Three days ago, I awoke to find that we were out of bacon — which was a rude awakening indeed. To rise and to take my coffee; to read a few pages and watch the breezy morning rains lash against the windowpanes… these are the first stanzas of an old, reliable poem that must always end with a plate of eggs and bacon. This is simply how a morning must go in my house, for my wife and I are, in spite of our erratic and vagabond-ish biographies, quite earnestly creatures of habit. So, without so much as a thought, I donned my cap, jacket, and boots, and headed out the door, into the rain, to take the three-minute walk to the local store — to buy a pound of bacon.

At most grocery stores, one finds the bacon on a shelf, places it in a cart or basket, and totes it to the checkout themselves. Not so at our store. Here, the bacon is behind the counter, and customers must ask for it. So I leaned over the counter, offering a cheerful ‘good morning’ to the little old lady behind the register. I asked for a pound of her finest bacon, and while she was at it, how about a tin of my usual tobacco. She obliged with a smile, said “have a good day honey,” and in less than sixty seconds, I’d turned on my heel to head home. From the moment I’d realized our supply of bacon had run short to the moment two fresh slices were sizzling in the pan, not ten minutes had passed in all.

On the walk back home, I was struck with an unusual thought: where had I done this before? Exactly this — rising from bed, realizing that there is no more bacon, walking down the street, purchasing the same package of the same brand of bacon, even hearing the usual “have a good day honey!” from a silver-haired old woman — I’d done it all before, somewhere else. And to my memory, I’d done it all without riding in an automobile or placing an order on a smartphone, and had done it all in less than ten minutes… I began to wonder whether I was suffering a strange and potent case of early-morning amnesia.

“Oh, I remember now,” I thought. “I did that when I lived in New York City.”

This was a bizarre connection to make — for our village is, at least on its surface, a perfect antipode to New York City. It is almost a total absurdity that, as if by some ridiculous and even humorous cosmic glitch, these two localities could somehow be in the same state at all. It is a seven-hour drive from one to the other; and where the Big Apple’s streets bustle with activity and vibrant street scenes — our streets are derelict, dusty, and often totally empty. The air here smells of woodsmoke, spruce needles, and two-stroke chainsaw engines. ATV’s buzz by; camouflage-clad men hang bloody beaver skins in their yards to dry.

And where the Brooklyn ‘bodega’ stocks blunt-wraps and Hot Takis; our gas station stocks Copenhagen Long Cut, Little Debbies, and Labatt Blue. There is no rap music here, no Punjabi pop songs — only country radio — and where the walls of a Manhattan corner stores might be covered with bongs and Shen-Yun posters and Mexican flags, the walls of our little store are decorated with at least a dozen mounted deer heads and paper flyers for this year’s “RUN WHAT U BRUNG” springtime snowmobile dirt race. Suffice it to say that if my little village has anything at all in common with that vast metropolis that so rudely eclipses the vast State for which it was named — it certainly isn’t obvious at first blush. We are a long way from that city in more ways than one.

Yet, each time I go to the gas station now, I can’t help but see a deeper truth buried below the litany of differences that separate New York City from here. For the simple fact is — this village of ours is a prime example of ‘walkable, dense urbanism.’ Our streets are built for human use; there are sidewalks and stoops, taverns and apartments, parks, benches, gazebos, porches, and offices. We have a bank, a library, a laughably tiny medical center, a school, a beach, and several Churches. And if any of the 250 residents here should find the stock of the gas station to be lackluster, we even have another store in town. To visit all of the amenities and locations I’ve listed here would only require a fifteen-minute walk at the very most — I guess we are, quite unexpectedly, living in what some people are now calling a fifteen-minute-city (?)1.

Because of this, if I should wish to go to the pub — I simply shamble over there for a pint. If I need a book on Interlibrary Loan, I walk over to the library. Beer, wine, hot poutine, pizza, ice cream, onions, butter — I walk (or ride my bicycle) over to the store. We almost never leave the village, and in spite of living in one of the most rural areas of the American Northeast, driving and riding in automobiles is simply not something we do with any regularity whatsoever.

