization of human life thrived not solely on routine, but in variation. The human heart craves any vista from which he can observe newness and change. One ‘travels’ even as they stay, on the whole, in place, as they forge through the eras of life and observe growth. To conceive, birth, and raise a child is to embark on a journey; to watch the seasons change and pass is itself an Odyssey — and at the end of it, I must wonder whether all of this business about what we’ve come to call travel is actually the aptest way to satisfy the urge that travelers often seek to quell.

In many ways, I have begun to suspect that ‘travel’ as we know it is only a juvenile and ill-formed realm of fantasy. Or, as Emerson presciently refered to travel an incredible 184 years ago, it is “a fool’s paradise” that even then held the fascination of well-heeled Americans. Perhaps some things never change — or perhaps, for some reason or other, our country is trapped in a sad, perverted sort of arrested development.

Just before his remarks on travel “bringing ruin to ruin,” in his essay Self Reliance, Emerson said this:

It is for want of self-culture that the superstition of Travelling, whose idols are Italy, England, Egypt, retains its fascination for all educated Americans. They who made England, Italy, or Greece venerable in the imagination did so by sticking fast where they were, like an axis of the earth. In manly hours, we feel that duty is our place. The soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still, and shall make men sensible by the expression of his countenance, that he goes the missionary of wisdom and virtue, and visits cities and men like a sovereign, and not like an interloper or a valet.

And so it goes that old Emerson was by no means one to cantankerously dismiss all human travel as a triviality or a liability to one’s sanity — to the contrary, here he affirms its value and occasional necessity. He even states quite boldly that the act of travel can bring virtue and wisdom to those of foreign lands. But what he outlines here is definitively not the sort of travel where one goes searching for some means to make themselves whole, nor could it be some kind of frivolous touristic lark. It is only when a man who happens to have changed his cartographical position moves as one who is already whole that his endeavors abroad can be remotely edifying. In going abroad from his own stead, a man must be “at home still” even as he goes. Barring this, his travels will only exponentiate whatever void he has in himself — and every mile will leave him exhausted, worse off, and ultimately ruined and defeated.

It is furthermore of great import here to emphasize his juxtaposition of Americans with the English, Italians, and Greeks. For they, in his estimation, “have no want of self-culture,” for they have already constructed it by “sticking fast where they are.”1

That the American nation was formed by people who quite often set out searching for something they lacked — looking for some impossible Eden, some world of wealth and fortune, et cetera — has, in some regard, trapped us in a fundamentally childish mythology. The mythos of the Mayflower, the wagon train, the hobo, and so forth remains inextricable from the American bloodline, and yet in our present condition, it cannot really be lived. Even if it could — it could not yield the fruits of virtue known in continental European civilization but in the most utterly exceptional circumstances.

We are a hopelessly restless people — even when settled. We pantomime the tranquility and peace of the classical Western cultures; buying a villa in Tucson, or a Victorian near Boston, or a Plantation House by Atlanta, we play-act as if we could ever actually remain there in a meaningful way. But it is all a strange and pitiful theatre in the great majority of cases; for the children of such families will doubtless move away to Austin, or Seattle, or, ironically enough — to Europe. And before one can even watch their olive trees bear fruit in their brick-facade, ‘Olive Garden’ style villa — they receive a job offer elsewhere, and pack the U-Haul with all the fever the pioneer ever packed his wagon train. We are, it seems, admixing the worst of nomadism and the worst of sedentary life; caught between two antipodes.

Our entire collective psyche is, therefore, one of boom and bust — that of a manic depressive. The interstate system is its physical expression; quite the same as the Cathedral at Rouen was ever an expression of the minds of medieval French Catholics — it is our art, our memory, our framework for thought and feeling. But where the Cathedral’s lifeblood is in the routine of its liturgies, the beauty of its buttresses and gardens, the gingerness of the good Priest; the Interstate is a morbid juxtaposition between cocaine-like high speed thrills — and bloody, mangled wrecks. All of the ‘in between’ on the American highway is only temporary.

Where our art takes on a more human form — one involving a good bit less concrete and asphalt — it is generally produced by those who are in the ecstatic throes of motion. The blues guitarist “stands at his crossroads,” the country singer was “thumbing toward Montgomery,” even the rocker is sleeplessly “driving to Brooklyn.” The ruination described by Emerson in 1844 is not solely exhaustion, it should be said. It is, prior to the dismal aging and defeat of the mind that such travels ultimately bring — utterly ecstatic, and even beautiful, if only for the briefest moment.