Moreover — and somewhat amazingly — we even have public transportation. Yes, it is infrequent; yes, the bus driver occasionally forgets to pick you up. Our system is, by all I can gather, a little like transportation systems in countries like Mexico and Greece… vague, languorous, devil-may-care. The schedule is imprecise, and to use the bus, you must call the dispatch center during business hours a full day ahead. Call on shorter notice and they might let you ride anyway, or they might just as well say you can ride but then fail to pick you up. Nonetheless, there is a tiny bus that will take you door to door from anywhere in this village to anywhere in the County Seat (population ~5,000), and as rural communities go, this is a rare blessing. Indeed, this raggamuffin transit system of ours has spared us from having to buy, maintain, and drive an automobile — and the savings because of this are nothing short of immense.

Weirdly, we find ourselves living an essentially urban lifestyle here. There may be only 250 residents in our village; we may be more than 100 miles to the nearest town with a population over 50,000, and more than 25 miles to the nearest village of 5,000 people. Nevertheless, we’re pulling off a rare iteration of hinterlands urbanism here, up in our ‘tiny city in the wilderness.’

In fact — our life here has more in common with a globally and historically normative definition of ‘urban life’ across the history of urban civilization. But, in our blind sprint into the world of the modern mega-city, this way of life seems to have been largely forgotten.

From this point of view, conventional wisdom on what does and does not constitute an ‘urban area’ begins to seem a little strange — if not outright inadequate. The definition the US Census Bureau uses to define an “urban area” feels arbitrary and flat: “…densely developed territory… encompass[ing] residential, commercial, and other non-residential land uses… with at least 5,000 people or at least 2,000 housing units.” It seems perplexingly incomplete. And a lot of historical, sociological, and urban planning textbooks offer little in the way of real insight on the matter, too. FHA’s “concentration of human structures…” seems as though it could include a commune or a family compound, and Natural Resources Canada’s “lack of agricultural activity” seems obtuse in areas where logging, mining, and timberland prevail (as is the case in much of Canada). More than any of these seemingly incomplete definitions, however, it simply seems that, in spite of all the grandiosities spoken about urbanization — we just haven’t really thought a whole hell of a lot about what a city actually is. The concept has changed so quickly, we can’t seem to keep track of it.

To make matters more confounding still, Plato’s ideal “city” would’ve had only 5,040 residents; but in states like New York, we have “cities” with less than 3,000 residents (like Sherill, NY) and “villages” with over 50,000 (like Hempstead, NY). Our definitions seem to be out of whack. Perhaps this is the product of a period of frenzied and feverish urbanization: For example, both Paris and New York City didn’t hit 1,000,000 residents until around ~1840, and for the first five centuries of Berlin’s history, there were less than 20,000 inhabitants there. Even London had, in spite of being the largest city on earth in 1840, only 2,000,000 people at the time — a paltry sum compared with today’s megacities, like Tokyo at 37,400,000. It seems that the long-standing, 10,000-year norms for how “cities” ought to be defined has changed so rapidly that at this stage, the definition of an urban area might as well be: “you’ll know it when you see it.”

In some regard, this actually may be the case. Because I propose that there are, at this stage, no absolute numerical guidelines for how an urban area can be defined. The core feature of what defines an urban area is, as I understand it, a question of relevance more than anything else. As any connoisseur of American cities can affirm, there are plenty of “hinterlands” in urban areas. From Sandtown in Baltimore to 98% of Kansas City and Little Rock, to weird backwaters in Staten Island and Troy and Cincinnati — there are a great many bona fide urban areas that evade the all-important gaze of the urbanite. One could say, I suppose, that these areas are technically ‘urban,’ but not intuitively ‘urbane’. And so these regions are awarded all of the same scorn that has ever been heaped upon rural hinterlands, villages, and hamlets across the United States, even if the exact dosage and flavor of this scorn may vary considerably.

Indeed, in the era of the techno-capital-driven megacity, and at a time when provincials the world over are falling over each other to pack into the largest cities they can conceivably move to — it is relevance that drives growth. Or at least, it is the perception of relevance that garners a populated area the kind of vibrance, dynamism, and attention that turns it from a squalid backwater into a properly ‘metropolitan’ locale. After all, there are cities that can be mentioned conversationally among well-to-do people in Manhattan, and there are cities that, if mentioned in the same environs, would be chuckled over, smirked at, and dismissed as hickish and obscure. It is that distinction, as trivial as it may seem, that may matter more than anything else on the question of what does and does not make a place ‘urban’. It’s essence is, for lack of a clearer, less-fickle term, relevance.

But — relevance to what, exactly? This is a tricky question to answer, because often enough, the relevance that makes the heart of truly metropolitan areas pump is entirely self-referential. There is, more often than not, no real “core” beneath the sky-high rents, and I say this because commerce and geography are increasingly divorced from one another. Where once it made sense for a merchant to reside in Manhattan, so as to be near the wharves where ships bearing valuable goods came and went — now, our latter-day counterparts to the merchants of old could just as well live in Greenland or Timbuktu, providing that they have a reliable internet connection.

In so many cases, great world cities emerged because of clear, absolute geographical advantages — but now, those advantages seem alien, forgotten, or even random, as they’ve been outmoded by a globalized economy that trades primarily in information. And likewise, where the ‘relevance’ that has often been the lifeblood of urban areas once meant direct proximity to commercial activity, and at that, proximity to the forms of commercial activity that are best facilitated by a city’s local geography — now, the process by which relevance is conferred onto an urban area is far more abstract, vague, and essentially ‘psychological’ in nature.

In other words, a larger and larger share of the economically productive activities that now take place in the world’s great metropoles could just as well take place anywhere. They could be — at least theoretically — dispersed entirely, or moved to the likes of places as “irrelevant” as Fort Dodge, Iowa or Madawaska, Maine, as the great bulk of internet-based jobs have no absolute need to be tied to any physical locations, factories, ports, granaries, and so on. In a sense, then, a large part of what is presently driving urbanization are the corporate policies consolidating personnel at face-to-face offices. The decisions underlying such policies are wholly private, and subject to change. What lay beneath those decisions seems to at least partially be a “psychology of relevance” — a feeling that people get when they move to a place that they are, for whatever reason, convinced is an important place.

Perhaps this is a more post-modern, formless iteration of the old, timeless, classical “feeling of being a part of something larger than yourself” that once drove people to join armies and Churches and to volunteer; perhaps it is even some of what once led many men to Pledge Allegiance to the Flag with great solemnity and gusto. Except, where each of these examples has an express structure and purpose defining the “something larger” in which the soldier, layman, citizen, or volunteer participates — the contemporary metropole has no explicit ‘end’ baked into it. It is instead simply a sense; a certain ‘busy-ness,’ or ‘vibrance,’ or a vague and largely un-defined sense of ‘diversity.’ The modern, internet-era ‘urban’ area is a place where “things are happening” — though whatever those “things” might be is essentially up to the individual urbanite.

In this respect, contemporary metropolitan areas are force multipliers for whatever version of one’s individual ‘self’ they may wish to cultivate, even if that version is disordered, contrived, or dishonest. The city is, for them, a sort of projector screen that amplifies the self into something larger than life — it is a method for turning an idealized version of the self into something “larger than the self.” This changeable, individualized, participatory schema has proven to be, at least on its surface, a psychologically suitable replacement for the old psycho-sociological bulwarks of former days; it is a ‘nationalism of one’ — a religion of the self, and the ‘shape’ of the modern metropolis appears to be the sole conduit through which it can flow.

The net result has been one vast, throbbing, expensive cacophony of atomized individualities, striving for social capital in an “IRL” iteration of the digital ‘attention economy’ — and access to this economy seems to command higher and higher rents.