For this reason, stories of hoboes, traveling soldiers, sailors, cowboys, pioneers, and displaced poor folks captivate us. We crave such stories — but only at their ecstatic moments. When Kerouac drinks himself to death, or Elvis overdoses, or Marvin Gaye gets shot — we don’t ask why, we just turn up the music. And like the hopeless pervert who dreams of a life which is only one continual orgy (knowing full well that such a life would be impossible, or would ultimately only serve to darken him), we altogether seem to dream of life on the road to another boomtown, another honkytonk, another Edenic frontier, whistling as we go — forever. We dream this way even as we stay put, pantomiming a sham rootedness that will ultimately be disrupted by the surging craving for another ‘gold rush’. And so it is that we are, as Emerson noted all those generations ago, desperately feeling through the map as well as our own souls “for want of self-culture.”

Is a ‘settled’ culture even possible in America, then? Are we the sort who can even be ‘rooted in place?’ One wonders — and on this, I have no broad-scaled answer. I only know that love and lust differ chiefly in speed and discipline; that where the womanizer ‘takes the interstate’ to his destination — the suitor finds that if he is near his beloved, he is already there. The whore and the John race to the fetid room of the Howard Johnson for another ‘gold rush’ — while the two entangled in a wholesome courtship see real, timeless gold in one another, fully clothed. If one aspires to find some semblance of rootedness here in the United States, and to behold it as a jewel — even when he sets out abroad, as a whole and complete ambassador of his small place and all its beauties — it appears he must shun our ‘need for speed’ entirely. He must root himself completely on a scale that his heart can comprehend, and it is doubtful that this could take place on a scale much larger than a few acres.

These are the true things of maturation in the human mind and heart: The baby who has crawled atop the mattress, wide-eyed, never recognizing that mom and dad are so near — will soon develop the ‘object permanence’ required to climb greater mountains, and to take a fall without wailing in fear. She will develop the capacity for reason, and may find that the best sort of reason is borne of focus and stillness, the sort one finds only on the slow path. The simplest way to evade these realizations, if one wishes, is to remain ensconced in a state of total speed — for speed protects a man as he is, and shields his heart from all self-reflection that could allow him to identify his worries and shortcomings, and to fulfill them and make them whole.

Barring this, the human mind lives only in a world of images — and as he views the image, it is his whole world. The picture of the Hard Rock Cafe and the hot-tub suite; the video of the bawdy naked women; the picture out his windshield as he travels eighty-miles-an-hour down I-95; the picture of the parties at Ibiza, or Miami, or Manhattan. All of it like heroin, Twinkies, Superbowl touchdowns, Bacardi 151 — another U-Haul, another television show, another subdivision. And if at any point it is too exhausting to bear — a trip to Venice, to see what life could’ve been like; but even this image cannot last in the man whose object permanence is so handicapped. In the end, all of these images cling to his skin like armor, that his own ruin might be preserved — for it will be, in the end, the only thing that can be counted as being authentically his own.

These reflections come as we try to Fall Back in Love with America, and perhaps for good reason. After all, I cannot approach the subject of my country from any position of moral superiority, nor as an alien or interloper might. I am what I am describing: I spent the formative era of my adult life on the Interstate, and all of its discontents have left their scars. A high-speed life; bringing ruin to ruin — ugly nights amid brawling vagrants, harems of Jezebels burned into wretched memory, heat-lamp roller hot dogs at truck stops; and a constant need to move, manically, as a desperado moves, through every conceivable ideology, as if in a fever. None of it was happenstance; it was all a clinging action that mirrors the manner in which the infant clings to father after taking a hard fall, except in my case, the father was only the road.

All of it, armor, fortification, that I might hold onto the one place that I could truly call my own: My own private America; a frontier of primordial fear, a vacancy — a placeless quest for an impossible Eden. Never did it come — but of course, it was there from the start. I only ever needed the courage to begin — to accept my inheritance, and to stake out my earnest acre, to earn the wholeness of my own humanity by accepting the village culture of Western Civilization as the pinnacle of life’s purpose, over and against the squalid encampments of the roving frontier. I needed not to travel indefinitely, nor to fall back in love with America — I needed to accept that Upstate New York is my permanent home.

The story of these tensions and incongruities is, in many respects, the defining theme of our story as a nation. On one side — God the Father, Western Civilization, what with Cathedral bells and cobblestone village streets and great hanging gardens. On the other — the leaking sodhouse, the fresh-skinned possum, the running-with-a-gun delirium of the frontier. We mirror them together, though they cannot be spun into a single strand; we oscillate between them endlessly, carrying ruin to ruin in an exhausting and endless game of conflicting drives of the spirit.

That our national character appears to be fraught with incongruous impulses is in no way singular or exceptional — one finds analogues in nearly every country, people, and ethnic group on earth. Our contradictions are only singular in the respect that they are so extreme; to adopt one mode of the two I’ve described here would seem to require the abolition of the other, for they cannot coexist. We are as much Cain as we are Abel — and the endless broiling conflict between these two hemispheres of the American spirit seems to have produced as much politico-economic dominance as it has misery. There seems to be, after all, a great deal of money in ‘traveling away from oneself’ — evidenced not only by our collective wandering away from the ‘shire’ model of old Europe, but by the individual choice of any tradesman or white-collar professional to set out from his hometown in search of higher wages, double overtime, and lucrative gigs. Where rootedness was once a necessity — it is now a luxury with a steep ‘opportunity cost.’

Yet maturity comes in laying conflict to rest. It comes in the acceptance of the basic structure of virtue, and of the rhythm and shape of heavenly things, and from them, deriving the principles that govern life, beauty, and decency. The land and the life within it blossoms only by divine principle — holy laws of cell division and physics, of reproduction and cooperative advantage seem to permeate the entire landscape within which men live. A spruce tree only makes sense as a whole organism; an apple only comes in the fall. Rivers wear down massive sheets of bedrock, and on occasion, foxes starve to death. No doubt, a man aligned to these forces not only as their observer but as their steward stands to gain in his participation with them; and this participation cannot be cursory or occasional but must comprise the sum of his life on the land.

Even the town-dweller is not removed from it; he is every bit as much the produce of the landscape surrounding him as the country yeoman. Snowfall on the streets and heavy autumn rains correct his course; the change of the seasons governs his mind and intellect — and the condition of the country surrounding his town must be of some import to his business and mind. Both farmer and villager bring order to their respective spheres, piece by piece; a man derives meaning only from participation — and at that, participation not as free agent (as in the liberal conception of man) but as subject. The shape and structure of the virtues that govern him must indeed be organized in a fashion allowed and informed by his world; and in this respect, land begets a people, and people steward the land, and together, all of these dimensions cohere to create the spiritual and psychological reality of what it means to be a human being. This process is operative both within the local landscape and within the domain of timeless and universal virtue.

This is, insofar as I can tell, not only maturity — but civilization.

For citizenship and the classical liberal “individual” are at odds; The liberal is in some regard, if I can be frank — a baby. He lives in the world of the “me” and the “now” — the citizen, by contrast, lives not only in the world of the “we,” but in the world of the royal, virtuous “we, forever, with God.” He considers himself to be a corollary to a moral good which reaches beyond his own life, and for this reason, he is no utilitarian — he is not looking to maximize his own happiness at all. He is looking for the joy of forming a strong polity and a beautiful, edified people; he reaches for the filling meal of greatness as he strives to serve God almighty and His kingdom. And in this endeavor, he has only the wisdom of his forefathers, his sense of obligation to his civis, the life of prayer, and the beauty and clarity of the living land on which he lives as a guide.

His converse is the liberal — whose paltry ‘freedom’ includes freedom to spurn virtue, nature, God, and even to live life as a complete non sequitur of indulgence and illegibility. The classical liberal’s only sin is impeding, by his own action, the free intercourse of his compatriots — nothing more. His schema only works if virtue does not exist; if it is proven to be an antiquated superstition and little else. And where such proofs are lacking, well, it seems his habit is to imagine they do not exist, and failing this, he may stonewall the articulation of any virtue in the public sphere out and away from his world of ‘freedom.’