In this environment, both the stated goals self-identified “urbanists” and the simple modus of old-school city folk often seem quaint or antiquated. To simply desire an affordable, walkable, dense urban environment — a familiar, normal, human ‘city of ten-thousand villages,’ and so on — is a far earthier, more romantical view of what the city is and could be than the modern ‘city of relevance’ that has been brought into being by the digital economy. Moreover, these views do not necessarily compute with many modern residents of urban areas; as these ideas are conceptually reliant upon networks of shared meaning-making systems and ideas — the sorts of philosophical artifices that could serve as obstructions on the long and fickle road to ‘relevance’ and the vague sort of ‘self-actualization’ that is now so popular in the collective ‘new urban’ subconscious.

What we are left with in all of this very chaotic calculus, then, is a quiet and gaping divergence in the contemporary urban public. A clear divide between more ‘old-order’ expressions of urbanity and a novel, formless, ill-defined ‘new urbanism’ that only sees the physical architecture of a city as a vector for the psychological thrill of ‘relevance’ in an ‘important place.’ This divide is extremely palpable in certain parts of Brooklyn, for example — where, in Park Slope, the latter type of urbanism is so obviously present, and in Brighton Beach and other, more working class neighborhoods, the former, less self-involved ‘flavor’ of urbanism is clearly native and predominant.

Interestingly, just as rural localities seem to have been ‘gobbled up’ by both the demographical trend toward urbanism and by a city-driven technological economy — the ‘old order urbanites’ are similarly disposable in cases where the ‘new urbanites’ see it fit to dispose of them. This is, in at least some dimension, the story of gentrification. And in that story, urban ‘hinterlanders’ and their rural counterparts are quite often molested by the very same economic and cultural forces — forces that are wielded by ‘relevant,’ moneyed, and urbane metropolitans.

So it goes that my village gas station and a Staten Islander’s bodega are not merely similar in form, but are also — unexpectedly — quite similar in their substance, too. Both are simple, ancient, un-prententious expressions of a timeless urban mode; each is a core element in a local, human-centered, urban culture that has no need of validation from the more ‘relevant’ portions of our modern metropoles. Presently, both of them are often enough in positions of identical precarity, too — and at day’s end, both of them seem to me to be unequivocally urban, at least by historically normative definitions of the word.

Of course as I write this, I realize that I am so completely out of my depth that this strange polemic I’ve penned here may even cause offense to the reader. It is almost ridiculous for a man like myself to engage in lengthy, speculative, psychoanalytical discourse on the spiritual condition of modern-day urbanites — for in all truth, I am not very deeply familiar with them or their world, and more than this, I write this essay from my desk in a tiny, obscure, isolated village. My brief stints in large cities (New York City and New Orleans) took place under the auspices of military service and nothing more; and the military’s presence in such places is often quite tentative and distant. Moreover, these stints were both rather brief, and did not afford me a particularly thorough window into the minds and hearts of modern-day urbanites. And so, what I have written thus far is only a brief summary of how these cities appeared to me ‘from the outside looking in’ and nothing more — for I can in no way be considered an authority on the matter of ‘urban studies’ or cities in general.

Nonetheless, the inquiries my brief periods in these cities have provoked in me have been exceedingly stimulating for me to ponder — perhaps most chiefly because so many young people take it as a foregone conclusion that they must, at all costs, find a way to ‘make it’ in a relevant, hip, important kind of city. Yet, on the flip side of this equation, it is a fair question to ask after the sources of this ‘hipness’ and ‘relevance,’ and to search out cases where its fundamentally self-referential character has ever been interrupted by the genuine and novel production of culture.