Travel is, for him, a thing done for the mere deviltry of it — and whatever iteration of travel inspires in him the greatest passion is the order of his day. Sublime, erotic, impossible fantasies of travel all stand at the forefront of his mind; an idyll without duty or encroachment upon the will of the flesh — a fling or a trust-fall on the alien world suffices to fulfill his craving for the exotic and fresh. Whether it is altogether conducive to his own edification or the common good of his own people is of no import whatsoever.

In many respects, such “travel” — or what in truth amounts only to simple tourism — only comes to comprise a pointless, vapid sacrament of individual liberty. For it has no roots in virtue; it contains no seed of civilizational greatness or contentment — it is simply a ticket to Emerson’s “fool’s paradise.”

"He called a little child to him, and placed the child among them. And he said: 'Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

Matthew 18:2-5

It may not be wrong to take something of a lesson from the climbing Canadian infant here — for as the Lord said, we are indeed to “become like the little children.” Perhaps she has shown us that the modus of travel can be employed to very good effect within a tight range of physical space; perhaps all that one seeks in an expensive voyage abroad is readily there to be found far closer at hand. One’s own back yard or home town — or indeed, the mattress on one’s living room floor — is only a bore if one has adopted a certain aloofness acquired in adulthood. And indeed, the origin of that aloofness is by no means objective, necessary, or absolute.

In fact, that aloofness is often downright pernicious and well outside the province of virtue. Modern, liberal society takes novelty as a sort of sacrament — and, it is not hard to find that those who seek novelty quite consistently find themselves mired in either perversion or acedia as they seek more and more exotic methods of obtaining a ‘fix’ for their cravings, or as they find themselves bored for having ‘seen it all.’ The chain-smoking existentialist, the opium eater, the Tik-Tok scroller, the booze-cruise tourist, and the ‘travel vlogger’ seem often enough to have a great deal in common — and none of it seems remotely congruent with an edifying, virtuous life. It is certainly incoherent insofar as the construction of great civilizations — the ones that might attract travelers for their beauty — is concerned.

As Emerson seems to conceive of it in Self Reliance, true sovereignty for a man — traveler or not — involves the quieting of every urge within himself toward novelty, toward speed, toward pulling up the tent stakes and running screaming across the void. Ideological fever dreams, gnawing paranoia, sensual cravings, hankerings for the exotic — aeroplanes and motorcars and highways, all an obstacle to the man who basks in the greatness of the organism of his world and society. Vagabond and tourist alike, perhaps if one cannot with certainty walk abroad as an abassador of their place, in definite terms, knowing themselves and their land and having a clear hand in their future, that they may bring some kind of wisdom to those they meet — then what business have they on the long road abroad?

Indeed, I ask myself this same question more and more.

Perhaps there is no Eden but the one we build; no breath of heaven but the one we see. And can one see anything as they race down the highway?

While one can imagine nomadic cultures who, as the settled members of European civilization, have no want of self-culture — these are exceptional societies who devote themselves entirely to a life of distinctively rooted transhumance, usually for the sake of shepherding various herd animals. Their ‘nomadism’ has nothing in common with that of the American jet-setter, or of the European on his August jaunt to Bali; to these, the rootedness of the Tuareg is alien and unknown. Barring a truly exemplary (and profoundly unlikely) experiment in creating some kind of tribal Western nomadism again, there is, quite likely, nothing to be gained by a life of constant rootlessness in any Western country — in spite of those who call themselves “gypsies,” “nomads,” and the like.

I have a friend who is fairly well traveled, at least compared to me. He has been to Europe, Asia, and South America, and has been to many cities in the USA. He 's traveled to some Balkan counties, and even made it to Istanbul and Cairo. He's definitely seen the elephant. I once asked him if there were any things he'd seen that, if he hadn't seen them, he thinks he would have really missed something. He said no. I was stunned by the answer. A lot of people who travel a lot go on and on about the wonders they've seen, and how they were transformed by the experience. My friend is a fairly insightful person, and also an honest one. He enjoys his travels, obviously, but he puts them in perspective. I wonder if more people, if they were being honest, would admit that the effect of their travels, however pleasant, do not provide the profound impact as the less glamourous, ordinary life of friends, family, and marriage and child raising in community. Of course, I've never seen the sunset in Bali, so what do I know?

Thanks for penning this Andy; you've articulated your thoughts wonderfully and given voice to much that has been on my mind. Hard to shake off the echo of Eliot's 'We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring. Will be to arrive where we started. And know the place for the first time.'