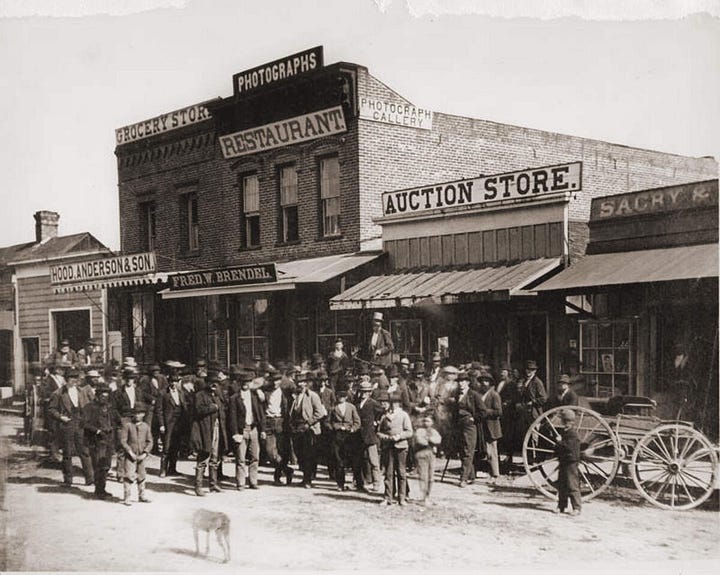

For after all, a brief look at the histories of Brooklyn, Oakland, Los Angeles, Chicago, Denver, and so on would quite clearly tell us that these cities were not born ‘cool’. The desirable statuses these cities now enjoy was not a foundational feature of any of these places in their early history; for indeed, each was extremely un-cool and completely irrelevant in their founding eras. Chicago was a doddering little village on an isolated frontier; Denver was a haggard collection of canvas tents and broken wagon wheels, and New York City was once a provincial collection of brandy-quaffing Dutch merchants and a passel of rustic yeomen and farmers. Indeed, I cannot find a single example of a city that was cool, relevant, hip, and universally desirable from its earliest dawning day. They were all eventually made this way — by people with an indomitable sense of style and a remarkable tolerance for risk.

These earliest settlers were either eccentric businessmen or their posse of vassals, servants, and henchmen; many were poor and scrofulous, living in dens of squalor or vice, chased out to the furthest-flung frontiers, all veritable refugees from the most ‘relevant’ quarters of their eras. Their refugee status may have come owing to criminal pasts, indentured servitude, slavery, or religious disputations, or in many cases, the grisly realities of economics, rents, and landownership back in the Old World. It was only much, much later that these ragged settlements would grow into the sorts of places about which respectable, bright young people would express any eagerness to move to; and whatever it was they were so eager to find in coming to these cities rested on and still rests squarely upon the backs of those cities’ irrelevant and often parochial forerunners.

What analogues to our great cities’ earliest days, then, exist today? Where are the locales where the castaways from our Manhattans and San Franciscos are absconding to by necessity — and if any such locales exist, what is being created there? What possibilities exist? Such questions would, by definition, take us straight to the hinterlands, be they urban, rural, or ‘micro-urban,’ as with our country’s villages and small towns.

On the first question, it seems to me that such people are more or less being cast to the four winds in a most unorganized fashion, as has often been the case when a society’s most desirable and relevant metropoles have been stifled by high rents and circular, self-referential cultural blights. Blacks from Harlem and Bushwick find themselves moving to Newark and Syracuse and Albany; broke artists and creatives priced out of the Mission and Uniontown and Bed-Stuy shamble off to foreign countries, or to cottage towns in Maine, or to low-rent districts of cities like Saint Louis and Detroit. More moneyed members of the class that, a decade ago, might’ve moved to the big cities are now descending upon the likes of Bozeman and Boulder and Burlington in full force — but these smaller markets become overburdened quickly, and rapidly ascend in price until they, too, are unaffordable to many seeking a semi-urban bastion of relevance and walkability.

But, on the question of what possibilities exist, I continually return to villages like my own and what they might represent. For — if it is now illegal to build the kind of ‘walkable, dense urbanism’ that exists in Manhattan’s Lower East Side (and verily, it is illegal to build now, owing to so many zoning laws, parking minimums, ADA requirements, and building codes), then it is natural that these areas would now be, in effect, “luxury housing products” commanding exorbitant rents that make such areas the exclusive purview of the international rich. But should it not also be natural that those seeking similar environs at more affordable rates would attempt to find what derelict, abandoned, inexpensive iterations of this kind of urbanism still exist elsewhere in the country?

On that score, America’s small rural villages seem to be capable of providing an answer, for they are at once classically urban, laughably affordable (with many homes priced well under $100,000), and their architectures and layouts are all grandfathered in, for they are vestiges of the pre-zoning, pre-ADA, pre-building-codes era. Moreover, because they are administered by far smaller polities than our largest cities, it is not hard to conceive of influencing their zoning boards and planning committees to adopt policies that would be favorable to the extension, improvement, and preservation of their ‘micro-urban’ character. So long as this question of “relevance” can be solved by those who choose to settle in places like these — it seems to me that they could serve to provide the ‘walkable, dense, affordable urbanism’ that so many young people appear to be so hungry for today.

To entertain such an idea, of course, a would-be cheapskate micro-urbanite would have to be pioneering and risk-tolerant; creative, thrifty, and comfortable with the idea of transgressing conventional wisdom on matters like jobs, crime, structural habitability, and distance from population centers. He would have to be willing to be the first one to try it — and would have to have a great deal of energy for the project of attracting others. He would have to have the guts and the gumption to buy a cheap house in a thoroughly irrelevant, far-flung village in America’s heartland. Those with sensibilities like these now stand to make incredible gains, and to potentially host a cultural Renaissance the likes of which this country has not seen in decades. The possibilities are, at this stage, nothing short of staggering.

It was not especially long ago that this exact idea came to fruition in America’s most blighted urban areas. To move to DUMBO in 1975 was considered deliriously insane — it was a crumbling, desolate nest of high crime, situated in a failing, bankrupt city, and possessed of no real redeeming qualities by the conventional standards of the time. Jobs were scarce; hazards were serious — but the rent was cheap, and so it was that a few hearty artists and creatives moved in, one by one, on the principle that cheap rent means more free time, and more free time means more time to devote to painting paintings, writing novels, reading, socializing, and engaging in all the requisite activities of artists, writers, thinkers, poets, musicians, and so forth. What followed was not only a creative Rennaisance that would profoundly impact American culture for generations, but a series of unlikely business opportunities that made many unsuspecting characters and eccentrics into millionaires.

All of this was the fruit of a simple penchant for risk, and a recognition that culture can be produced basically anywhere where the living is cheap. At that, it was a recognition that culture can be produced from scratch — all that is required is for a few adventurous souls to settle somewhere affordable and walkable, and to do so together. There does not seem to be any good reason why this could not happen today, especially when there are thousands of very affordable, walkable, dense villages in the United States today — villages like the one I grew up in, or the one that I now live in. For all the disgruntlement on the subject of sky-high rents in our biggest cities, one would think there would be a good many young people today searching for exactly this kind of alternative.

Then again, The Great American Gumption Shortage has ravaged the collective psyche of young Americans. The pioneering spirit that built America has been bled out of our citizenry, generation by generation, and the process has been so intensive that these days, anyone exhibiting that spirit seems to be considered highly eccentric — if not outright mad. Moreover, the median age crawls ever upward, not only as a simple fact of demographics but as a spiritual fact; our people — even our young people — are now mentally old. Nineteen-year-olds fret about “jobs” and “benefits” in a way that would’ve been considered ridiculous in ‘younger times,’ and men who’ve not yet seen the business side of their thirtieth year nibble their nails over their credit scores and blood pressure.

Sensible decision-making, of the sort employed by the middle-aged, is now the default even among the young — and so inasmuch as a given opportunity could require a measure of risk or a potentially unwise decision now, that opportunity will go untouched by youthful hands. Instead, foreign companies, private equity, immigrants, and developers make their moves — and native-born American youth who might’ve stood to profit from an investment in some strange and wonderful hinterland real estate go without.

Mesmerized by the tightly intertwined forces of relevance and sensible decision-making, they march off to the cities, where “the jobs are” — to doom-scroll on LinkedIn and to while away their hours sending off cover letters that go straight into the wastebin. Meanwhile, the rent comes due, the pressures mount, and all of this business about making sensible decisions in a relevant, important place begins to unravel these young people from the inside out. If they are doing it for any good purpose, it seems — at least judging by the online posts of such people — they do not seem to know what it could be.

If they succeed, of course, they may eventually crawl up into the sorts of jobs that offer them comfortable salaries and great benefits packages — and they will pine for vacations in the very hinterlands they spurned in their youth. They will find themselves in my town, in fact, and shall seat themselves at the bar here with a groan, admitting to the yokels beside them that they might’ve done better to move here from the very start. I have heard exactly such confessions as these from Manhattan lawyers, New Jersey city workers, union plumbers, and stock options analysts more than a few times — and I am convinced it has done no one any good; not them, not us, not America.

For this reason, when I write about “the hinterlands,” I am guilty of writing about them with a salvific tone — for I do genuinely believe that this country’s less-relevant, more obscure, generally ignored and overlooked backwaters are where the keys to our edification are buried. The bones of places like mine are not only capable of saving this country from it’s ghastly sprint into the world of ‘human resources’ and ‘economic development’ — they are also capable of saving individual Americans from disgruntlement and madness, if only they’ll take a chance in places like these.

Waltzing back home with my bacon in a grocery bag, watching the rain fall over the flags and buntings of my neighbors’ porches here in this village, realizing that this place is weirdly emblematic of the very ‘urbanism’ that so many renters now pay a premium for in our top-ten cities — it makes me wonder. What of this ‘relevance’ in our ‘important places?’ What of ‘jobs’ and security and ‘sensible’ decisions? Where are the men who do not seek out relevance as if it were something external from them — the men who generate relevance from their own implacable sense of style, urgency, hunger for risk, unorthodox approaches to ancient problems?

If such men do still exist, and they managed to find their way to a town like mine, why, we would have the very thing that so many are now seeking in our Brooklyns and San Franciscos and Austins and so on — we would have it in spades, here, and we would have it cheaply. It would be ours; we would own it, free and clear, sans the banks and the speculators — owned rightly and clearly for the inheritance of our children, and owned as a proving ground for seismic shifts in the broader culture that would have a generational impact. To produce culture and hipness and coolness — to make it rather than consuming it or rooting it out from the pits of our most vast metropolises: Is this not among the most laudable goals that a man could engage with today?

If it is — why am I here alone?

I am only being cheeky here. For those who don’t know, there are many populist-leaning types in America who are extremely leery of the World Economic Forum’s “ploy” to “corral everyone into fifteen-minute-cities,” as some kind of sinister effort to exert control over the populous. Whenever it’s discussed, there’s a subtext that basically amounts to “they’re gonna put you in there and never let you leave,” and it’s kind of a memetic corollary to “living in the pod” and “eating the bugs.” While this plan, if it actually exists in an actionable way, sounds like it sucks — it doesn’t appear that this ‘corraling’ effort is going to begin anytime soon. In the meantime, the idea seems to have boiled down to being a clever way to convince American populists to hate walkable dense urbanism and to regard it with scorn. Smells like a psyop to me.

My wife & I left the DC area and moved to northern Michigan in 1995. I am a retired hornist and piano technician. We used our DC area home equity to buy a house & shop on ten acres. Our son married a wonderful gal from Grand Rapids, and they now live in Ohio. We moved to a town a little more than an hour away from them. We are happy here, mainly because of the friendliness of Ohioans, plus our nearness to our son & his family. You can buy shoes, groceries, and all life’s necessities in town. I appreciate your thoughtful writing very much.

"Men did not love Rome because she was great. She was great because they had loved her."

G K Chesterton

There's definitely a difference between loving a city and a culture and merely just preferring to be there for convenience or opportunity. Loving requires commitment and sacrifice rather than just consuming and taking.